Tracing the Spirit of the Land: A Journey Through Little Bighorn’s Unseen Maps

The vast, undulating plains of southeastern Montana hold a story etched deep into the earth, a narrative often told through the lens of one culture, but profoundly shaped by another. We stand at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, a place synonymous with Custer’s Last Stand, but to truly understand this hallowed ground, we must shed the conventional cartographic gaze and instead seek the wisdom embedded in Native American maps – not always drawn on paper, but held in memory, oral tradition, and the very landscape itself. This is not merely a visit to a historical site; it is an invitation to perceive history through a different spiritual and geographical compass.

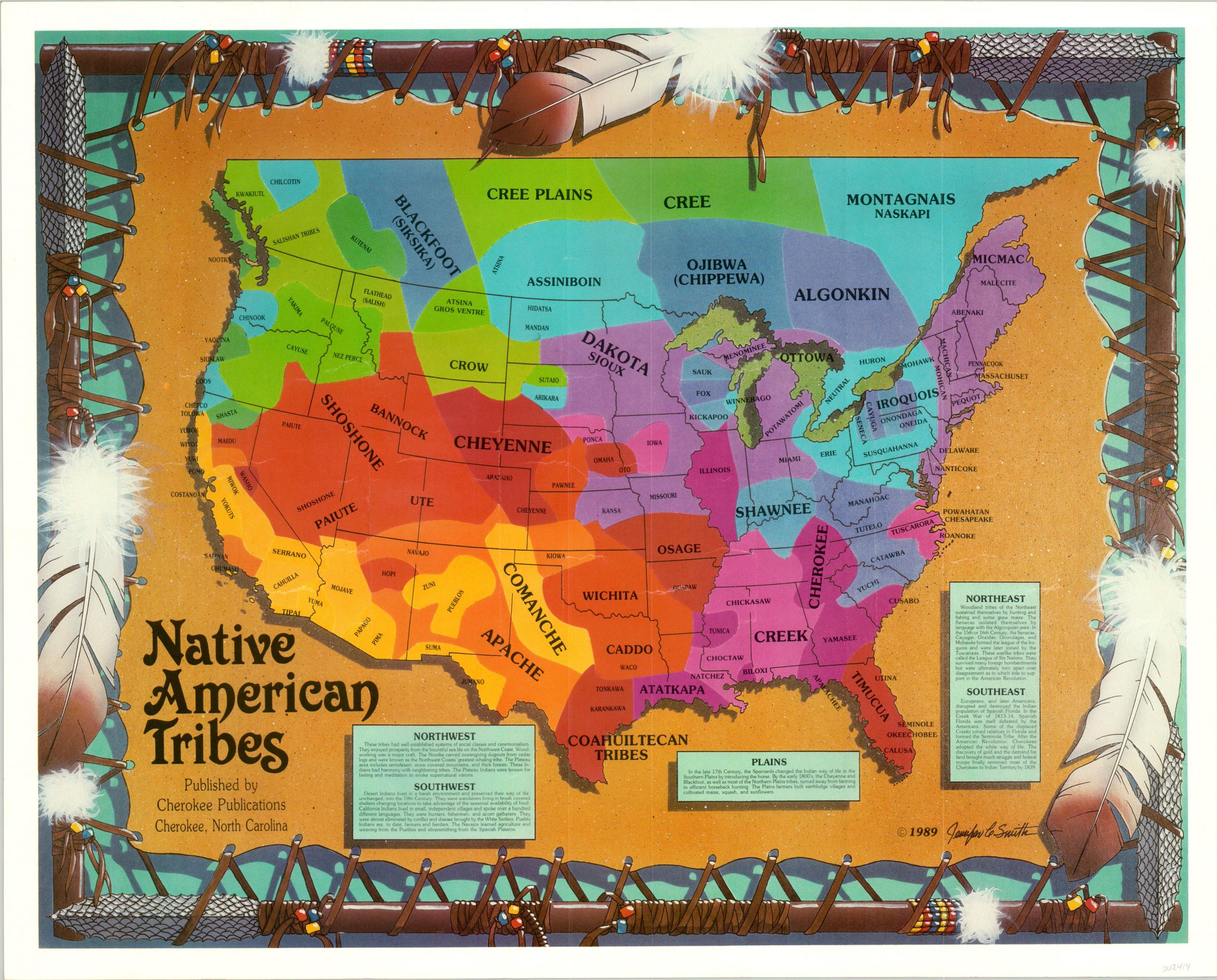

