Tracing Ancient Pathways: Navigating the Chesapeake’s Early Contact Zones

Forget the glossy brochures and predictable itineraries. True travel, for me, is about peeling back layers of time, understanding the ground beneath your feet not just as soil and rock, but as a living tapestry of human experience. My latest journey took me deep into the heart of what many maps label simply as "Virginia," but which, to those who truly listen, speaks volumes of Tsenacommacah – the ancestral lands of the Powhatan people, and a profound early contact zone between Indigenous nations and European newcomers. This is not just a destination; it’s an immersive historical cartography, where the landscape itself becomes the map.

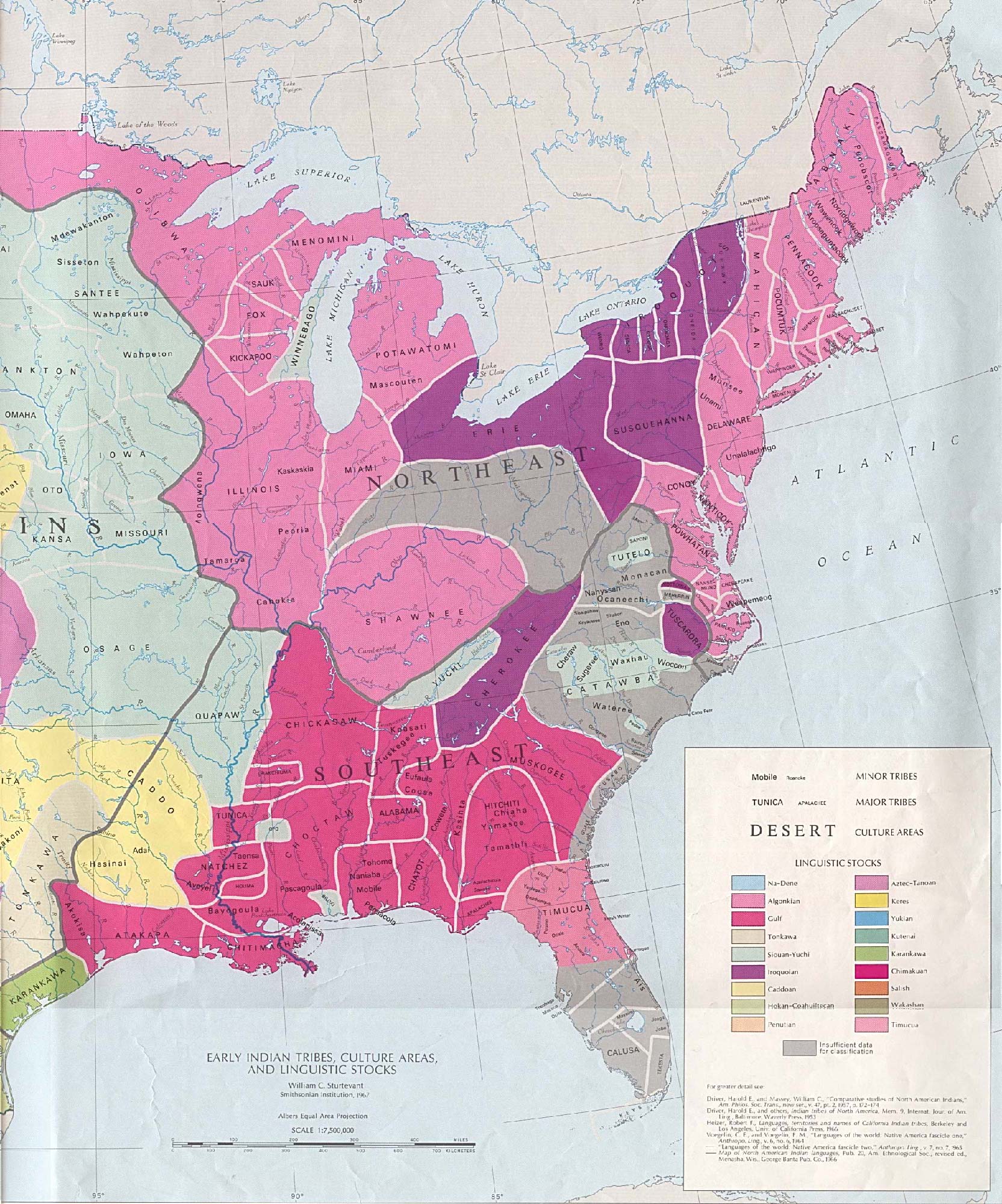

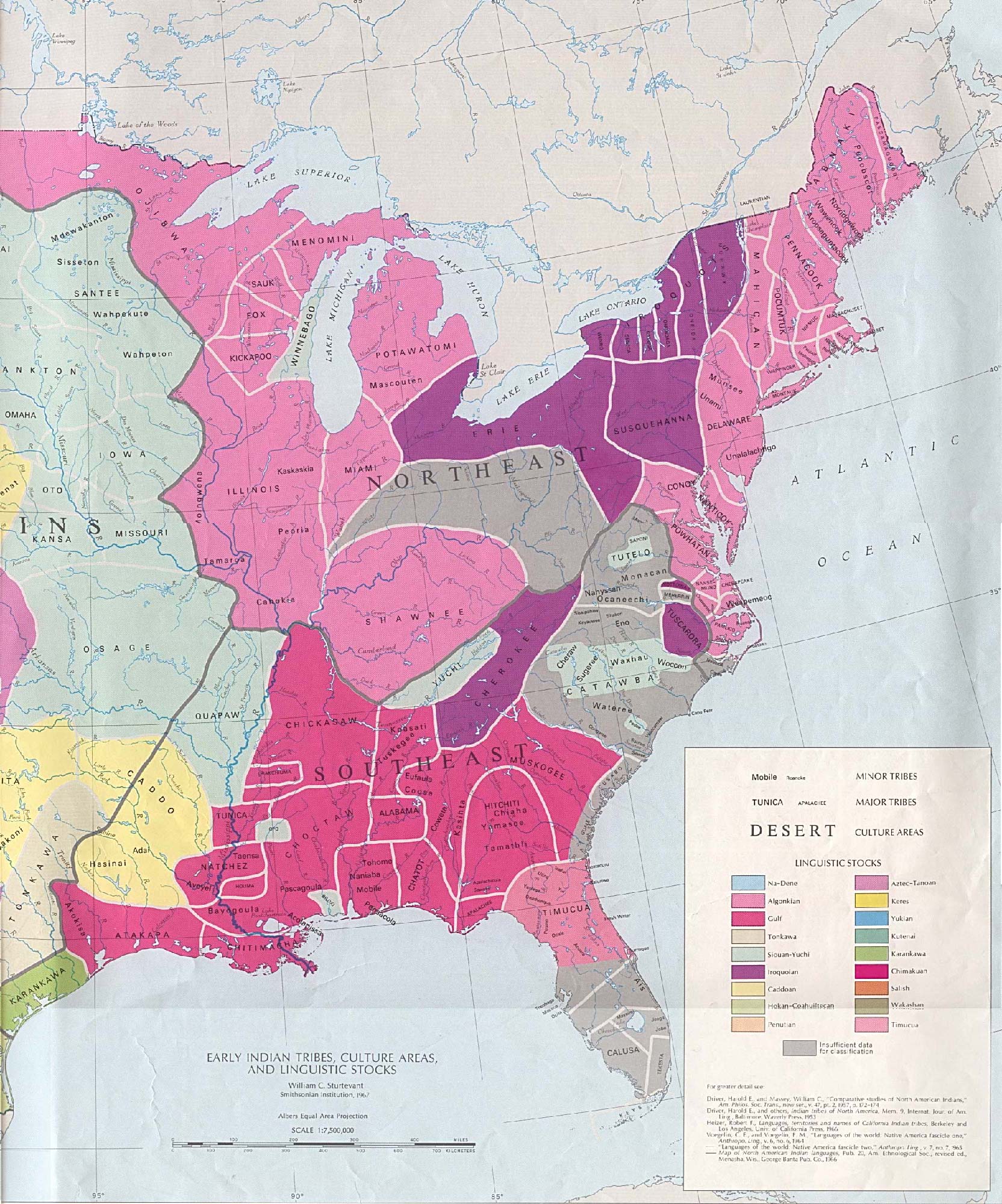

The Chesapeake Bay, a vast estuary where rivers like the James, York, and Potomac spill into the Atlantic, is a place of breathtaking beauty and profound historical weight. Today, it’s a haven for sailors, kayakers, and nature lovers. But for centuries before European arrival, it was a meticulously managed, resource-rich homeland for numerous Algonquian-speaking tribes, unified under the formidable leadership of Chief Powhatan. To understand this place, you must shed the European-centric notion of maps as static, two-dimensional grids. Native American "maps" were dynamic, mnemonic, deeply intertwined with oral histories, ecological knowledge, sacred sites, and the very act of living on the land. They were stories told through trails, river currents, seasonal migrations of game, and the locations of ancestral villages.

My exploration began where the James River widens, near the historic triangular fort of Jamestown. Standing on the archaeologically rich grounds of Historic Jamestowne, you’re presented with a stark contrast in spatial understanding. The English settlers arrived with compasses, quadrants, and a mindset of ownership and division, ready to carve up the "New World" into parcels. They sought gold, a passage to the Pacific, and a defensible position. Their maps were about navigation, territorial claims, and strategic advantage.

But step away from the reconstructed fort and walk along the riverbanks, letting the wind carry the scent of marsh grass. Imagine this land through Powhatan eyes. The river wasn’t just a route to the sea; it was a lifeblood, a provider of fish, oysters, and travel. The surrounding forests were not wilderness to be tamed, but meticulously understood ecosystems – sources of timber, game, medicinal plants, and sacred spaces. The trails crisscrossing the peninsula weren’t arbitrary lines but ancient pathways connecting villages, hunting grounds, and ceremonial sites, each turn and landmark imbued with meaning and memory. These were the true maps of the land, passed down through generations.

