The Living Map: Tracing History and Identity on the Tohono O’odham Nation Reservation

The map of the Tohono O’odham Nation is far more than a mere geographical outline; it is a profound narrative etched in the Sonoran Desert, a testament to endurance, identity, and an unbroken connection to ancestral lands. For the traveler or history enthusiast, understanding this map means delving into millennia of human adaptation, centuries of colonial impact, and the ongoing saga of a sovereign people asserting their right to self-determination. This article unravels the layers of history and identity woven into the very fabric of the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation map, inviting a deeper appreciation for this unique corner of North America.

The Land Before the Lines: Deep Roots in the Sonoran Desert

To truly comprehend the Tohono O’odham Nation map, one must first erase all modern boundaries and envision the vast, fluid territory that existed for thousands of years. The ancestors of the Tohono O’odham, known as the "Desert People," have inhabited the Sonoran Desert for at least 4,000 years, cultivating a deep, intimate relationship with its challenging yet bountiful environment. Their traditional lands, known as Hia C-eḍ O’odham, stretched across what is now southern Arizona and northern Sonora, Mexico.

This wasn’t a static, defined territory in the European sense, but a dynamic homeland shaped by seasonal movements, resource availability, and a complex network of trade and cultural exchange. The O’odham developed sophisticated irrigation techniques, cultivated drought-resistant crops like corn, beans, and squash, and harvested native plants like the saguaro fruit, cholla buds, and mesquite beans. Their knowledge of the desert was encyclopedic, their spiritual beliefs deeply intertwined with its mountains, washes, and unique flora and fauna. Mountains like Baboquivari Peak, the sacred home of the Creator I’itoi, served as spiritual anchors, guiding the people and grounding their identity.

This pre-colonial map was a mental construct, passed down through generations of oral tradition, marked by natural landmarks and sustained by a way of life – O’odham Himdag – that emphasized balance, reciprocity, and respect for the land. It was a map of sustenance, ceremony, and community, long before any lines were drawn on paper.

The Imposition of Lines: A Crucible of Colonialism

The tranquility of this ancestral map was shattered by the arrival of European powers, beginning with Spanish explorers and missionaries in the late 17th century. The Spanish introduced new diseases, livestock, and a foreign concept of land ownership. While the O’odham resisted outright conquest, their lives were irrevocably altered by missionization, resource exploitation, and the imposition of a colonial hierarchy.

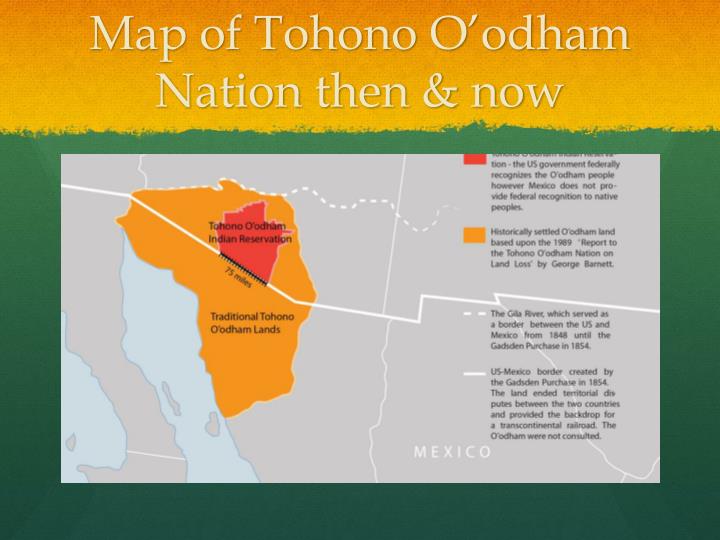

The most dramatic and enduring incision on the O’odham homeland, however, came much later, with the signing of the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. This agreement between the United States and Mexico arbitrarily drew a new international border across the heart of O’odham territory, effectively bisecting families, communities, and ancient trade routes. Overnight, people who had shared a common language, culture, and lineage found themselves separated by a political line, becoming "Americans" on one side and "Mexicans" on the other. This act of drawing a line through a living culture remains a raw wound and a defining feature of the Tohono O’odham experience to this day.

Following the Gadsden Purchase, the fragmented O’odham people faced increasing pressure from American settlers, miners, and ranchers. The US government, driven by policies of assimilation and land acquisition, began to confine Native American tribes to reservations. For the O’odham, this process was protracted and piecemeal, resulting in the establishment of several distinct land bases. The San Xavier Reservation (1874), the Gila Bend Reservation (1882), and eventually, the vast main Tohono O’odham Reservation (established in stages, primarily 1916-1934) became the new, defined boundaries of their homeland.

The Reservation Map Takes Shape: A New Reality

The modern map of the Tohono O’odham Nation is a complex patchwork, a direct consequence of these historical forces. The main reservation, encompassing nearly 2.8 million acres, is the second-largest Indian reservation by area in the United States, comparable in size to the state of Connecticut. It is, however, not a single contiguous block. The map reveals three distinct geographical units:

- The Main Reservation: This vast expanse, home to the capital Sells, stretches across southern Arizona, bordering Mexico for 75 miles.

