The Contested Canvas: Journeying Through Navajo Nation with 20th-Century Maps

Forget the glossy brochures that only highlight scenic vistas. When you travel through the vast, breathtaking landscapes of the Navajo Nation (Diné Bikeyah), you’re not just witnessing natural beauty; you’re stepping onto a living map, a palimpsest where every mesa, every canyon, and every scattered hogan tells a story of profound 20th-century change. For the discerning traveler eager to understand the deeper layers of a place, embarking on a journey through this sovereign nation with the lens of historical Native American maps – or rather, the impact of mapping on Native American lands – offers an unparalleled, deeply moving experience. This isn’t just a trip; it’s an education in geopolitics, resilience, and the enduring power of land.

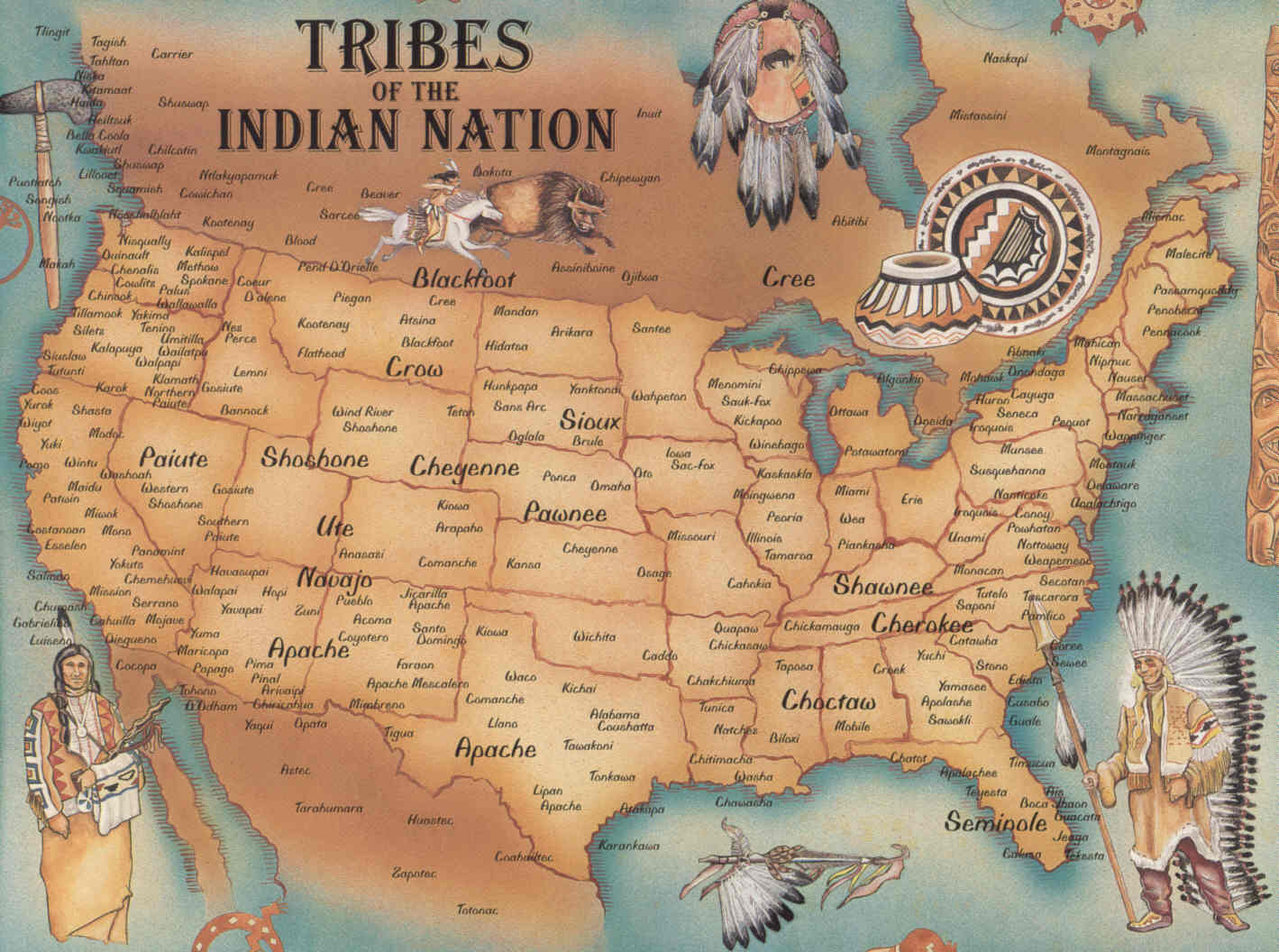

The concept of maps, for many of us, is purely functional: a tool for navigation, a guide to getting from A to B. But for Native American nations, especially throughout the turbulent 20th century, maps were weapons, battlegrounds, and ultimately, instruments of resistance and self-determination. They codified land loss, dictated resource extraction, and sometimes, with great effort, documented the reclamation of sovereignty. To review the Navajo Nation as a destination through this specific historical lens is to unlock a critical understanding of how colonial policies reshaped Indigenous territories, and how communities adapted, survived, and thrived amidst relentless pressure.

