The Unseen Paths: A Traveler’s Guide to the Native American Maps of Forced Removal Routes

Forget quaint roadside attractions and picturesque vistas for a moment. Our journey today takes us through a landscape etched with profound sorrow, resilience, and an undeniable historical truth. We are tracing the Native American maps of forced removal routes, specifically the Trail of Tears, not as a casual tourist, but as a respectful pilgrim seeking understanding and connection to a pivotal, often painful, chapter of American history. This is a review of a "location" that spans thousands of miles, a journey through time and trauma, made navigable and tangible by the very maps that documented its horror and now guide its remembrance.

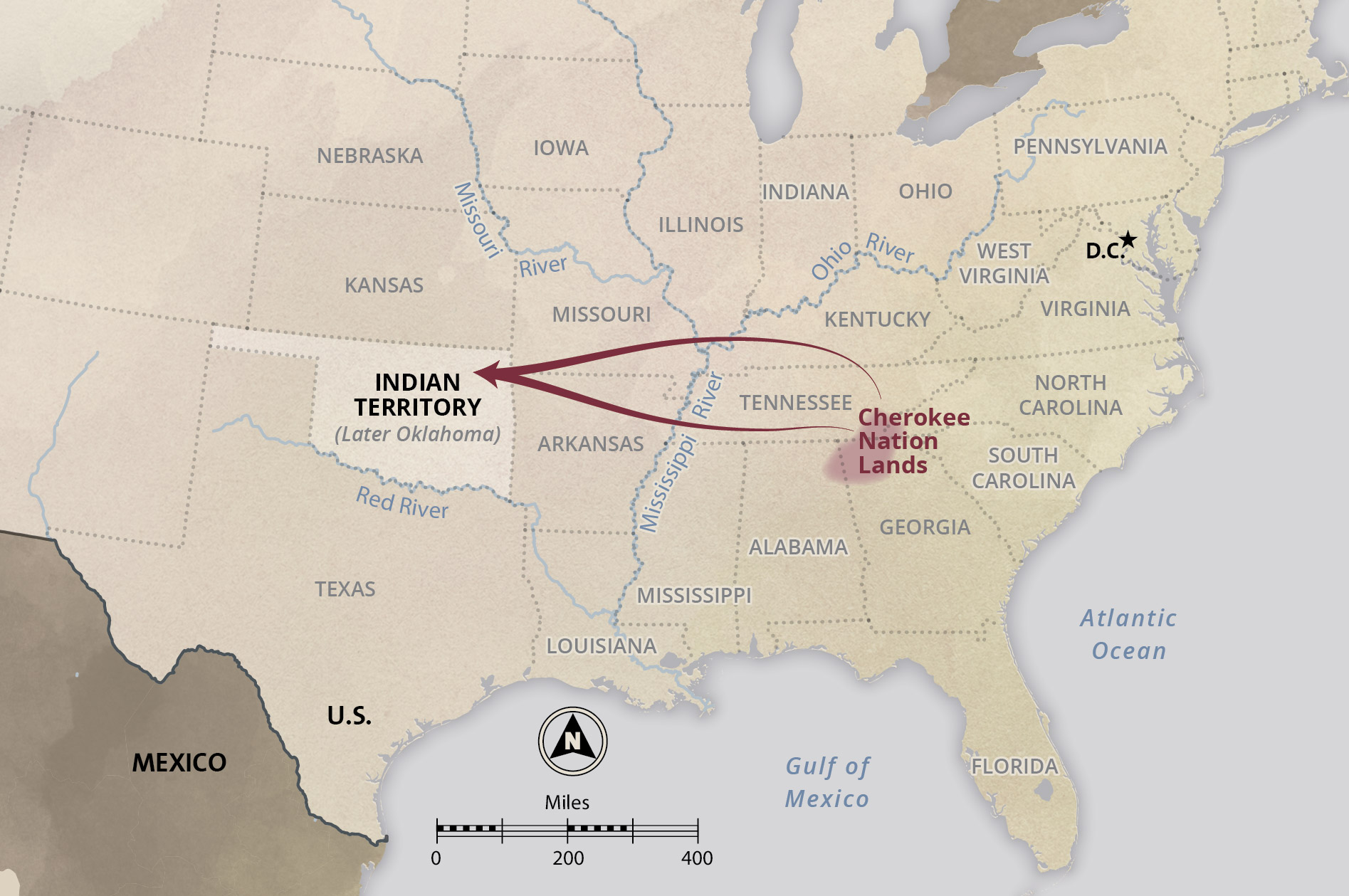

The "location" in question is the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, a sprawling network of routes stretching across nine states, officially managed by the National Park Service (NPS). It commemorates the forced removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations—collectively known as the "Five Civilized Tribes"—from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) during the 1830s. This isn’t a single destination; it’s an immersive, often somber, road trip through landscapes that bear witness to unimaginable suffering and enduring strength.

The Maps: From Tools of Displacement to Guides of Remembrance

At the heart of understanding this journey are the maps themselves. Initially, these were tools of empire: military surveys, land grants, and logistical charts drawn by the U.S. government and its agents to plan and execute the removal. These maps, cold and objective, laid out the routes, potential campsites, and river crossings, detailing the infrastructure needed to displace entire nations. They recorded the very paths where tens of thousands walked, sickened, and died.

Today, these historical documents are juxtaposed with modern interpretive maps, often incorporating Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology. These contemporary maps don’t just show the routes; they layer historical data, personal narratives, and cultural information, bringing the abstract lines to life. They highlight specific removal camps, grave sites, resource depletion points, and the natural features that both aided and hindered the forced march. Crucially, they also integrate the oral histories and traditional knowledge passed down through generations of Native American people, offering a perspective that the original government maps deliberately omitted.

For the traveler, these maps are more than navigational aids; they are portals to understanding. You won’t just see a line on a map; you’ll see the convergence of military strategy, human suffering, and the enduring spirit of the removed nations.

The Journey: What to Expect and Where to Go

