Unveiling the Great Salt Lake: Navigating Ancient Paths on Antelope Island

Forget your GPS for a moment. Close your eyes to the digital screen and open them to a landscape that speaks volumes, etched not by lines on paper but by millennia of human interaction, resource identification, and spiritual connection. The Great Salt Lake region, a vast and mesmerizing expanse, was not merely a blank space to its original inhabitants. For the Shoshone, Ute, Goshute, and Fremont peoples, it was a living map, a dynamic chart of survival, spirituality, and sustenance. To truly "review" this place, one must step beyond modern cartography and attempt to read the land as they did. There’s no better vantage point for this profound shift in perspective than Antelope Island State Park.

Antelope Island isn’t just a scenic drive or a wildlife haven; it’s a masterclass in indigenous cartography. From its highest peaks to its brine-lapped shores, every feature on this island and the surrounding lake held significance, forming a complex mental and oral map passed down through generations. Modern maps might show contours and roads, but Native American maps of this region were fluid, seasonal, and resource-driven. They highlighted freshwater springs, bison migration routes, prime fishing spots, obsidian sources, and ceremonial grounds. Visiting Antelope Island today, with this historical lens, transforms a simple trip into an immersive journey through time and understanding.

Antelope Island: A Crossroads of Knowledge

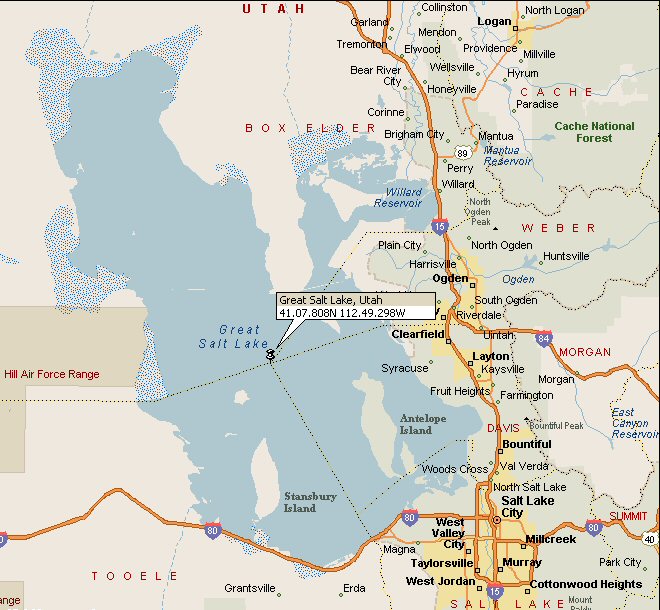

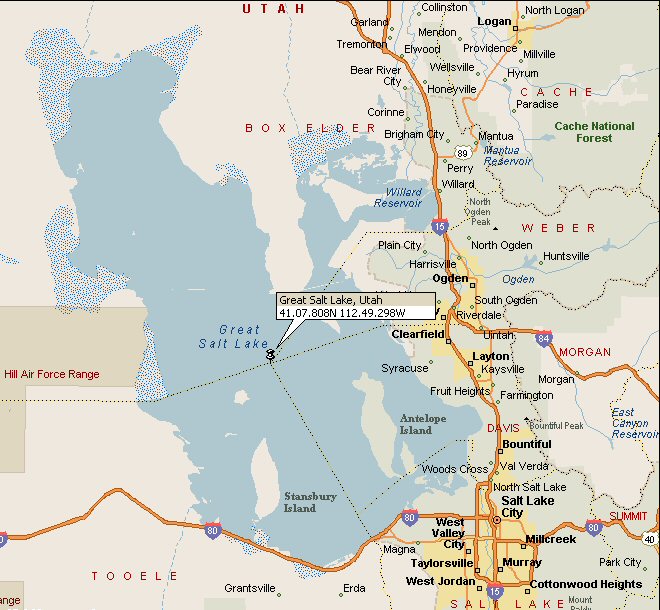

Rising majestically from the saline waters, Antelope Island (historically known as "Church Island" by some non-native explorers, but its indigenous names would have reflected its resources or spiritual significance) served as a vital landmark and resource hub. Its unique position in the middle of the lake made it a natural beacon, visible for miles from the surrounding mountain ranges – the Wasatch to the east, the Oquirrh to the south, and the Stansbury to the west. These peaks, too, were not just geological formations; they were integral parts of the regional map, offering directional cues and delineating tribal territories.

For the ancient mapmaker, the island’s topography would have been paramount. The long, north-south spine of the island, culminating in Frary Peak, offered an unparalleled panoramic view. From this summit, one could "read" the vastness of the lake, identify distant islands like Stansbury and Fremont, and trace the outlines of the surrounding mountain ranges. This high ground would have been crucial for spotting game, observing weather patterns, and identifying potential threats or incoming travelers. It was a natural watchtower, a strategic point from which to gather intel for the "map" of the day.