The Landscape as a Historical Document: A Primer on 20th-Century Changes

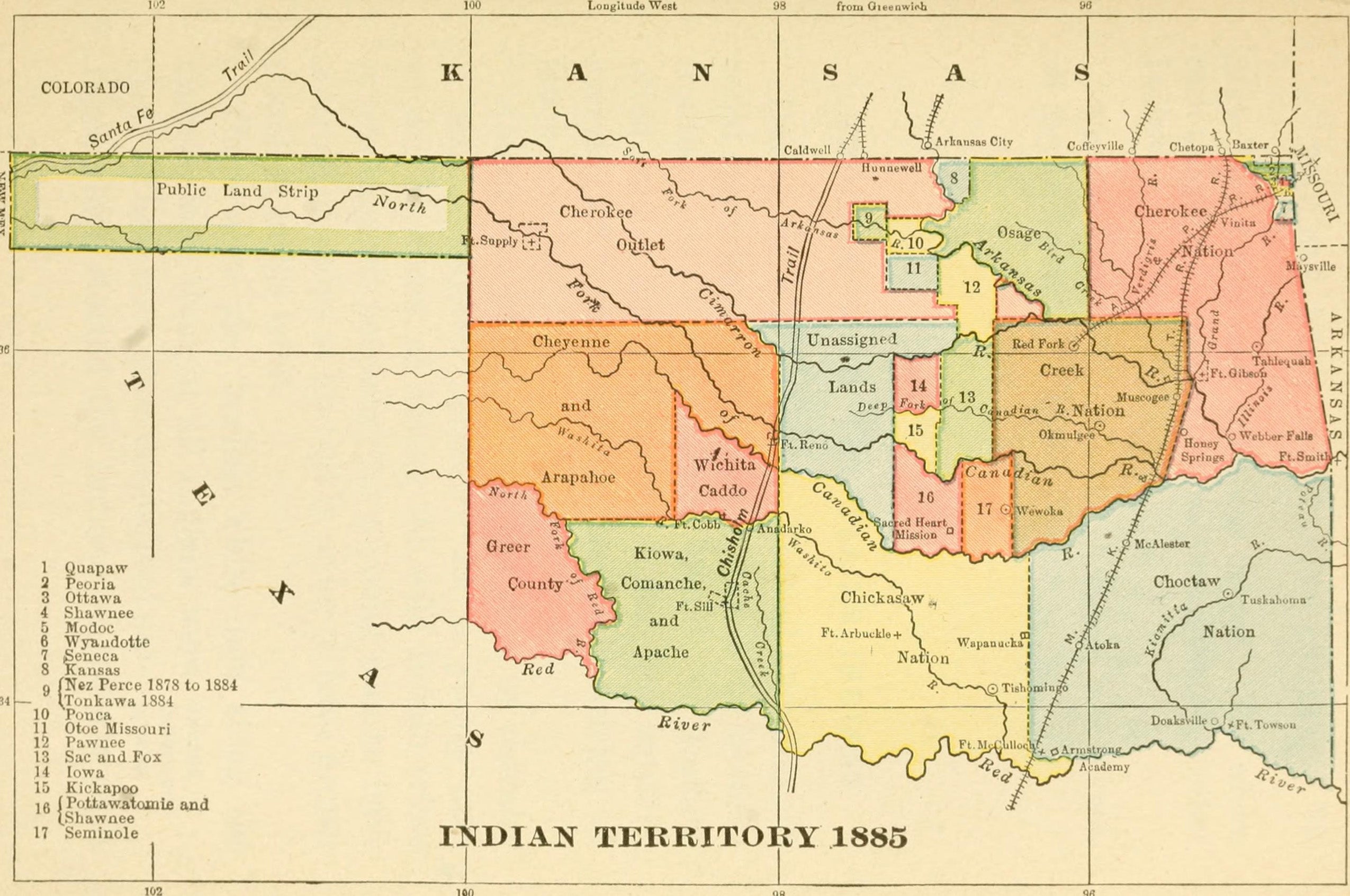

To truly appreciate the Navajo Nation as a "living map," one must first understand the historical forces that literally redrew the lines of Native American life in the 20th century. While the Navajo Nation largely avoided the most devastating effects of the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887, which parceled out communal tribal lands into individual ownership, it was by no means immune to other federal policies that profoundly impacted its borders, resources, and people.

The 20th century brought a new wave of challenges:

- Resource Exploitation: The mid-20th century saw a dramatic increase in the mapping and extraction of natural resources within reservation boundaries. Uranium, coal, oil, and natural gas were suddenly deemed vital for national security and economic growth. Maps became crucial in delineating mineral leases, often without full tribal consent or understanding of the long-term environmental and health consequences.

- Boundary Disputes and Land Transfers: While the Navajo Nation’s core territory remained largely intact, its periphery and surrounding lands were subject to various land exchanges, federal designations (like national parks or forests), and sometimes, forced relocations stemming from disputes with neighboring tribes, often exacerbated by federal intervention. The Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute, a tragic and complex issue, stands as a stark example of how mapped boundaries became tools of division and displacement.

- Infrastructure Development: As the nation grew, so did the need for roads, dams, power lines, and other infrastructure. These projects, while often bringing some benefits, frequently traversed or bisected tribal lands, impacting traditional land use and sacred sites. Maps for these projects were often drawn with little regard for Indigenous perspectives.

- Self-Determination Era: Towards the latter half of the century, the tide began to turn with the rise of the self-determination movement. Tribes began to assert more control over their lands and resources, utilizing their own mapping efforts, legal challenges, and political organizing to regain what was lost and to protect what remained. Maps, in this context, became tools of empowerment and sovereignty.

Navigating the Navajo Nation: What to See and How to See It

