>

Navigating the Ancestral Depths: Experiencing Tsimshian Resource Lands from Prince Rupert

The mists often cling to the fjords around Prince Rupert, British Columbia, lending an ethereal quality to a landscape already steeped in profound history. This isn’t just a picturesque corner of the Pacific Northwest; it is the heart of the Tsimshian Nation’s traditional territory, a realm where every inlet, forest, and mountain holds generations of stories, livelihoods, and an intricate understanding of resource stewardship. For the intrepid traveler, approaching this region with an awareness of Tsimshian Nation maps of historical resource areas transforms a scenic journey into an immersive lesson in Indigenous land management, cultural resilience, and the enduring power of place.

To speak of "maps of historical resource areas" isn’t merely to conjure cartographic documents. It is to invoke a living, oral tradition, a sophisticated system of knowledge passed down through millennia. These are not static lines on paper, but dynamic narratives charting prime fishing grounds, vital hunting territories, ancient village sites, sacred ceremonial locations, and sustainable harvesting zones for cedar, berries, and medicinal plants. When you stand on the shores of Kaien Island, where Prince Rupert now stands, you are not just looking at a modern port city; you are gazing upon a nexus of these ancestral pathways and resource networks.

Our journey into understanding begins with the ocean, the lifeblood of the Tsimshian people. The coastal waters, teeming with life, represent the most extensive and vital "resource areas." From the churning waters of the Skeena River estuary, world-renowned for its salmon runs, to the protected inlets where oolichan once silvered the surface in their millions, these waters are meticulously mapped in Tsimshian oral histories. Imagine traveling through these waterways, not just as a passenger on a ferry or a kayak, but as someone tracing the routes of ancestral canoes, guided by knowledge of where the spring salmon would gather, where the eulachon (oolichan) nets were traditionally set, or where the best halibut banks lay.

The Tsimshian, meaning "People of the Skeena River," have always been master mariners and fishers. Their historical resource maps detail specific salmon streams – not just the Skeena itself, but countless tributaries and smaller rivers emptying into the ocean. Each stream has its distinct salmon run, its unique timing, and its specific Tsimshian caretakers. Today, while industrial fishing has impacted these resources, the knowledge of these areas persists. Visiting museums like the Museum of Northern BC in Prince Rupert offers glimpses into the tools and techniques – the intricate weirs, traps, and nets – used to harvest these resources sustainably, ensuring future abundance. Walking along the waterfront, one can almost hear the echoes of ancestral fishermen, their lives intrinsically linked to the ebb and flow of these rich waters.

Beyond salmon, the coastal environment provided an incredible array of marine resources. Shellfish beds, identified and managed for generations, offered vital protein. Seaweed harvesting locations, each with specific preparation techniques, provided essential nutrients. Even the powerful currents and tides, treacherous to the uninitiated, were mapped and understood as pathways and fishing advantages. A boat trip through the surrounding islands – perhaps towards the territories of the Gitxaala or Lax Kw’alaams Nations – allows one to visually connect with these maritime resource zones, seeing the kelp forests that shelter young fish, the rocky outcrops where mussels cling, and the deep channels where larger marine life thrives. The very act of navigating these waters becomes a tribute to the ancient knowledge that once guided every paddle stroke.