- San Xavier Reservation: Located just south of Tucson, it’s a smaller, economically vibrant community.

- Gila Bend Reservation: Situated north of the main reservation, near the town of Gila Bend.

These separate land bases reflect the historical circumstances of their establishment and the diverse experiences of different O’odham bands. Yet, despite the fragmentation on paper, the Tohono O’odham Nation operates as a unified, federally recognized sovereign government. The map of the reservation is further divided into 11 administrative districts, each with its own district council, reflecting a deeply ingrained tradition of local governance within a larger tribal structure.

The geographical features within these mapped boundaries are also significant. The majestic Baboquivari Peak, mentioned earlier, stands prominently on the main reservation, its spiritual importance undiminished by modern lines. The map also delineates ephemeral rivers, vast desert plains, and numerous mountain ranges – all integral to the O’odham Himdag.

Reading the Map: Geography, Culture, and Modern Challenges

For a visitor, understanding the Tohono O’odham Nation map means recognizing it as a living document that intertwines physical geography with cultural identity and contemporary realities.

Physical Geography: The map showcases the raw beauty and harshness of the Sonoran Desert. Expect to see saguaro cacti forests, creosote bushes, and palo verde trees dominating the landscape. The climate is extreme, with scorching summers and mild winters, dictating much of the traditional O’odham way of life and modern land use. Washes and arroyos, though often dry, become powerful waterways during monsoon season, shaping the terrain and providing essential moisture.

Cultural Geography: Beyond the physical, the map implicitly marks a cultural landscape. Traditional harvesting grounds, ancient trails, and ceremonial sites are all located within these boundaries, even if not explicitly labeled for public viewing. The location of communities like Sells, Topawa, and Santa Rosa reflects historical settlements and resource access. The very roads crisscrossing the reservation often follow ancient pathways, connecting current communities to their past.

Political Geography: The map is a powerful symbol of tribal sovereignty. The Tohono O’odham Nation is a self-governing entity with its own constitution, judicial system, and police force. Understanding this means recognizing that you are entering a distinct nation, where tribal laws and customs apply. The map, therefore, defines a political space where the Tohono O’odham people exercise their inherent rights.

The US-Mexico Border: Perhaps no other feature on the map carries as much weight and controversy as the 75-mile stretch of the US-Mexico border that dissects the main reservation. This line, a legacy of the Gadsden Purchase, remains a profound challenge to O’odham identity and way of life. It divides families, disrupts traditional ceremonies, and impacts the free movement of people and wildlife. The map here signifies not just a political boundary, but a daily struggle for cultural integrity and human rights, as increased border enforcement impacts a sovereign nation and its citizens.

Identity and Resilience: Beyond the Boundaries

The Tohono O’odham Nation reservation map, with all its historical scars and political realities, ultimately tells a story of unparalleled resilience. Despite centuries of external pressures, the O’odham have maintained their distinct identity, their language (Tohono O’odham is still widely spoken), and their deep spiritual connection to the land.

The map represents the land base from which they continue to practice O’odham Himdag. Traditional ceremonies, such as the Nawait (rain ceremony) and the Saguaro Harvest, are vital expressions of this living culture. The saguaro cactus, an iconic desert plant, is not just a symbol of the Southwest but a sacred resource for the O’odham, its fruit providing sustenance and its very presence defining their homeland.

Today, the Tohono O’odham Nation leverages its sovereignty within these mapped boundaries to address modern challenges. This includes managing scarce water resources, pursuing economic development (including casinos, agriculture, and tourism), providing education and healthcare to its members, and advocating for its rights on the national and international stage, particularly concerning the border. The map is their foundation, their claim to a future that is both modern and deeply rooted in tradition.

For the Visitor and Learner: Engaging with the Living Map

For those interested in exploring the Tohono O’odham Nation, whether virtually or in person, a respectful and informed approach is paramount.

- Acknowledge Sovereignty: Remember you are on sovereign land. Respect tribal laws, customs, and privacy.

- Seek Education: Visit cultural centers (like the Tohono O’odham Cultural Center & Museum in Topawa, though access can be limited), engage with educational materials, and learn about their history and contemporary issues.

- Support Local: If permitted, support tribal enterprises, artists, and businesses.

- Respect the Land: The desert is a fragile ecosystem and a sacred space. Practice Leave No Trace principles.

- Understand the Border: Be aware of the complex and sensitive nature of the border region within the reservation.

The map of the Tohono O’odham Nation reservation is not merely a static representation of land; it is a dynamic, living document that encapsulates a rich and complex history, a vibrant and enduring identity, and a profound connection between a people and their desert homeland. To truly understand it is to glimpse the enduring spirit of the "Desert People" and to appreciate the power of a landscape to define and sustain a nation.