Visiting the Navajo Nation today, covering an area larger than West Virginia, is an immersion into these historical layers. Unlike a museum exhibit that presents maps behind glass, here, the maps are etched into the very earth.

1. The Uranium Belt: A Scars on the Landscape

- What to look for: As you drive through vast stretches of the eastern and central Navajo Nation, particularly around areas like Shiprock (Tsé Bitʼaʼí) and Monument Valley, look for subtle cues. While most active mines are long closed, the legacy of uranium mining is palpable. Abandoned structures, fenced-off areas, and the presence of remediation sites are physical manifestations of historical geological maps that pinpointed uranium deposits.

- The Map Connection: Imagine overlaying a 1950s USGS geological map, highlighting uranium veins, onto a modern road map. You’d see where countless prospectors and mining companies descended, leading to a boom that left behind a devastating legacy of cancer and environmental contamination. The absence of vibrant communities in certain areas, or the presence of isolated, struggling families, often correlates directly with these historical extraction sites.

- Traveler’s Insight: Seek out Diné (Navajo) cultural centers or museums that address this history. Local guides can often point out specific sites and share personal stories of families affected by the "yellow dirt," transforming an abstract map into a deeply human narrative.

2. The Navajo-Hopi Partitioned Lands: A Legacy of Division

- What to look for: Traveling in the heart of the Navajo Nation, particularly the areas bordering the Hopi Reservation, you encounter a landscape marked by a painful history of forced relocation. The "Joint Use Area" and its subsequent partition, leading to the relocation of thousands of Navajo and Hopi families, is a stark example of how mapped boundaries can tear communities apart. You might see subtle differences in housing styles, or even hear stories of families whose lands were bisected by arbitrary lines.

- The Map Connection: This is where maps become incredibly contentious. Federal maps from the mid-20th century, drawing lines across ancestral lands, directly led to the displacement. Understanding these maps, alongside the oral histories of those affected, reveals the political nature of cartography.

- Traveler’s Insight: This is a sensitive topic. Engage respectfully, perhaps by visiting cultural centers in areas like Window Rock (Tségháhoodzání) or exploring resources from the Navajo Nation Museum. Understanding the history of these lines helps contextualize the ongoing struggles for land rights and self-determination.

