Unmapping Tragedy: A Journey to Sand Creek and the Echoes of Cheyenne Ancestral Lands

The concept of "historical range maps" often conjures static lines on paper, delineating territories of past peoples. For the Cheyenne Nation, these maps represent not just geographic boundaries, but a living tapestry of culture, nomadic lifeways, and a tragic history of displacement. To truly understand the weight and meaning behind these cartographic representations, one must visit the landscapes they define—or, in the case of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, the precise point where those expansive ranges were violently and irrevocably challenged. This is not a typical travel review; it’s an invitation to confront history, to walk on ground soaked in memory, and to grasp the profound human cost behind the lines on a map.

The journey to Sand Creek is, by necessity, a pilgrimage. Located in southeastern Colorado, far from bustling interstates and major cities, the site demands effort to reach. The drive itself becomes part of the experience: endless high plains stretching to the horizon, a landscape that whispers of buffalo herds and tipi villages that once dotted this vast expanse. This is the heart of what historical maps label "Cheyenne territory"—a vast, unsegmented space of opportunity and sustenance, crisscrossed by hunting trails and seasonal migrations. As the pavement gives way to gravel, and the GPS directs you further into the quiet solitude, you begin to shed the distractions of the modern world, preparing for a confrontation with the past.

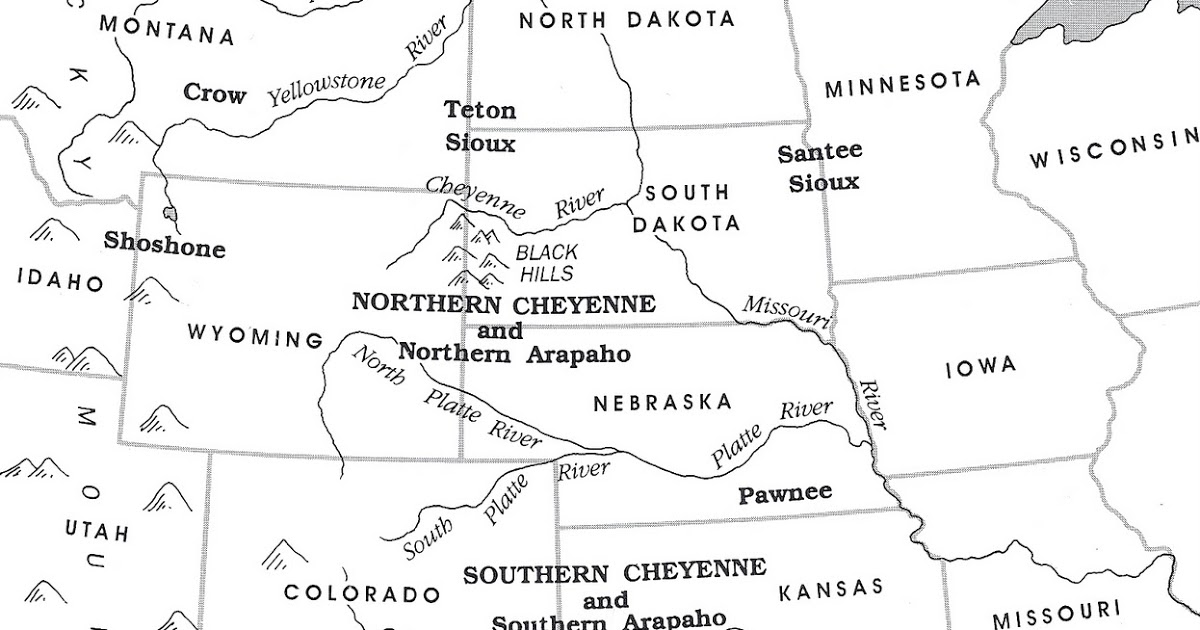

Upon arrival, the first impression is one of stark, profound quiet. The visitor contact station is modest, respectful, and designed to prepare you for what lies ahead. There are no grand monuments or elaborate structures, but rather a thoughtful collection of interpretive panels, ranger-led discussions, and a powerful film that meticulously details the events of November 29, 1864. This direct approach is essential, as the site’s power lies not in its physical grandeur, but in its historical gravity. Here, the abstract lines of a map collide with brutal reality. The historical range maps of the Cheyenne Nation illustrate a domain stretching across parts of what are now Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, and South Dakota. This was a land of plenty, where the Northern and Southern Cheyenne, along with their Arapaho allies, followed buffalo, managed resources, and maintained complex societal structures. The maps show a vibrant, self-sufficient nation. Sand Creek, however, marks the bloody intersection where the expanding lines of American settlement and the shrinking circles of indigenous sovereignty met with horrific violence.