Embarking on the Trail of Tears requires preparation, not just logistical, but emotional. This is not a lighthearted vacation. It is a pilgrimage, a journey of empathy and education.

1. The Eastern Terminus: Seeds of Removal and Cultural Loss (Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee)

- New Echota Historic Site, Calhoun, Georgia: Begin your journey here, at the capital of the Cherokee Nation prior to removal. Maps show this as the vibrant political and cultural heart of a sovereign nation. Walking the reconstructed grounds—the council house, print shop, Supreme Court building—you grasp the sophisticated society that was violently dismantled. The maps here illustrate the land cessions, the legal battles, and the political machinations that ultimately led to the Indian Removal Act. It’s a powerful, heartbreaking starting point, reminding you of what was lost.

- Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Cherokee, North Carolina: While the main removal routes bypassed much of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ lands (many evaded removal), this museum is essential for understanding Cherokee history, culture, and the context of the removal. Maps here often show the smaller, more localized removal efforts and the strategies of those who remained. It offers a vital contemporary Native American perspective.

- Red Clay State Historic Park, Bradley County, Tennessee: This was the last capital of the Cherokee Nation before their forced exodus. The maps show its strategic location, a temporary refuge after New Echota was seized. Here, you can walk the council grounds where the Cherokee Nation grappled with the impending removal, their final, desperate attempts to retain sovereignty. The emotional weight of this site is palpable, a place where a nation faced its darkest hour.

2. The Water Routes: A Different Kind of Suffering (Tennessee River, Mississippi River)

- Many of the removal routes involved significant water travel, particularly along the Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers. The maps of these routes often depict steamboat paths, flatboat movements, and the associated logistical nightmares.

- Port of Waterloo, Alabama: This small town on the Tennessee River was a significant embarkation point. As you stand by the river today, consulting historical maps, you can visualize the thousands of Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw people crowded onto boats, leaving their homes behind. The maps show the journey downriver, a stark contrast to the overland routes, but equally fraught with disease and despair.

- Trail of Tears State Park, Cape Girardeau, Missouri: Though outside the core removal states, this park marks a critical river crossing point on the Mississippi. Maps show the difficult winter crossings, often involving long waits for ferries in freezing conditions. The park’s interpretive center helps you understand the sheer scale of the operation and the suffering endured on these watery paths.

