The Living Map: Unveiling Wisconsin’s Native American Nations

The map of Wisconsin’s Native American tribes is far more than a geographical outline of past and present territories; it is a dynamic tapestry woven with threads of deep history, resilient identity, and enduring sovereignty. For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this map means delving into millennia of human presence, profound cultural shifts, devastating challenges, and remarkable revitalization. This article explores the rich narrative embedded within Wisconsin’s Native landscape, from pre-colonial grandeur to the vibrant nations of today.

The Ancient Heartbeat: Pre-Colonial Wisconsin

Before European contact, the land now known as Wisconsin was a vibrant, interconnected network of diverse Indigenous nations, each with its unique language, governance, spiritual practices, and relationship to the environment. The region, rich in forests, lakes, rivers, and fertile lands, supported thriving communities that practiced sophisticated agriculture, hunting, fishing, and extensive trade.

Prominently inhabiting the area were:

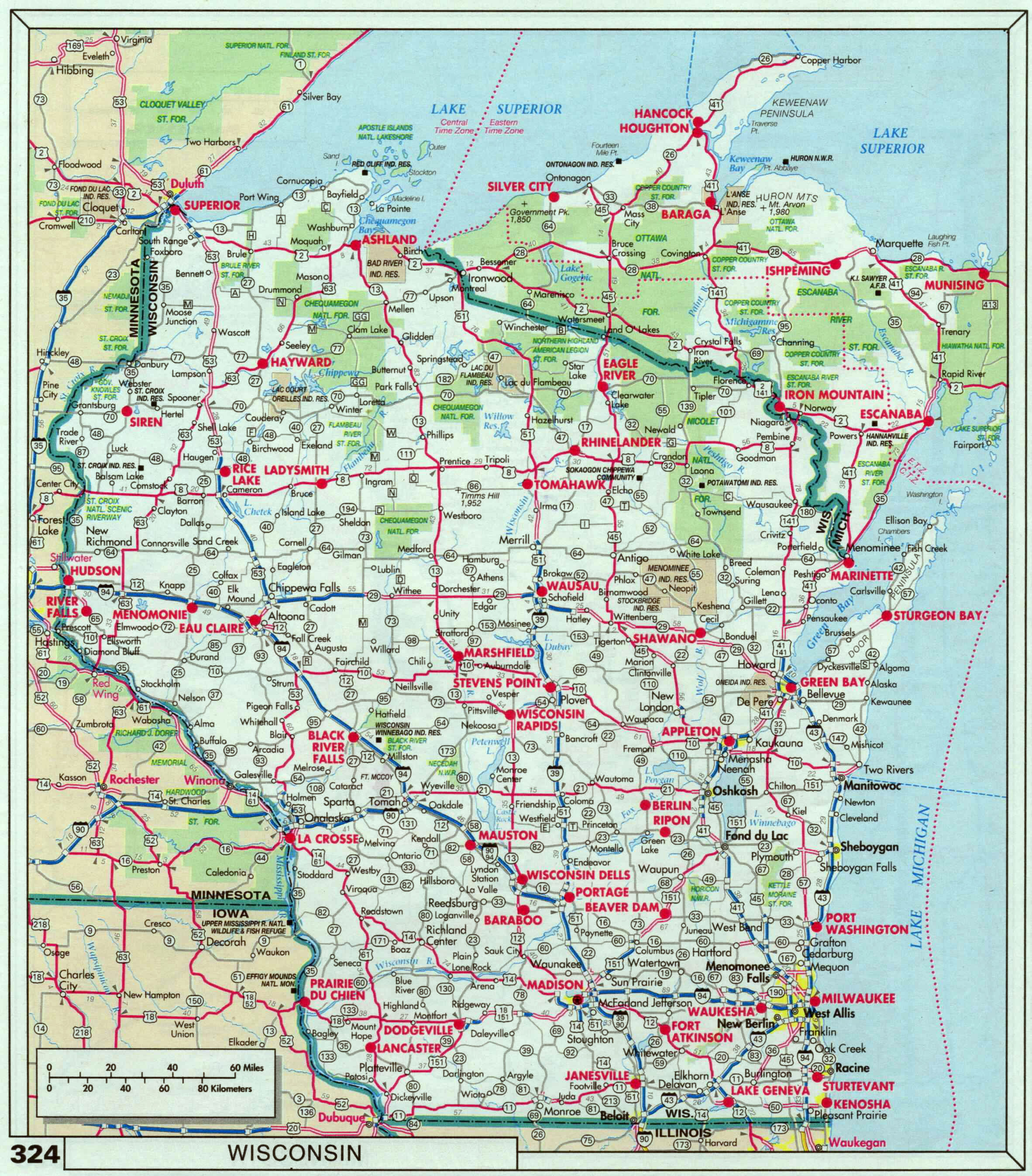

- The Ojibwe (Anishinaabe): Also known as Chippewa, they were a dominant presence across the northern reaches of Wisconsin, extending into Michigan, Minnesota, and Canada. As part of the larger Anishinaabe confederacy (which includes the Odawa and Potawatomi), they were skilled navigators of the Great Lakes, renowned for their birchbark canoes, wild rice harvesting, intricate beadwork, and strong spiritual connection to the land and water. Their history in Wisconsin stretches back centuries, migrating westward along the Great Lakes.

- The Menominee: Considered one of the oldest continuous residents of Wisconsin, their name, "Oma͞eqnomenēwak," means "People of the Wild Rice." Their ancestral lands encompassed vast areas of northeastern and central Wisconsin, a territory they meticulously stewarded. The Menominee possess a unique Algonquian language distinct from their neighbors, reflecting their deep roots and singular cultural evolution within the region. Their history is one of remarkable resilience, having maintained a significant portion of their ancestral forest.

- The Ho-Chunk (Winnebago): Speaking a Siouan language distinct from the surrounding Algonquian tribes, the Ho-Chunk people occupied central and southern Wisconsin for thousands of years. Their traditional territory included the fertile lands around Lake Winnebago and the Wisconsin River. Known for their intricate oral traditions, powerful clan systems, and strong sense of self-governance, the Ho-Chunk maintained a distinct cultural identity amidst their neighbors.

- The Potawatomi (Anishinaabe): Another branch of the Anishinaabe, the Potawatomi ("Keepers of the Fire") were traditionally located in southeastern Wisconsin, extending into Michigan and Illinois. They were skilled farmers and traders, playing a crucial role in regional alliances and trade networks.