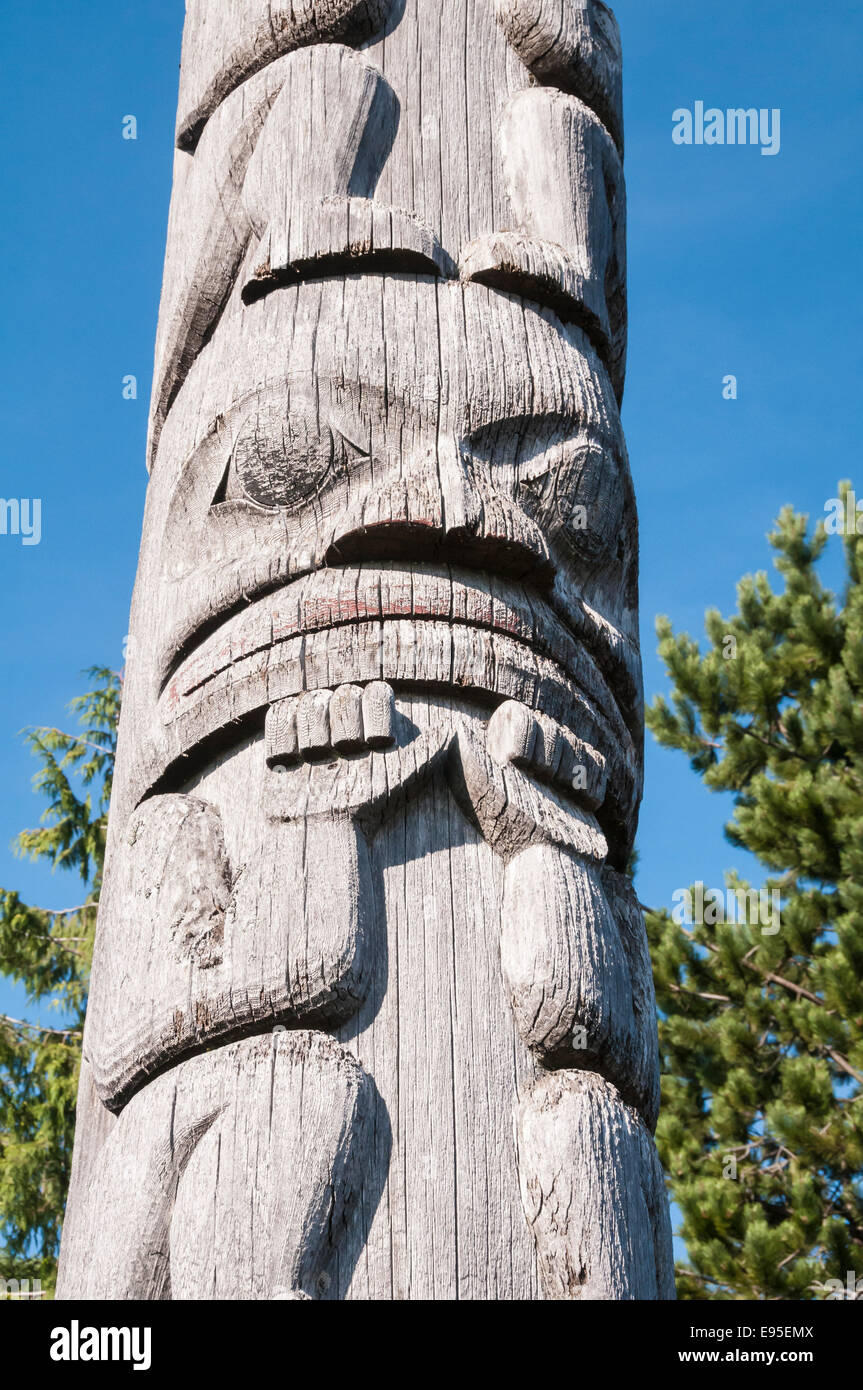

Moving inland from the water’s edge, the forest unfolds as another layer of Tsimshian historical resource maps. The mighty Western Red Cedar stands as a cultural keystone species, its presence defining vast "cedar resource areas." For the Tsimshian, cedar was not merely a tree; it was the "Tree of Life." Its bark was woven into clothing, baskets, and mats; its wood was carved into monumental longhouses, intricate canoes, towering totem poles, and essential tools. The oral maps would detail specific groves where bark could be harvested without harming the tree, or where ancient, straight-grained trees ideal for canoes could be found.

Exploring the lush temperate rainforests around Prince Rupert, perhaps on a guided hike in Butze Rapids Park or further afield, one can appreciate the significance of these cedar resource areas. Imagine a landscape where every large cedar tree could tell a story of its potential use – a canoe waiting to be born, a longhouse beam yet to be raised. Beyond cedar, the forests were also extensive "berry resource areas." Huckleberries, salmonberries, blueberries – each grew in specific microclimates, known and visited annually by Tsimshian families. These foraging grounds were not random; they were part of a managed landscape, where traditional burning practices or selective harvesting ensured continuous yields.

Interspersed within these natural resource zones are the "village sites" – historical resource areas in their own right, speaking volumes about the longevity of Tsimshian presence. Archaeological evidence across the territory reveals habitation sites dating back thousands of years, often strategically located at the confluence of resource-rich areas: near salmon streams, sheltered bays, and productive berry patches. These sites are not just remnants of the past; they are anchors of Tsimshian identity and claims to their traditional territories. While many are protected and not directly accessible to casual visitors, understanding their historical placement enriches any exploration of the Tsimshian landscape. The very land upon which Prince Rupert is built, for instance, overlays ancient Tsimshian settlements.

The concept of "trade routes" also forms a critical part of these historical resource maps. The Tsimshian were central to a vast Indigenous trade network, extending from the interior of British Columbia to the Alaskan coast. The Skeena River itself was a major highway, connecting coastal resources like oolichan grease and marine products with interior goods like furs and obsidian. These routes, meticulously known and traversed, were not just paths; they were cultural corridors, where knowledge, goods, and alliances were exchanged. Seeing the powerful flow of the Skeena, or navigating the intricate channels of the North Coast, one can visualize this ancient network, understanding how vital these arteries were to the economic and social fabric of the Tsimshian Nation.

For the contemporary traveler, engaging with the concept of Tsimshian historical resource maps offers a profound shift in perspective. It encourages a deeper, more respectful appreciation of the land and sea. It moves beyond superficial beauty to reveal layers of human interaction, sustainable practice, and cultural wisdom. It underscores that the land is not merely scenery but a complex, managed ecosystem that has sustained a vibrant culture for millennia.

How can a traveler experience this? While literal maps might not be readily available for public consumption (as they are often proprietary knowledge used for land claims and resource management by the Nation), the spirit of these maps is accessible through cultural engagement. Visiting the Kwinitsa Station Museum or the North Pacific Cannery National Historic Site near Port Edward provides historical context on the fishing industry and its impact, often featuring Indigenous perspectives. Seeking out local Indigenous tour operators (where available) offers invaluable direct insights, allowing Tsimshian guides to share their knowledge of specific areas and their cultural significance. Even simply reading about Tsimshian history and traditional ecological knowledge before visiting can transform the journey.

Ultimately, a trip to the Tsimshian traditional territory, with Prince Rupert as a natural base, is an invitation to see the world differently. It’s an opportunity to look at a mountain and understand it as a source of clean water and hunting grounds, to gaze at the ocean and recognize it as a pantry and a highway, and to walk through a forest and feel the presence of generations who lived harmoniously with its bounty. The Tsimshian Nation’s maps of historical resource areas, whether orally shared or visually represented, are not just about where things are; they are about how to live, how to thrive, and how to honor the profound, reciprocal relationship between people and their ancestral lands. To travel here with this understanding is to embark on a journey far richer than any conventional sightseeing tour – it is to touch the very essence of Indigenous stewardship and enduring cultural connection.