To truly appreciate this, a visit to the Jamestown Settlement is essential. While it primarily depicts the English experience, its meticulously recreated Powhatan village offers a crucial counterpoint. Walking among the yehakin (reed houses), observing the craftspeople demonstrating traditional skills like pottery, weaving, and canoe building, you begin to grasp the sophistication of Powhatan society. The village layout itself is a map – reflecting community structure, resource management, and a deep connection to the environment. The interpreters, many of whom are descendants of Virginia’s Indigenous peoples, speak not just of history but of an enduring culture, helping bridge the gap between textbook facts and living heritage. They articulate how knowledge of the land, its rhythms, and its bounty was the ultimate map for survival and prosperity.

But the story isn’t confined to Jamestown. The early contact zones stretched far beyond, encompassing the entire Powhatan Confederacy. Perhaps one of the most poignant and powerful "non-sites" to visit (as public access is restricted to preserve its integrity) is Werowocomoco, Chief Powhatan’s capital. Located on the York River, a short drive from modern-day Williamsburg, Werowocomoco was not just a political center but a spiritual and economic hub. For centuries, it served as a meeting place, a center for trade and tribute, and the seat of power for one of the most influential Native American leaders in North American history.

While you cannot simply walk into Werowocomoco, its significance looms large over the entire region. Its spirit can be felt by kayaking or canoeing the York River, imagining the hundreds of dugout canoes that would have plied these waters, carrying goods, emissaries, and warriors. From the river, you can gain a sense of the strategic genius of its location – defensible, accessible, and central to the Confederacy’s vast network. The very act of seeking out Werowocomoco, even if only to view its general location from a distance, forces you to re-center your understanding of the landscape. It demands that you acknowledge the power and presence that predated European settlement, shifting the narrative from a "discovery" to an encounter on Indigenous terms.

Consider the famous map drawn by Captain John Smith in 1612. Often lauded as a masterpiece of early colonial cartography, it was, in fact, heavily reliant on Native American guides and knowledge. Smith didn’t just wander aimlessly; he was led, informed, and sometimes misled by the very people whose lands he was charting. Their mental maps, their oral directions, their understanding of the rivers and tributaries, the locations of villages and hostile territories – all contributed to Smith’s published work. The irony is that this European map, intended to aid colonial expansion, inadvertently preserves fragments of the Indigenous spatial understanding of Tsenacommacah. When you look at Smith’s map today, overlaid with modern satellite imagery, you can see the remarkable accuracy of the river systems, an accuracy only achievable with local, Native guidance.

To fully immerse yourself in these early contact zones, one must also embrace the natural environment. Spend time walking the Colonial Parkway, a scenic drive that connects Jamestown, Williamsburg, and Yorktown. But instead of just admiring the manicured landscapes, consider the deeper history. Pull over at the numerous overlooks and gaze at the rivers and forests. This is where the landscape itself becomes a living document. The marshlands, the cypress swamps, the rich agricultural lands – these were the resources that sustained the Powhatan people for thousands of years. Their "maps" detailed the best fishing spots, the prime hunting grounds for deer and turkey, the locations of wild rice and berry patches. They understood the seasonal cycles, the migratory patterns, and the subtle signs of the land in a way Europeans could only dream of.

For a more active exploration, rent a kayak or paddleboard on the James or York River. From the water, the world shifts. The banks rise up differently. You begin to appreciate the scale of the waterways that served as ancient highways. You might even spot an eagle, a species revered by many Native American cultures, soaring overhead – a timeless presence connecting past and present. This perspective from the water, the original highways, offers a direct sensory connection to the Indigenous way of traversing and understanding this land.

Beyond the specific historical sites, the enduring presence of Virginia’s Indigenous nations is vital. Seek out opportunities to learn from contemporary tribes like the Mattaponi, Pamunkey, Chickahominy, and others who continue to thrive in their ancestral homelands. Many maintain cultural centers and host public events where you can experience their rich traditions, listen to their stories, and understand how their connection to the land and its history remains unbroken. These interactions are perhaps the most authentic way to engage with the living legacy of "Native American maps" – not as ancient relics, but as living knowledge systems that continue to inform and shape their communities.

In conclusion, a journey to the Chesapeake’s early contact zones is far more than a historical tour; it’s an exercise in re-mapping your own understanding of the world. It’s about recognizing that "maps" come in many forms – etched in rock, woven into stories, encoded in the very ecosystem. It’s about seeing the landscape not just as a backdrop to European arrival, but as a vibrant, complex homeland with its own rich history and enduring Indigenous presence. This profound experience challenges you to look beyond the lines on modern charts and instead, feel the pulse of ancient pathways, understanding that every river, every forest, every stretch of marshland holds a story, a memory, and a map of a world that was, and in many ways, still is. It’s a journey that leaves you not just with photos, but with a profoundly altered perspective on history, geography, and the power of place.