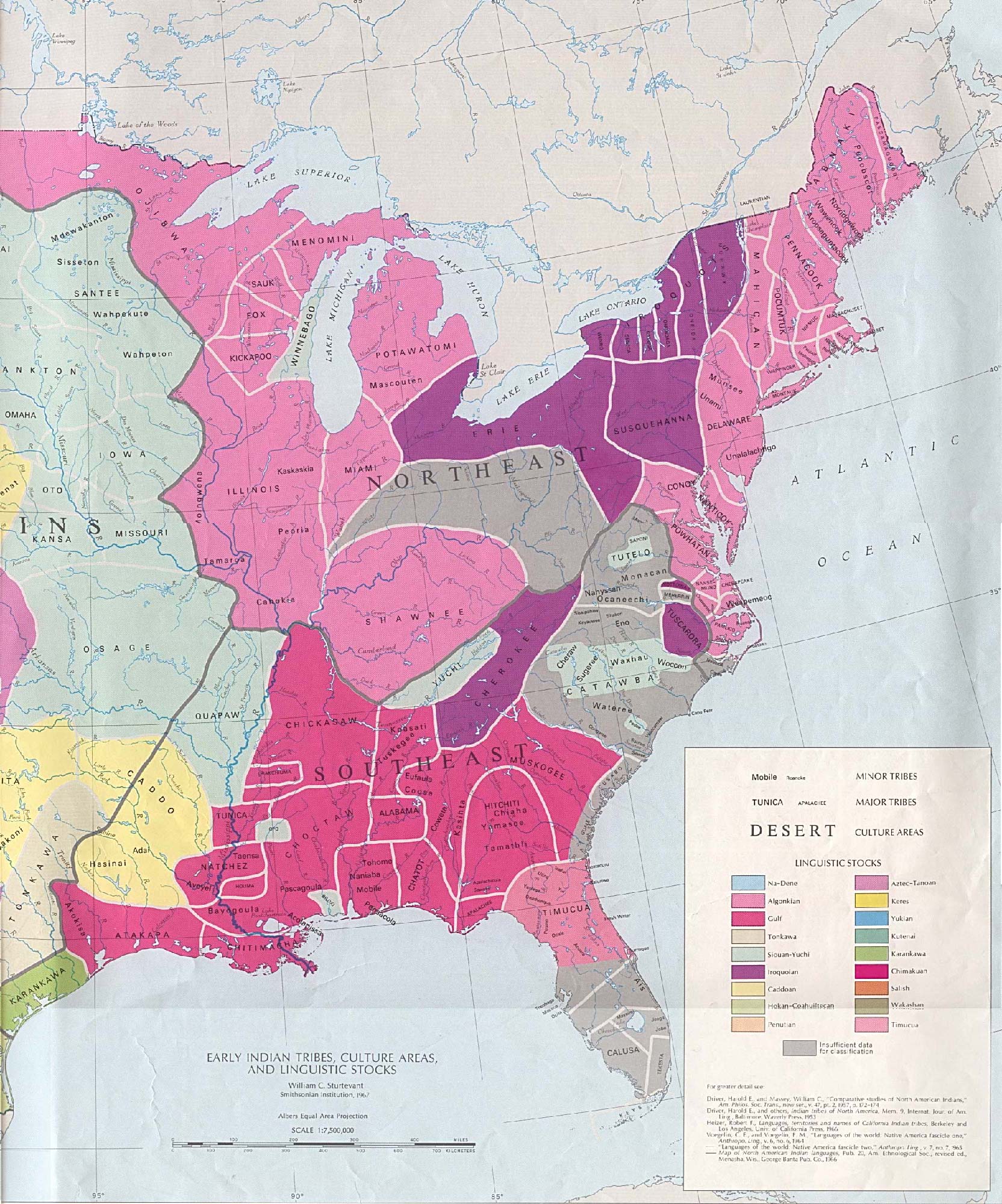

Imagine for a moment a map that breathes. Not a grid of precise coordinates and static lines, but a living tapestry of memory, movement, and meaning. For many Indigenous peoples of North America, maps were less about fixed boundaries and more about relationships: the flow of water, the migratory paths of buffalo, the location of sacred sites, the routes of ancestors, the places where spirits resided. They were mnemonic devices, often drawn in sand, on hides, or conveyed through song and story, depicting journeys, resources, warnings, and the spiritual essence of the land. When we approach historical battlefields like Little Bighorn through this Indigenous cartographic lens, the land ceases to be a passive backdrop and becomes an active participant, a repository of stories waiting to be re-read.

