Yellowstone: Beyond the Tourist Map – Navigating Ancient Indigenous Knowledge

To visit Yellowstone National Park is to stand at the precipice of geological wonder, a landscape that thrums with geothermal energy and echoes with the calls of elk and wolves. For millions, it’s a bucket-list destination, a testament to American conservation, and a place where nature reigns supreme. Yet, to truly experience Yellowstone, to scratch beneath the surface of its well-trodden trails and iconic geysers, requires more than a modern park map. It demands a journey into the rich, intricate cartography of the Indigenous peoples who knew this land as home for over 11,000 years – a mapping system far more profound than lines on paper.

Forget the notion of Yellowstone as an untouched wilderness "discovered" in the 19th century. This land was never empty. It was a vibrant, contested, and deeply understood territory for dozens of tribal nations, including the Crow, Shoshone, Blackfeet, Bannock, Nez Perce, and many others. Their "maps" were not static documents but living narratives, oral histories, astronomical observations, mnemonic devices, and an intimate understanding of the landscape itself. These weren’t just directions; they were encyclopedias of survival, spirituality, and sovereignty, weaving together resource locations, sacred sites, migration routes, and historical events.

Yellowstone as a Living Indigenous Atlas

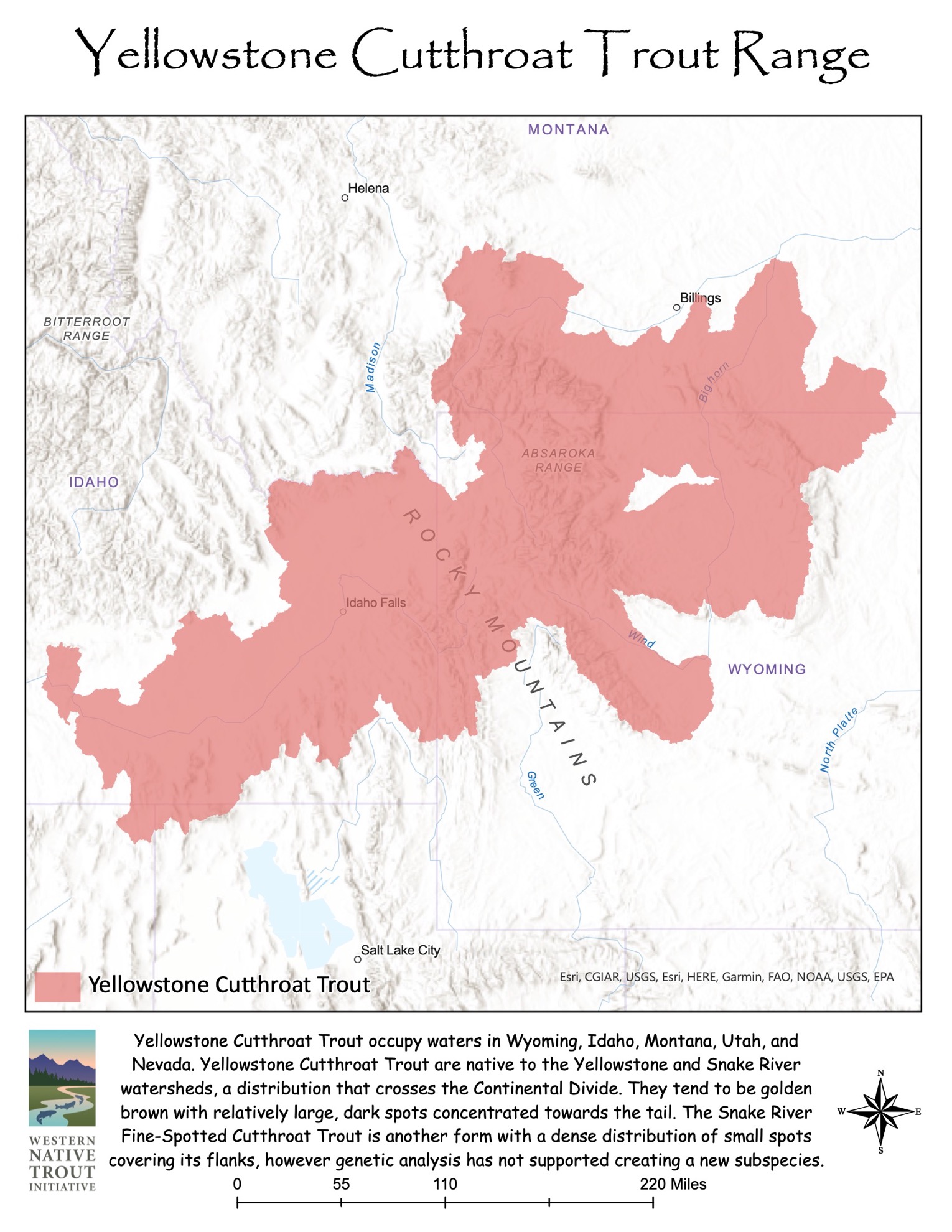

Imagine entering Yellowstone not with a fold-out map, but with a mind attuned to stories. The towering peaks of the Absaroka and Gallatin ranges become not just scenic backdrops, but ancient hunting grounds, vision quest sites, and defensive perimeters. The meandering Yellowstone River, from which the park ultimately derives its name (a translation of the Minnetaree name "Mi tsi a-da-zi," meaning Rock Yellow River), wasn’t merely a waterway; it was a highway, a source of life, and a boundary marker. Its vibrant yellow cliffs were prominent landmarks, embedded in tribal memory and lore.

