Tracing Dispossession: A Journey Through Maps at The Ancestral Lands & Colonial Traces Museum

Stepping into The Ancestral Lands & Colonial Traces Museum isn’t just a visit; it’s an immediate, visceral encounter with history’s fault lines, where lines on paper became instruments of profound transformation. Located in the heart of what was once hotly contested territory – a region rich with Indigenous heritage and layered with colonial ambition – this institution offers a singular, essential perspective for the discerning traveler: a deep dive into Native American maps of colonial land grants. Forget the typical museum gift shop preamble; here, the story begins the moment you cross the threshold, pulling you into a narrative told not just through artifacts, but through the very language of the land itself.

The museum occupies a strikingly modern, yet thoughtfully integrated building, its architecture echoing both the natural contours of the landscape and the sharp, deliberate angles of colonial demarcation. The use of local stone and timber creates an immediate connection to the earth, subtly preparing you for the profound discussions held within its walls. Upon entry, the ambiance is one of quiet reverence, but also a palpable intellectual energy. There’s no bustling café at the immediate entrance, no distraction; instead, a vast, illuminated floor map of the region, showing pre-contact Indigenous territories, immediately sets the stage. It’s a powerful, silent overture to the complex symphony of history you’re about to experience.

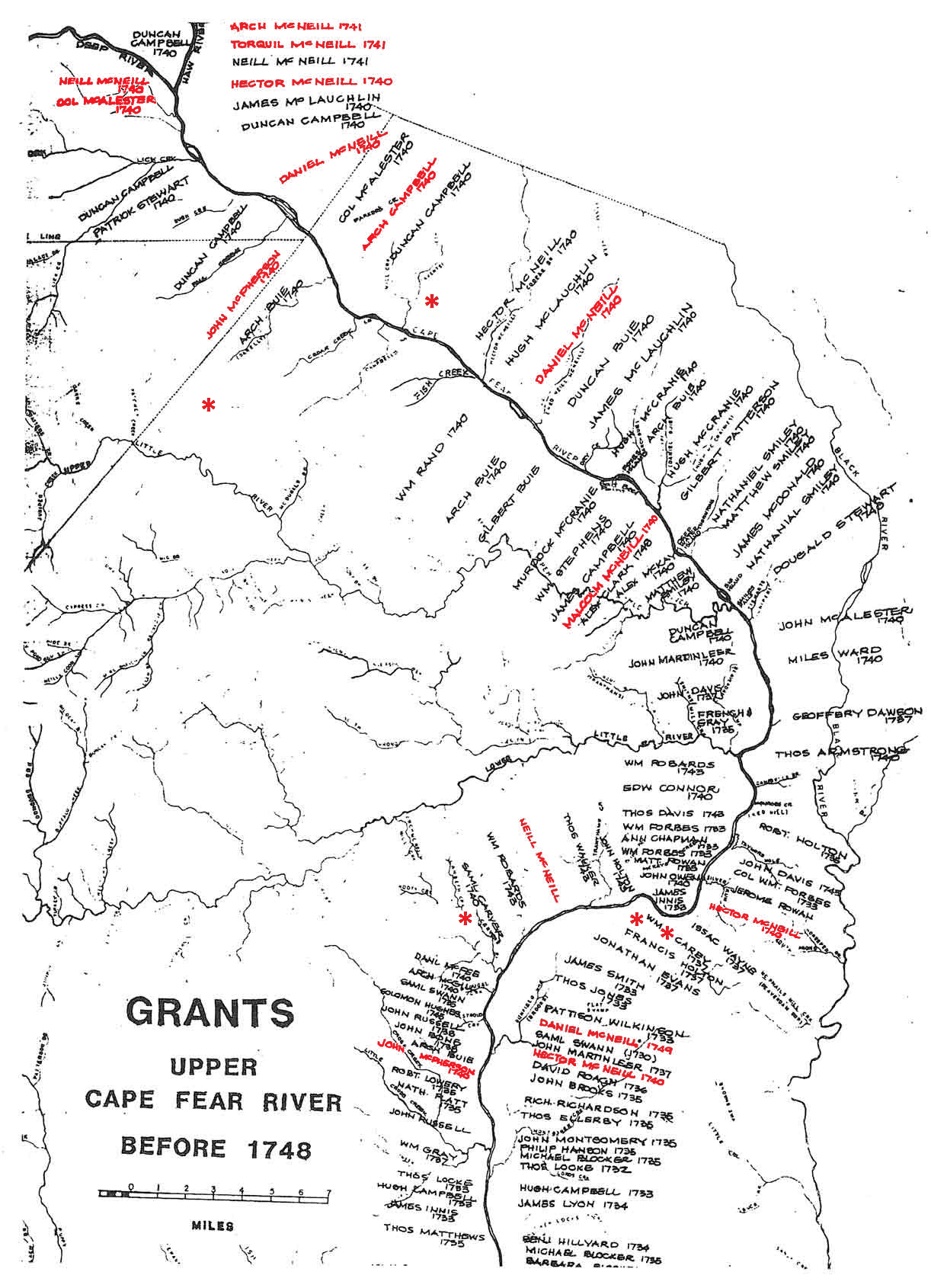

The core of the museum’s exhibition lies in its remarkable collection and interpretation of cartographic materials. This isn’t just about old documents; it’s about understanding how two vastly different worldviews intersected, clashed, and ultimately shaped the continent we know today. The exhibits meticulously juxtapose European survey maps – with their precise grids, metes and bounds, and declarations of ownership – alongside the Indigenous understanding of land, often conveyed through oral traditions, mnemonic devices, wampum belts, or drawings that depicted relationships, resources, and routes rather than arbitrary lines of property.