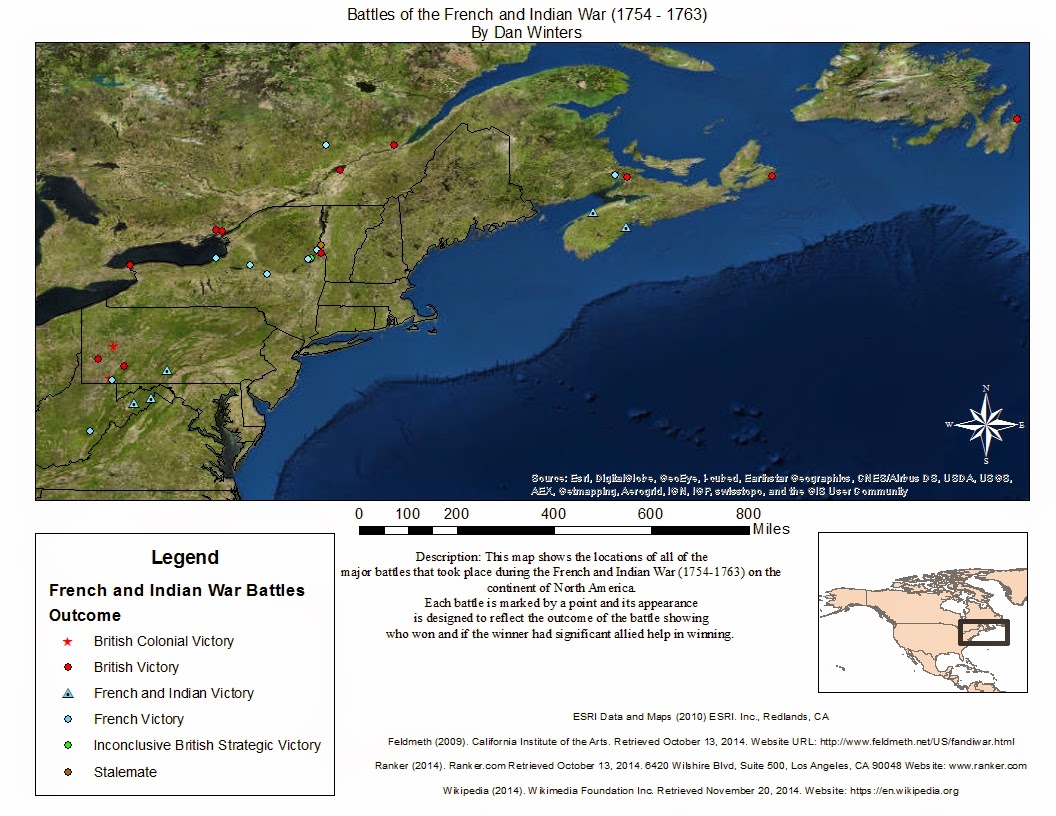

Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota as the Greasy Grass, is an ideal place to engage with this concept. Here, on June 25-26, 1876, the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho nations decisively defeated Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his 7th U.S. Cavalry. The standard narrative focuses on military strategy, tactical blunders, and the final, dramatic stand. But what if we tried to understand the battlefield as the Native American warriors did, informed by generations of intimate knowledge of this territory?

![]()

The Living Map of the Great Sioux Nation

Before Custer’s cavalry ever sighted the valley, the Lakota and Cheyenne had already charted this land through centuries of habitation. Their maps were not for conquest, but for survival and thriving. They depicted the prime buffalo hunting grounds, the reliable water sources of the Little Bighorn River, the protective coulees and ravines, and the sacred hills that offered vantage points and spiritual communion. The vast encampment of thousands of people and their horses along the river was not randomly placed; it was a testament to their understanding of the land’s capacity to sustain them, a living, breathing map of resource management and community.

When you stand on Last Stand Hill today, observing the distant ridges where Reno’s and Benteen’s commands were engaged, try to overlay an Indigenous map onto the scene. What you would "see" are not just lines of advance and retreat, but the wind’s direction carrying the sounds of battle, the sun’s position affecting visibility, the subtle contours of the terrain that offered cover or exposed a flank, the very grass underfoot that could hide a warrior or betray a movement. The Little Bighorn River itself, often seen by Western strategists as a mere obstacle or supply line, was to the Native people the lifeblood of their camp, a strategic barrier against attack from the east, and a critical escape route to the west. Its bends and banks were intimately known, each a potential ambush point or a place of concealment.

Reading the Landscape as a Narrative

Consider the flow of the battle itself. Custer’s plan involved a multi-pronged attack, dividing his forces. From a Western perspective, this is a calculated military maneuver. From an Indigenous perspective, it might be viewed as a profound misunderstanding of the landscape and the enemy. The Native warriors, intimately familiar with every fold and rise of the land, were able to use the terrain to their advantage. They didn’t need paper maps to know the fastest route through a coulee, where to hide horses, or how to outflank an enemy using natural cover. Their "maps" were internalized, a somatic knowledge passed down through generations of hunting, raiding, and living on these plains.

