Okay, here is a 1200-word article focusing on the Zuni Pueblo reservation map in New Mexico, integrating history, identity, and suitable for a travel and educational blog.

>

The Living Map of Zuni Pueblo: A Journey Through Land, History, and Identity in New Mexico

The lines on a map are rarely just lines. For the Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico, the boundaries of their reservation, the contours of their mesas, and the course of their river etch a story far deeper than mere geography. It is a palimpsest of ancient migrations, colonial encounters, unwavering resilience, and a vibrant identity intrinsically tied to their ancestral lands. For anyone seeking to understand the true spirit of the American Southwest, a journey into the Zuni Pueblo’s living map is an essential exploration.

The Land Speaks: Unpacking the Zuni Pueblo Reservation Map

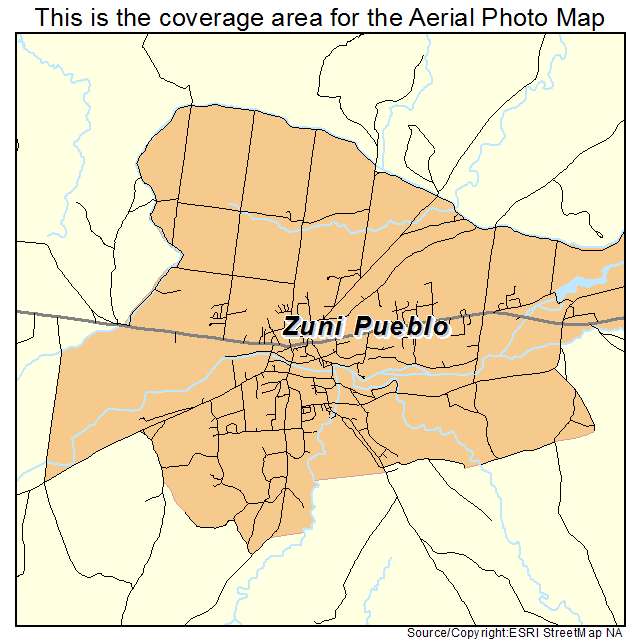

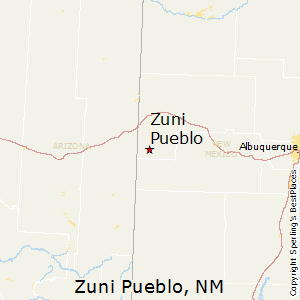

Located in west-central New Mexico, approximately 150 miles west of Albuquerque and 40 miles south of Gallup, the Zuni Pueblo Reservation encompasses over 700 square miles. At first glance, a modern map reveals a relatively compact, irregularly shaped landmass. But to the Zuni people, known as the A:shiwi, this is their Shiwanna, their sacred homeland, a universe in miniature.