The island’s resources were its true treasures, dictating settlement patterns and travel routes. Prior to the lake’s current high levels, a land bridge often connected the island to the mainland, allowing easy access for hunting and foraging. The herds of bison that roam the island today are descendants of a introduced population, but buffalo were indeed present in the Great Basin, and their movements would have been central to indigenous "maps." Their presence meant sustenance, hides, and tools. Understanding their seasonal migrations – where they grazed, where they watered – was a critical layer of geographical knowledge. Similarly, the island’s freshwater springs, scarce but vital, would have been marked with absolute precision on any mental map, dictating rest stops and camping locations.

Beyond large game, the lake itself was a rich larder. Brine shrimp, a cornerstone of the lake’s ecosystem, attracted millions of migratory birds. Shorelines would have been mapped for prime bird hunting, egg gathering, and the collection of other lake-based resources. The vast salt flats to the north and west of the lake were also essential, providing salt for preservation and trade – another crucial feature for any indigenous "map" of commerce and survival.

"Mapping" Through Experience: The Living Landscape

Native American mapping was an embodiment of living with the land, not just looking at it. It was a holistic understanding rooted in observation, memory, and oral tradition. When you hike Frary Peak on Antelope Island, you’re not just gaining elevation; you’re tracing paths that were likely followed for millennia. As you ascend, pause and look back. Note the way the terrain slopes, the direction of the wind, the quality of the light. These were the fundamental data points for indigenous navigation.

From Frary Peak’s summit, the Great Salt Lake unfurls beneath you, appearing less like a static body of water and more like a dynamic, breathing entity. Imagine standing here, without a compass or a paper map, needing to convey to others where to find good hunting, safe passage, or a sacred grove. You would point to the distant mountains, describe the particular shape of a shoreline, reference a star constellation, or recount a story associated with a specific rock formation. These were the "legends" and "symbols" of their maps.

The island’s numerous coves and bays, like Buffalo Bay or White Rock Bay, would have been named for their characteristics or the resources found there. These names, often descriptive rather than arbitrary, served as mnemonic devices, encoding geographical information. "The place where the big fish jump," "the bay of sweet water," or "the ridge of flint" – these were the labels on their maps, far more informative than abstract place names.

Experiencing the Indigenous Map Today

To truly engage with the concept of Native American maps on Antelope Island, here’s how to approach your visit:

-

Hike Frary Peak: This is non-negotiable. The panoramic view (a moderate 6.6-mile round trip with 2,000 feet of elevation gain) is your primary tool for "reading" the landscape. From the top, try to identify the major mountain ranges: the Wasatch to the east (where the sun rises), the Oquirrhs to the south, and the Stansburys to the west. Visualize how these would have guided travelers. Imagine the vastness of the lake as a barrier and a highway.

-

Observe the Wildlife: Spend time watching the bison, antelope, and migratory birds. Consider their movements and how these would have informed historical routes. The presence of water and forage dictates animal movement, and understanding this was key to survival.

-

Explore the Shorelines: Walk along the sandy, salty beaches. Notice the unique ecosystem of brine shrimp and flies. This ecosystem, though sometimes pungent, was a critical food source for birds and, indirectly, for humans who hunted those birds.

-

Visit the Fielding Garr Ranch: While primarily a historic ranch from the pioneer era, it sits on one of the island’s most reliable freshwater springs. This spring was undoubtedly known and utilized by indigenous peoples for millennia before European settlement. Its consistent flow made it a prime location for encampments.

-

Stargaze: Antelope Island is a designated International Dark Sky Park. At night, the stars become another layer of the ancient map. Indigenous peoples used celestial bodies for navigation, marking seasons, and spiritual understanding. Looking up, you connect with a timeless way of understanding direction and time.

Beyond the Island: The Greater Great Salt Lake Basin

Antelope Island is a microcosm of the larger Great Salt Lake basin. The entire region, from the wetlands of Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge in the north to the desert expanses of the Bonneville Salt Flats in the west, was interconnected by a network of indigenous knowledge. The lake itself, varying dramatically in size and depth over centuries, influenced everything. At times, its lower levels revealed vast mudflats, creating new routes and exposing resources. At higher levels, it became a formidable barrier, necessitating long detours or the development of rudimentary watercraft.

The rivers feeding the lake – the Bear, Weber, and Jordan – were arteries of life, their banks serving as natural highways and their waters providing essential freshwater. The fertile deltas where these rivers met the lake were prime locations for gathering plant foods and hunting. These riverine corridors were as important to the indigenous "map" as the major mountain passes.

A Call to Mindful Exploration

Reviewing Antelope Island and the Great Salt Lake region through the lens of Native American maps is not just an academic exercise; it’s a transformative travel experience. It forces you to slow down, observe, and connect with the land on a deeper, more intuitive level. It highlights the incredible ingenuity, profound knowledge, and enduring spirit of the peoples who called this place home for thousands of years.

As you plan your trip, pack your hiking boots, plenty of water, and an open mind. Leave your modern maps in your pocket occasionally and try to "read" the landscape yourself. Look for the natural indicators, imagine the resources that sustained life, and listen for the echoes of stories told around ancient campfires. Antelope Island isn’t just a place to visit; it’s an invitation to understand, to honor, and to rediscover a way of seeing the world that is as ancient as the lake itself. It’s a profound reminder that the most detailed maps are often those etched in the heart and mind, passed down through generations who truly knew their home.