3. The Overland Routes: The Brutality of the March (Kentucky, Missouri, Arkansas)

- The majority of the Trail of Tears involved overland marches, often during the brutal winter of 1838-1839. These are the routes that maps show crisscrossing the landscape, sometimes following existing roads, sometimes through wilderness.

- Mantle Rock State Preserve, Livingston County, Kentucky: This iconic site offers a tangible connection to the overland route. Maps indicate Mantle Rock as a significant overnight stop for a large Cherokee detachment, trapped by ice on the Ohio River. The massive sandstone arch provided some shelter, but the hardship was immense. Walking the trail here, you can almost feel the presence of those who huddled beneath the rock, their hopes dwindling.

- Cherokee Trail of Tears Park, Hopkinsville, Kentucky: This park serves as a solemn memorial and includes actual gravesites of two Cherokee chiefs who died during the removal. The maps here often highlight specific encampments and grave locations, bringing a chilling reality to the journey.

- Various Segments in Arkansas and Missouri: The NPS website and local historical societies provide detailed maps of surviving segments of the original trail. These often run through rural areas, allowing for quiet reflection. Standing on these original paths, guided by a map that shows the very footsteps of suffering, is perhaps the most profound experience of the journey.

4. The Western Terminus: Resilience and Rebirth (Oklahoma)

- Cherokee Heritage Center, Tahlequah, Oklahoma: This is the cultural heart of the Cherokee Nation today and a vital final stop. Maps here show the "Indian Territory," the new lands allocated for the removed tribes. The center features a comprehensive museum, an ancient village, and a craft village. It’s a place of education, celebration of survival, and a testament to the resilience of Native American cultures. It allows you to see beyond the trauma and witness the vibrant living cultures that rebuilt their nations.

- Choctaw Nation Museum, Tuskahoma, Oklahoma: Similarly, this museum tells the story of the Choctaw removal and their subsequent rebuilding in Oklahoma. Each of the Five Tribes has a story of forced removal and resilience, and visiting these centers helps you understand the unique paths and triumphs of each nation.

The Deeper Meaning: Why Undertake This Journey?

Reviewing the Trail of Tears as a "location" isn’t about rating amenities or scenic beauty. It’s about confronting history, fostering empathy, and acknowledging the foundational injustices that shaped the American landscape. The maps, in their dual role as historical records and modern interpretive tools, are the key to unlocking this understanding.

Traveling these routes, guided by maps, transforms abstract historical facts into a visceral experience. You witness the scale of the forced removal, the strategic planning behind it, and the immense human cost. You walk where thousands walked, suffer where thousands suffered, and gain a profound appreciation for the resilience of the Native American nations.

This journey teaches us that history isn’t just in books; it’s embedded in the land. It encourages a deeper, more critical understanding of American identity and the ongoing legacy of colonialism. It’s a call to remember, to honor, and to support the sovereign Native American nations who continue to thrive despite immense adversity.

Practical Considerations for the Respectful Traveler

- Plan Ahead: The Trail of Tears is vast. Research specific sites you want to visit using the NPS website (www.nps.gov/trte) and state park resources.

- Respect Private Land: Many segments of the original trail cross private property. Stick to marked public access points, historic sites, and designated trails.

- Engage with Local Communities: Visit tribal museums and cultural centers. Support Native American-owned businesses. Learn about contemporary tribal life.

- Prepare for Emotional Impact: This journey can be deeply moving and emotionally challenging. Allow yourself time for reflection.

- Resources: Utilize NPS brochures, detailed maps (available online and at visitor centers), and audio guides to enhance your understanding.

In conclusion, the "location" of the Native American maps of forced removal routes is not just a place to visit; it is an education, a pilgrimage, and a testament to endurance. It is a journey that uses the very tools that documented a tragedy to illuminate a path toward remembrance, reconciliation, and a more complete understanding of our shared past. To traverse these paths, guided by their maps, is to bear witness, and in doing so, to ensure that the unseen paths are never forgotten.