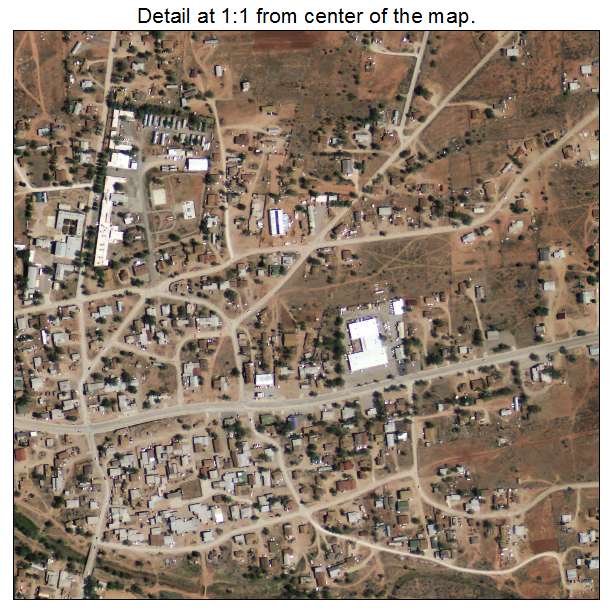

The dominant features on the map are the high desert mesas, dramatic sandstone cliffs, and the life-giving Zuni River, which winds through the heart of the reservation. This river, a tributary of the Little Colorado River, is more than just a waterway; it is a historical artery, sustaining generations of Zuni farmers and providing the clay essential for their world-renowned pottery. Prominent landmarks like Dowa Yalanne (Corn Mountain), a massive, flat-topped mesa towering over the main village, are not just geological features but sacred sites central to Zuni cosmology, serving as a refuge during times of conflict and a spiritual anchor to this day.

The current configuration of the reservation map is a stark reminder of a complex history. Unlike some reservations established by treaty or executive order in the 19th century, Zuni’s land base evolved from ancient occupation, Spanish land grants, and subsequent U.S. government recognition, often through a series of Executive Orders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These orders consolidated a fraction of their vast ancestral domain, lands that once stretched across significant portions of present-day Arizona and New Mexico, encompassing sites like El Morro (Inscription Rock) and the ancient ruins of Hawikku, one of the famed "Seven Cities of Cibola."

The map, therefore, doesn’t just show what they have, but silently testifies to what was lost. Yet, it also proudly displays what they retained and fought to reclaim. The Zuni have been proactive in land management and, through various legal and political efforts, have worked to recover and protect ancestral sites and resources both within and adjacent to their current boundaries, making the map a dynamic representation of ongoing stewardship and sovereignty.

A Tapestry of Time: Zuni History Woven into the Land

The history of the Zuni Pueblo is one of the longest continuous narratives in North America, stretching back thousands of years. Their story is not merely confined to textbooks; it’s etched into the very landscape visible on their map.

Ancient Origins and the Great Migration:

The Zuni trace their ancestry to the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi), who inhabited the Four Corners region. Archaeological evidence within and around the reservation points to human occupation for at least 3,000 to 4,000 years, with settled agricultural communities emerging around 700 AD. The Zuni oral traditions speak of a long migration from various cardinal directions, eventually converging at Halona Idiwana’a – the "Middle Place" – where the present-day Zuni Pueblo village is located. This journey, marked by ancient trails and seasonal camps, is a foundational element of their identity, each step mapped in their collective memory and spiritual narratives. The ruins of ancestral villages, scattered across the reservation and surrounding areas, serve as tangible markers of this deep past.

First Encounters and Spanish Colonialism (1540-1821):

The Zuni were the first Pueblo people to encounter Europeans. In 1540, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, lured by tales of the "Seven Cities of Cibola" (which were actually the Zuni villages), arrived at Hawikku, one of the Zuni towns. This encounter was violent, marking the beginning of centuries of struggle against colonial powers. The Spanish, seeking gold and souls, exerted immense pressure, introducing new diseases, livestock, and forced religious conversions. Missions were established, often atop or beside existing kivas (underground ceremonial chambers), symbolizing the attempt to overwrite Zuni spirituality.

Despite the imposition, the Zuni, like other Pueblo peoples, fiercely resisted. They participated prominently in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, a unified uprising that successfully expelled the Spanish for twelve years. Following the reconquest, the Zuni people consolidated their remaining villages into the single, defensible community around Dowa Yalanne, a strategic move visible on any historical map of the period, demonstrating their pragmatic adaptation and enduring spirit. The Spanish legacy, however, remains visible in elements of their architecture and the introduction of certain crops and animals.

Mexican and American Periods (1821-Present):

After Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, Zuni land claims largely remained unchanged. However, the arrival of the United States following the Mexican-American War in 1846 brought new challenges. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo promised to respect existing land rights, but American expansionism, the Gold Rush, and westward migration led to increased encroachment on Zuni lands. Non-Native settlers and ranchers began to stake claims, and the Zuni’s traditional land base shrank dramatically.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the establishment of the modern reservation system. While the Zuni Pueblo was recognized, the boundaries were significantly reduced from their ancestral domain. The federal government’s assimilation policies, including forced attendance at boarding schools and suppression of traditional religious practices, further threatened Zuni culture. Yet, the Zuni persisted. Their relative isolation helped them maintain their language (Shiwi’ma), unique ceremonial practices, and distinct artistic traditions.