One of the most impactful galleries is "The Cartographic Clash." Here, you find meticulously recreated colonial land grant documents, often featuring elegant script and elaborate seals, detailing parcels "purchased" or "claimed" from Indigenous peoples. These are displayed alongside visual interpretations of how the Native inhabitants would have understood their territories: not as static, bounded rectangles, but as living landscapes of shared resources, seasonal migration paths, sacred sites, and intricate social networks. The contrast is stark and immediate. European maps sought to contain and possess; Indigenous maps (or mapping traditions) sought to relate and sustain.

For example, a section might feature a 17th-century royal grant from a European monarch, detailing thousands of acres ‘given’ to a colonial proprietor. Adjacent to it, an interpretive panel illustrates how the local Indigenous nation would have conceptualized that same area – perhaps a network of fishing weirs along a river, hunting grounds in the forest, and ancestral burial sites. The museum brilliantly uses interactive digital displays to overlay these different perspectives onto contemporary satellite imagery, allowing visitors to see the historical layers on the very ground they now stand upon. You can trace a colonial "purchase" line and then, with a swipe, reveal the Indigenous pathways and resource zones that crisscrossed it, often rendering the colonial line utterly meaningless in the Indigenous worldview.

The genius of this museum lies in its ability to humanize these abstract lines on paper. The exhibits don’t just show maps; they tell the stories behind them. There are moving accounts of negotiations, often fraught with misunderstanding and power imbalances. You learn about "walking purchases," where the amount of land granted was determined by how far a man could walk in a day, often with a team of swift runners hired by colonists, vastly expanding the claimed territory beyond what Indigenous leaders might have anticipated or agreed to. The maps become evidence of these historical injustices, not just inert historical curiosities.

Beyond the stark visual comparisons, the museum delves into the very philosophy of ownership. European maps were instruments of law and commerce, defining what could be bought, sold, and inherited. They were tools of a sedentary, agricultural society. Indigenous mapping, on the other hand, often reflected a deeper, spiritual connection to the land – a reciprocal relationship of stewardship, not ownership. Land was understood as something to be cared for, shared, and respected, not a commodity to be exploited. This fundamental philosophical difference is expertly explored through multimedia presentations, oral histories from contemporary Indigenous elders, and reproductions of early colonial accounts that highlight the profound communication breakdown.

One particularly compelling exhibit focuses on "The Invisible Lines." Here, the museum explores how European cartography often depicted vast swathes of Indigenous territory as terra nullius – "empty land" – despite millennia of habitation and intricate land use. The exhibits show early European maps with large, blank spaces or decorative embellishments where Indigenous nations thrived, effectively erasing their presence cartographically before their physical displacement. This section powerfully illustrates how maps were not just neutral representations of reality but active participants in shaping colonial ideology and justifying expansion.

The "Voices of Resistance" gallery offers a vital counter-narrative. It showcases instances where Indigenous leaders and nations actively resisted colonial encroachment, often using their own understanding of the land and their own diplomatic traditions to push back against colonial claims. While formal Indigenous maps in the European sense were rare, the museum presents fascinating examples of Indigenous counter-claims articulated through speeches, wampum belts used as diplomatic records, and even early drawings that visually disputed colonial boundaries. These exhibits underscore the resilience and agency of Indigenous peoples in the face of overwhelming pressure.

Accessibility at The Ancestral Lands & Colonial Traces Museum is excellent, with ramps, elevators, and clear pathways throughout. Informative panels are presented in multiple languages (English and relevant Indigenous languages where appropriate, along with Spanish), and audio guides offer deeper insights and personal narratives. While there isn’t a full-service restaurant, a small, thoughtfully curated café offers light refreshments and local Indigenous-inspired snacks, providing a moment for reflection amidst the weighty historical discussions. The gift shop, far from being a collection of tourist trinkets, features authentic Indigenous artwork, books by Native authors, and educational materials, encouraging visitors to continue their learning journey.

Leaving The Ancestral Lands & Colonial Traces Museum, one carries a profound sense of shifted perspective. The familiar landscape outside – the roads, the towns, the fields – now feels imbued with layers of unseen history. You begin to understand that every plot of land, every property deed, has a story that extends far beyond its legalistic origins. The lines on contemporary maps, which we often take for granted, are revealed as the end product of centuries of negotiation, conflict, and often, dispossession.

For the conscious traveler, for anyone interested in the true history of the Americas, and for those who seek to understand the ongoing complexities of Indigenous land rights, this museum is an indispensable destination. It’s more than just a place to see old maps; it’s an invitation to engage with the profound power of cartography, to recognize the competing visions of land, and to grapple with the enduring legacy of colonial land grants. It challenges us to look beyond the surface of the land we inhabit and to acknowledge the ancestral traces beneath, forever etched, not just in the earth, but in the compelling stories that maps – both Indigenous and colonial – continue to tell. This isn’t just history; it’s the foundational story of a continent, and it’s presented here with an urgency and clarity that resonates long after your visit concludes.