These nations were not static entities but dynamic societies, engaged in complex relationships of trade, alliance, and sometimes conflict. Their boundaries were understood through shared knowledge, natural landmarks, and traditional usage, rather than rigid lines on a European-style map.

The Shifting Sands: European Contact and Colonial Impact

The arrival of European traders, missionaries, and eventually settlers in the 17th and 18th centuries irrevocably altered the Indigenous landscape of Wisconsin. The fur trade initially brought new goods and opportunities but also introduced devastating diseases, increased intertribal conflict fueled by competition for resources, and a growing dependence on European economies.

As American expansion intensified in the 19th century, the pressure for land became immense. A series of treaties, often coerced and poorly understood by Native leaders, systematically dispossessed tribes of their ancestral territories. These treaties, frequently violated by the U.S. government, led to massive land cessions and the forced removal of many communities to lands west of the Mississippi River or to smaller, designated reservations within Wisconsin.

This period saw the arrival of new Native American communities to Wisconsin, themselves displaced from their traditional homelands further east:

- The Oneida: Originally from New York, they were one of the "Six Nations" of the Iroquois Confederacy. Displaced by colonial expansion, a portion of the Oneida Nation relocated to Wisconsin in the 1820s, settling near Green Bay.

- The Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians: Descendants of various Algonquian-speaking peoples (Mohican and Lenape/Munsee) from the East Coast, they too were pushed westward, eventually establishing their community in Shawano County, Wisconsin.

- The Brothertown Indian Nation: A unique community formed from Christianized Native Americans from various New England tribes (including Narragansett, Mohegan, Montauk, and others), they also migrated to Wisconsin in the 1830s, settling in Calumet County. While they achieved federal recognition in the 1830s, it was later terminated and they are currently seeking re-recognition.

The map of Wisconsin transformed from a mosaic of traditional territories to a landscape dominated by rapidly expanding non-Native settlements, with shrinking islands of designated reservation lands.

The Modern Map: Sovereignty, Resilience, and Revival

Today, the map of Wisconsin reflects the enduring presence and sovereignty of eleven federally recognized Native American nations and one state-recognized nation. These communities, while occupying significantly smaller land bases than their ancestral territories, are vibrant centers of cultural preservation, economic development, and self-governance.

Each nation maintains a distinct identity and history:

- Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa: Located on the south shore of Lake Superior, they are stewards of critical wetlands and wild rice beds.