The Cheyenne’s ancestral lands, as depicted on those historical maps, were gradually encroached upon through a series of treaties and aggressive expansionist policies. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, for instance, attempted to define tribal territories, including a vast area for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. Yet, the subsequent discovery of gold in Colorado in 1858 led to a massive influx of prospectors and settlers, effectively nullifying these agreements in practice. The Fort Wise Treaty of 1861, signed by only a minority of tribal leaders, drastically reduced the Cheyenne-Arapaho reservation to a fraction of their original lands, primarily a small tract along Sand Creek and the Arkansas River. It is this forced confinement, this drastic reduction of their mapped range, that sets the stage for the massacre. The site itself, a seemingly innocuous bend in a dry creek bed, was one of the last places where a peaceful band of Cheyenne and Arapaho, under Chief Black Kettle, believed they were safe, under the protection of the U.S. flag.

Walking the paths at Sand Creek, the interpretive signs guide you along the actual creek bed, past the locations where the village stood, where the attack commenced, and where the people desperately tried to flee. The map in your hand, provided by the National Park Service, overlays the historical events onto the present landscape. You see where the U.S. volunteer cavalry, led by Colonel John Chivington, launched their dawn attack on the sleeping village. You trace the flight paths of men, women, and children, many of whom were brutally murdered and mutilated despite displaying a white flag and the American flag. The 1851 Fort Laramie map might show an expansive, contiguous Cheyenne territory; the map of Sand Creek shows a fragment, a point of retreat, a final, tragic stand. The experience is visceral. The quiet air seems to carry echoes of cries, the rustle of tipis, the thundering hooves. This ground, marked by humble stone monuments and flags, tells a story of betrayal and genocide, a stark counter-narrative to the romanticized "manifest destiny" often found in conventional histories.

The true genius of the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is its unwavering commitment to presenting multiple perspectives and allowing the landscape to speak for itself. The visitor is encouraged to reflect, to feel, and to understand the profound impact of this event not just on the 200-plus victims, but on the trajectory of the entire Cheyenne Nation. It shattered trust, fueled decades of warfare, and solidified the American government’s policy of forced removal and reservation. The "historical range maps" that followed the massacre became ever smaller, ever more restrictive, charting a course of dispossession and cultural assault. Yet, amidst the sorrow, there is also a profound sense of Cheyenne resilience. The site also commemorates the living descendants, the vibrant cultures that persist, and the ongoing efforts to ensure this history is never forgotten. It’s a testament to the enduring spirit of a people who, despite unimaginable hardship, continue to honor their ancestors and reclaim their narrative.

For the traveler, this is not a site for casual sightseeing. It is a place for solemn reflection and deep learning. Plan to spend several hours, allowing ample time to walk the trails, read every interpretive panel, and absorb the atmosphere. The remote location means amenities are sparse. Bring water, snacks, and appropriate clothing for varying weather conditions. Comfortable walking shoes are a must. There are restrooms at the visitor contact station, but no food services. The nearest towns for lodging and supplies are Eads or Chivington, Colorado, both small and offering limited options. It is imperative to visit with respect: stay on marked paths, do not disturb any artifacts, and maintain a quiet demeanor. The National Park Service rangers are knowledgeable and sensitive; engage with them, ask questions, and listen to their insights.

Why does a trip to Sand Creek matter, especially in the context of historical range maps? Because maps, at their core, are human constructs, capable of both defining and erasing. They can represent claims of ownership, treaties of peace, or lines of conflict. By visiting a place like Sand Creek, you move beyond the abstract lines on a map and into the lived experience of those whose lands were charted, claimed, and tragically contested. You gain a visceral understanding of the devastating consequences of broken promises and unchecked power. It forces a critical examination of how history is written, whose stories are told, and how the physical landscape itself bears witness to past injustices.

In conclusion, the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is a powerful and essential destination for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of American history, indigenous sovereignty, and the true meaning behind the lines on a "Cheyenne Nation historical range map." It’s a place of profound sorrow, but also a testament to endurance and the enduring power of remembrance. It is a stark reminder that maps are never just about geography; they are about people, power, and the stories we choose to tell—or to ignore. Travel here not for entertainment, but for education, for reflection, and for a commitment to never forget the voices that echo across these quiet plains.