3. Resource Extraction (Coal & Oil): Industrial Footprints

- What to look for: In the northern and western parts of the Navajo Nation, particularly near Black Mesa or the Four Corners region, you might encounter large industrial operations: power plants, coal mines (some now decommissioned), and oil wells. These are direct results of resource maps that identified lucrative energy deposits.

- The Map Connection: Historical maps showing coal leases, pipeline routes, and power plant locations illustrate the immense scale of resource extraction. Modern maps, conversely, might show tribal initiatives for renewable energy, demonstrating a shift towards sustainable practices and a reclaiming of resource management.

- Traveler’s Insight: Consider the vastness of the energy infrastructure and reflect on its impact. How did these operations benefit (or harm) the local communities? What are the ongoing environmental concerns? This prompts a deeper understanding of economic sovereignty versus environmental stewardship.

4. The Enduring Cultural Landscape: Beyond the Lines

- What to look for: Amidst these historical scars, the resilience of Diné culture shines through. Traditional hogans, sheep herds, roadside vendors selling fry bread and jewelry, and the pervasive presence of the Navajo language (Diné Bizaad) are all testaments to an enduring connection to the land that transcends any mapped boundary. Sacred sites, often unmarked on conventional maps, are known through oral tradition and cultural knowledge.

- The Map Connection: This is where Indigenous mapping, or "counter-mapping," becomes vital. Traditional Diné knowledge maps are not about fixed, arbitrary lines, but about relationships, sacred sites, grazing routes, and seasonal movements. These maps are dynamic, embedded in storytelling and ceremony, offering a profound contrast to colonial cartography.

- Traveler’s Insight: Engage with local artisans, attend cultural events if permitted, and consider a guided tour with a Diné individual who can share insights into the spiritual and cultural landscape. This allows you to "read" the land through Indigenous eyes, recognizing its inherent value beyond mere resources or boundaries.

5. Modern Development & Self-Determination: Mapping Progress

- What to look for: Observe the modern infrastructure: schools, hospitals, tribal government buildings in Window Rock, and the burgeoning small businesses. These are indicators of ongoing self-determination efforts.

- The Map Connection: Contemporary tribal government maps showcase administrative districts, health services, educational facilities, and economic development zones. They reflect the Navajo Nation’s journey from federal wardship to a powerful, self-governing entity actively planning its future. These maps are symbols of agency, outlining how the Nation allocates resources and provides for its citizens.

- Traveler’s Insight: Acknowledge the incredible progress made despite historical challenges. Support local businesses, respect tribal laws and customs, and appreciate the vibrant, ongoing life of the Navajo people.

The Review: A Transformative Journey

To "review" the Navajo Nation as a destination through the lens of 20th-century Native American maps is to award it five stars for its profound educational value and the deeply moving experience it offers. It’s not a passive sightseeing trip; it’s an active engagement with history, politics, and culture.

Pros:

- Unparalleled Historical Insight: No other location so vividly illustrates the impact of 20th-century federal policies on Native American lands and lives.

- Breathtaking Scenery: The natural beauty is, of course, undeniable and provides a stunning backdrop to the historical narrative.

- Rich Cultural Immersion: Opportunities to connect with Diné culture, art, and language are abundant.

- Promotes Critical Thinking: Challenges conventional narratives of American history and fosters a deeper understanding of Indigenous sovereignty and resilience.

- Supports Indigenous Tourism: By engaging respectfully, travelers can directly contribute to the Navajo Nation’s economy.

Cons (or rather, Considerations):

- Requires Intentionality: This isn’t a "relaxing beach vacation." It demands an open mind, a willingness to learn, and respect for sensitive histories.

- Vast Distances: The Nation is huge; plan your travel carefully to maximize your experience.

- Limited Interpretive Signage: While some sites have information, much of the historical context requires prior research or a knowledgeable local guide. You won’t find a "map exhibit" at every turn; you’ll be reading the land itself.

Conclusion: The Land Remembers

Traveling through the Navajo Nation with an awareness of its mapped history transforms a scenic road trip into an profound journey of understanding. Every turn in the road, every distant structure, every vast, empty expanse resonates with the stories etched by 20th-century maps – maps that once sought to control, divide, and exploit. Yet, what ultimately emerges is a testament not to the power of lines on paper, but to the enduring spirit of the Diné people. The land remembers, and by seeking to understand its contested canvas, we as travelers gain not just knowledge, but a deeper respect for the living map that is the Navajo Nation. It’s an essential journey for anyone truly interested in the history and future of this continent.