Consider the geothermal features – the very essence of Yellowstone’s mystique. For early Euro-American explorers, these were curiosities, scientific anomalies. For Indigenous peoples, places like the Grand Prismatic Spring, Mammoth Hot Springs, or the mighty Old Faithful were often considered sacred, powerful, and sometimes dangerous. They were places for healing, for vision quests, for sourcing obsidian (a prized trade commodity), or for performing ceremonies. A Native American "map" would guide you to these sites not just by their physical location, but by their spiritual significance, their associated stories, and the protocols for approaching them. The steam rising from the ground wasn’t just steam; it was the breath of the Earth, a connection to the underworld.

The trails you hike today, often paved or well-maintained, frequently follow routes carved into the landscape by countless generations of Indigenous feet. The Bannock Trail, for instance, a historic route extending hundreds of miles, saw tribal groups traverse the park to hunt bison on the plains. To walk these paths is to walk in the footsteps of ancestors, understanding that the seemingly "wild" terrain was, in fact, a carefully managed and deeply known network of passages. These trails were not random; they connected water sources, camas meadows, fishing spots, and safe crossings, each junction a point of reference within a vast mental map.

Reading the Landscape: Beyond the Obvious

When you stand at the brink of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, gazing at the Lower Falls, the sheer power and beauty are undeniable. But an Indigenous perspective adds layers. This canyon was not just a geological marvel; it was a natural fortress, a source of minerals, and a challenging but navigable passage for those who understood its nuances. Stories would have detailed safe routes, dangerous currents, and the spirits that resided within its walls. The obsidian cliffs within the park were invaluable, providing superior cutting tools that were traded across vast distances, making Yellowstone a central hub in ancient economies. The location of these quarries was a key piece of information on any Indigenous "map."

Even the wildlife, so central to Yellowstone’s identity, was mapped in a way that transcended simple observation. Bison herds, elk migrations, and bear territories were not just points of interest; they were integral to survival. Native maps included detailed knowledge of seasonal movements, calving grounds, optimal hunting spots, and even the spiritual significance of each animal. A hunter’s mental map would include not just where the bison were, but when they would be there, how to approach them, and the rituals associated with a successful hunt. The very rhythm of life in Yellowstone was dictated by these deep understandings of the ecosystem.

The Erasure of a Legacy: A Cautionary Tale

The establishment of Yellowstone as the world’s first national park in 1872, while heralded as a triumph of conservation, came at a devastating cost to the Indigenous peoples who had stewarded the land for millennia. Their profound knowledge, their living maps, and their very presence were largely ignored, dismissed, or actively suppressed. The romanticized image of "wilderness" required the removal of its human inhabitants. Treaties were broken, tribes were forcibly removed, and their traditional ways of life in this region were shattered. The park, in its early iterations, became a symbol of a landscape "without people," a narrative that has only recently begun to be challenged and corrected.

This historical context is crucial, not to diminish the park’s natural beauty, but to enrich our understanding of it. By acknowledging the original cartographers and their deep connection to this place, we can begin to see Yellowstone through a wider, more respectful lens.

Re-Mapping Your Yellowstone Experience: A Call to Deeper Engagement

So, how can a modern traveler access these ancient maps and deepen their Yellowstone experience?

-

Educate Yourself Before You Go: Don’t rely solely on park brochures. Seek out books, articles, and documentaries that focus on the Indigenous history of Yellowstone. Look for resources from tribal nations themselves, where available. Understanding the stories before you arrive will prime your mind to see beyond the surface.

-

Visit Interpretive Centers with an Open Mind: While park exhibits have historically been limited in their Indigenous representation, many are slowly improving. Look for displays that discuss Native American history, tool-making, or land use. Ask rangers if there are specific programs or materials available that highlight Indigenous perspectives.

-

Hike Mindfully: As you walk the trails, remember you are likely on ancient pathways. Imagine the generations who traversed the same ground. Observe the plants and animals not just for their beauty, but for their role in a complex ecosystem that sustained human life for thousands of years. Consider the resources available along the path – water, shelter, food sources – and how they would have been "mapped" in an Indigenous context.

-

Look for Clues in the Landscape: While direct physical evidence like petroglyphs is rare and often protected or unmarked, the land itself tells a story. Look at the strategic placement of a mountain pass, the abundance of a particular plant, or the natural shelter offered by a rock formation. These were the "features" on Indigenous maps.

-

Challenge the "Wilderness" Narrative: Actively remind yourself that this was never an empty land. It was a cultural landscape, shaped by human interaction and deep knowledge. This perspective transforms a scenic drive into a journey through a living, historical archive.

The Transformative Power of Indigenous Cartography

To engage with the Indigenous maps of Yellowstone is to embark on a far richer, more profound journey than any conventional tourist experience can offer. It transforms the park from a collection of impressive natural wonders into a vibrant, living testament to human ingenuity, resilience, and spiritual connection to the Earth. It’s an invitation to see the land not just as scenery, but as a repository of stories, wisdom, and a history that stretches back to time immemorial.

By understanding that every geyser, every peak, every river bend had a name, a story, and a purpose within a vast, interconnected Indigenous world, we don’t just visit Yellowstone; we begin to truly know it, honoring the original guardians and cartographers of this extraordinary place. This deeper understanding is the ultimate souvenir, a new lens through which to view not just Yellowstone, but our own relationship with the landscapes we inhabit. It is a powerful reminder that the most valuable maps are not always those printed on paper, but those etched into the memory of a people and the very fabric of the land itself.