Walk the path to Medicine Tail Coulee, the gully where Custer’s command likely attempted to ford the river before being repulsed. Imagine the warriors, not just as fighters, but as cartographers in motion. Their decisions – where to position themselves, when to charge, where to retreat – were instantaneous interpretations of this living map. The terrain became their ally, guiding their movements, dictating their tactics. The ravines that Custer’s men struggled to navigate became pathways for the Lakota and Cheyenne. The open ridges that exposed the cavalry became advantageous firing positions for the defenders.

The Echoes of Oral Tradition

Many Native American maps were not visual but oral. The stories told around campfires, passed from elder to child, contained geographical information. "Go past the lone cottonwood tree, over the ridge where the buffalo often graze, and down to the fork in the river where the eagles nest." These narratives were rich with place names, not just as labels, but as descriptors of events, resources, and spiritual significance.

At Little Bighorn, the markers for fallen soldiers are stark white, while those for Native warriors are red, subtly acknowledging the two distinct perspectives. But to truly engage with the Indigenous "map," one must go beyond these markers. Visit the interpretive exhibits at the visitor center, specifically seeking out the Native American perspectives. Listen to ranger talks that incorporate Indigenous oral histories. But most importantly, spend time in silence, allowing the wind to carry the whispers of the past. Try to imagine the land as it was before the fences and monuments, a vibrant, living space teeming with buffalo, camps, and the sounds of a thriving culture.

The Unseen Routes of Memory and Resilience

The Native American maps of battlefields extend beyond the conflict itself. They include the routes of forced removal, the sacred sites that were desecrated, and the enduring resilience of a people. At Little Bighorn, the maps also speak of the aftermath: the gathering of the dead, the stories told and retold to ensure the memory of the victory, and the subsequent efforts to protect their lands and way of life. These are maps of survival, of resistance, and of the profound connection to the land that persists despite centuries of struggle.

Visiting Little Bighorn with this expanded understanding of "maps" transforms the experience. It is no longer just a static tableau of a historical event, but a dynamic, multi-layered landscape. You begin to see the river not just as a river, but as a boundary, a sanctuary, a witness. The hills are not just hills, but vantage points, spiritual anchors, places of strategic importance. The vastness of the plains is not emptiness, but a canvas for movement, a provider of sustenance, and a silent observer of human drama.

Practicalities for the Conscious Traveler

To truly engage with Little Bighorn through this Indigenous lens, consider the following:

- Allocate Time: Don’t rush. Spend a full day, or even two, exploring the monument. Walk the trails, drive the auto tour, and spend time in quiet reflection.

- Engage with All Interpretations: While the primary narrative at the monument has historically been U.S. Cavalry-centric, the interpretive center and ranger talks increasingly incorporate Native perspectives. Seek these out.

- Read Before You Go: Research books and articles written by Indigenous historians or those that prioritize Native accounts of the battle and the history of the Northern Plains tribes. This pre-work will enrich your visit immensely.

- Visit the Indian Memorial: This powerful memorial offers a crucial counter-narrative and a space for reflection on the sacrifices and resilience of the Native nations.

- Respect the Land: Remember that this is sacred ground for many. Be mindful of your actions, stay on marked paths, and leave no trace.

- Seek Local Indigenous Voices (if possible): While formal tours by Native guides might be limited directly at the monument, look for opportunities in nearby communities to learn from local Indigenous people about their history and connection to the land.

- Embrace the Elements: The weather on the plains can be extreme. Dress in layers, bring water, and be prepared for sun, wind, or sudden changes. These elements are part of the "map" experience.

Conclusion: A Deeper Cartography

To visit Little Bighorn with an appreciation for Native American maps is to embark on a journey of deeper understanding. It is to move beyond the rigid lines of conventional history and embrace a more fluid, spiritual, and embodied cartography. It challenges us to see the land not just as geography, but as biography – a living testament to the struggles, triumphs, and enduring spirit of its Indigenous peoples.

By consciously seeking out these unseen maps, we gain not only a richer historical perspective but also a profound respect for the intimate knowledge and spiritual connection Indigenous cultures hold with the land. It’s a call to rethink our understanding of place, memory, and history, inviting us to become more discerning travelers, capable of reading the subtle, powerful stories etched into the very soul of the earth. This journey to Little Bighorn, seen through the lens of Indigenous maps, is a pilgrimage to the heart of American history, redefined.