- Forest County Potawatomi Community: Having faced significant dispersal, this community returned to Wisconsin and has rebuilt a strong nation in northeastern Wisconsin.

- Ho-Chunk Nation: Despite intense pressure and multiple forced removals, the Ho-Chunk people fought tirelessly to remain in Wisconsin. Today, the Ho-Chunk Nation is unique in that its lands are scattered across several counties, acquired through land purchases, reflecting their resilience and refusal to be confined to a single reservation.

- Lac Courte Oreilles Band of Lake Superior Chippewa: Situated in northwestern Wisconsin, this nation is known for its strong cultural programs and efforts to preserve traditional practices.

- Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa: Located in Vilas County, they maintain deep connections to their extensive lakes and forests, central to their identity and economy.

- Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin: The Menominee hold a unique place, having retained a significant portion of their ancestral forest land. After a devastating period of federal "termination" in the 1950s that stripped them of their federal recognition and tribal status, they successfully fought for restoration in the 1970s, a testament to their unwavering spirit.

- Mole Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (Sokaogon Chippewa Community): A smaller but culturally rich community in Forest County, deeply connected to Rice Lake, a vital wild rice harvesting area.

- Oneida Nation: Located west of Green Bay, the Oneida Nation has grown into a major economic and cultural force, demonstrating remarkable development and self-sufficiency.

- Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa: Situated on the beautiful Bayfield Peninsula, this nation maintains strong ties to Lake Superior and its traditional fishing economy.

- St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin: With communities in both Wisconsin and Minnesota, they maintain cultural continuity across state lines.

- Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians: In Shawano County, they continue to preserve their unique East Coast heritage and language while thriving in Wisconsin.

- Brothertown Indian Nation: While not federally recognized at present, the Brothertown Indian Nation is recognized by the State of Wisconsin and is actively pursuing federal recognition, maintaining a strong community and identity in the state.

These nations operate as sovereign governments, exercising inherent rights to self-governance, managing their lands, establishing laws, and providing services to their citizens. The concept of sovereignty is central to understanding the modern Native American map – it signifies their status as distinct nations within the United States, not merely ethnic groups.

Identity Beyond Borders: Culture, Language, and Future

The map, therefore, is not just about land boundaries; it’s a living representation of cultural survival and identity. Each reservation or community is a vibrant hub where Indigenous languages are being revitalized, traditional ceremonies are practiced, storytelling thrives, and intergenerational knowledge is passed down.

For instance, the Menominee forest is not merely timber; it’s a testament to sustainable forestry practices passed down for generations, embodying their spiritual and physical connection to the land. The wild rice beds protected by the Ojibwe and Menominee are not just a food source; they are sacred elements of creation stories and a core component of cultural identity. The Ho-Chunk’s determination to remain in Wisconsin against all odds speaks volumes about their deep ancestral ties to the land.

In recent decades, economic development, often spearheaded by gaming revenues, has provided critical resources for tribal governments to invest in education, healthcare, housing, and cultural programs. This economic self-sufficiency further strengthens their sovereignty and ability to shape their own futures. Beyond gaming, many tribes are leaders in environmental stewardship, renewable energy, and cultural tourism, inviting visitors to learn about their heritage.

Engaging with the Living Map: For Travelers and Educators

For those interested in history, culture, and responsible travel, understanding Wisconsin’s Native American map offers invaluable opportunities:

- Visit Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums: Many nations operate museums and cultural centers that offer authentic perspectives on their history, art, and contemporary life. Examples include the Menominee Cultural Museum, the Oneida Nation Museum, and the Ho-Chunk Nation Museum and Cultural Center.

- Attend Public Events: Powwows, traditional ceremonies, and cultural festivals are often open to the public and provide immersive experiences into Indigenous cultures.

- Support Tribal Businesses: From gas stations and hotels to art galleries and restaurants, supporting tribal enterprises directly benefits the community.

- Acknowledge Land: Incorporate land acknowledgments into your educational or travel narratives, recognizing the Indigenous peoples who are the original and ongoing stewards of the land you are on.

- Learn Respectfully: Approach learning with an open mind and a willingness to listen. Challenge preconceived notions and seek out Indigenous voices and perspectives.

The map of Wisconsin’s Native American tribes is a powerful reminder that history is not static; it lives and breathes through the enduring presence of its original peoples. It tells a story of profound connection to the land, of resilience in the face of immense adversity, and of the unwavering determination to preserve unique identities and sovereign futures. To truly understand Wisconsin is to understand this living, evolving map and the vibrant nations it represents.