The 20th and 21st centuries have been marked by a renewed focus on self-determination, cultural revitalization, and economic development. The Zuni have actively pursued land claims, managing their resources, and establishing tribal enterprises. The map today represents not just a land base, but a foundation for a sovereign nation actively shaping its future.

Identity Forged in Land and Time

The Zuni identity is inextricably linked to their land and its history. Every mesa, spring, and ancient ruin tells a story that reinforces who they are.

Language and Oral Tradition: The Shiwi’ma language, distinct from other Pueblo languages, is a cornerstone of Zuni identity. It carries the nuances of their worldview, their history, and their deep connection to the natural world. Oral traditions, passed down through generations, recount creation stories, migrations, and the significance of various landmarks visible on the reservation map, making the physical landscape a mnemonic device for cultural knowledge.

Religion and Spirituality: Zuni religion is a complex, profound system centered on maintaining harmony with the natural and spiritual worlds. Sacred sites like Dowa Yalanne, the various springs, and specific ceremonial grounds within the reservation are vital for their elaborate calendar of ceremonies, which include Shalako, a dramatic winter solstice event. The land provides the materials for their religious practices – corn for ceremonies, clays for effigies, and natural pigments. The cyclical nature of the land dictates the rhythms of their spiritual life.

Art and Craft: Zuni art is renowned worldwide, and its origins are deeply rooted in their environment. The distinctive Zuni pottery, with its intricate patterns and the use of natural clays found on the reservation, tells stories of their connection to the earth. Their elaborate silverwork, often inlaid with turquoise, shell, and jet, reflects the colors and elements of their high desert home. Zuni fetish carvings, depicting animals believed to possess spiritual power, are crafted from local stones, each piece embodying the spirit of the animal and the wisdom of the carver. These arts are not merely decorative; they are expressions of Zuni identity, cosmology, and economic self-sufficiency.

Community and Governance: The Zuni maintain a strong community structure, governed by an elected Tribal Council and a traditional religious leadership. Clan systems continue to play a role in social organization. The physical layout of the main village, with its multi-storied adobe buildings clustered around a central plaza, reflects centuries of communal living and shared responsibility. The map isn’t just external boundaries; it also illustrates the internal organization of a cohesive, self-governing people.

Visiting the Living Map: Education and Respectful Engagement

For the curious traveler or history enthusiast, visiting the Zuni Pueblo offers a unique opportunity to experience a living culture and understand the profound relationship between people and place. The Zuni Pueblo Cultural Arts & Visitor Center serves as an excellent starting point, providing context, history, and a chance to engage directly with Zuni artists.

When exploring the Zuni reservation, remember that you are on sovereign land, a home filled with sacred sites and active community life. Respectful tourism is paramount.

- Permits and Guidelines: Always check with the Visitor Center for current regulations regarding photography, access to specific areas, and any required permits. Many sacred sites are not open to the public, and their privacy must be honored.

- Support Local Artists: Purchasing authentic Zuni art directly from the artists or through tribal enterprises helps sustain their culture and economy.

- Engage with Openness: Attend public events or guided tours offered by the Pueblo to learn directly from Zuni people. Listen to their stories, which bring the lines on the map to life.

The map of the Zuni Pueblo Reservation is far more than a geographical outline. It is a testament to thousands of years of human habitation, a record of struggle and survival, and a vibrant declaration of an enduring identity. It invites us not just to see lines and landmarks, but to listen to the whispers of history, to feel the pulse of a living culture, and to understand the profound truth that for the Zuni, their land is not just where they live – it is who they are. To truly comprehend the Zuni Pueblo is to read their map, not with eyes, but with the heart.