>

Decoding the Taiga: A Journey Through Subarctic Native American Tribal Maps, History, and Identity

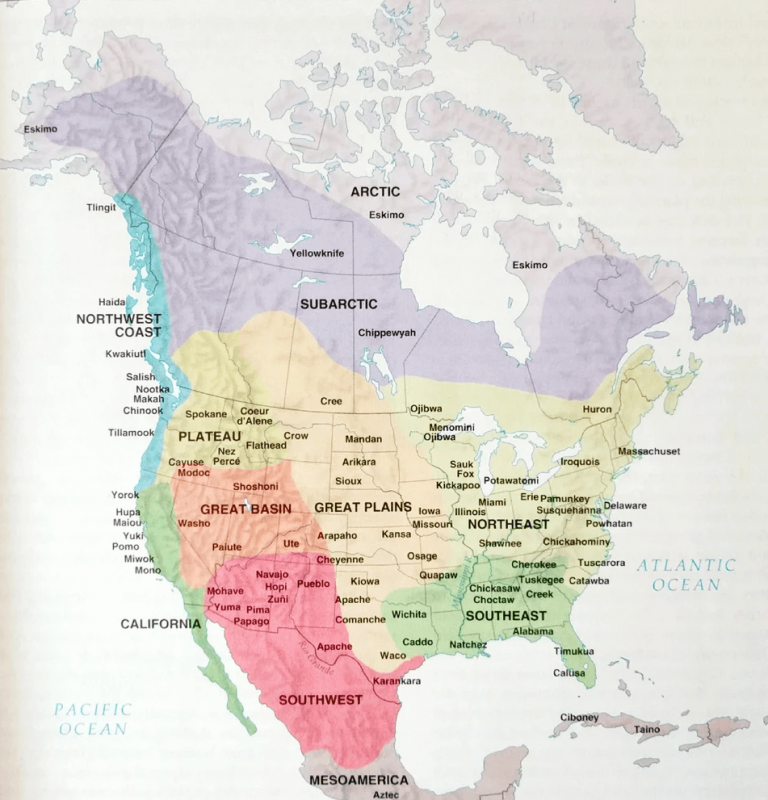

The map of Subarctic Native American tribes is more than just a cartographic representation; it is a living document, etched with millennia of history, profound cultural identity, and an enduring testament to human adaptation. For those drawn to the raw beauty of Canada and Alaska’s northern reaches, understanding these maps—and the peoples they represent—offers an indispensable key to appreciating a landscape that has profoundly shaped some of the world’s most resilient cultures. This article delves directly into the Subarctic tribal map, exploring its geographical context, the historical forces that shaped it, and the vibrant identities of the peoples who call this vast territory home.

Defining the Subarctic: Geography as Destiny

The Subarctic region of North America is an immense expanse, primarily encompassing most of Canada and large parts of interior Alaska, with a few extensions into the northernmost United States. It is a land dominated by the boreal forest (taiga), a dense belt of coniferous trees like spruce, fir, and pine, interspersed with vast networks of lakes, rivers, and wetlands. To the north, the boreal forest gradually transitions into the treeless tundra, while to the south, it meets the temperate forests of the Great Lakes region or the plains.

This geographical reality is paramount to understanding the indigenous groups of the Subarctic. The climate is characterized by long, intensely cold winters and short, cool summers. Permafrost underlies much of the ground, limiting agriculture and dictating patterns of movement. Resources, though plentiful in specific seasons, are widely dispersed. Consequently, Subarctic peoples developed highly mobile, specialized hunting, fishing, and gathering lifeways. Their traditional territories, as depicted on historical and contemporary maps, reflect these ecological imperatives: they are vast, often overlapping, and defined by crucial resource areas like caribou migration routes, salmon spawning rivers, and prime trapping grounds. These are not static, fixed borders in the European sense, but fluid zones of influence, usage, and deep ecological knowledge.

The Linguistic Tapestry: Two Major Threads

At the heart of interpreting any tribal map of the Subarctic lies its linguistic landscape, dominated by two major language families: Athabaskan (also known as Dene) and Algonquian. These families represent deep historical divisions and migrations that have shaped the cultural contours of the region for thousands of years.

The Athabaskan (Dene) Peoples: Predominantly occupying the western and central Subarctic, from Alaska through Yukon, the Northwest Territories, and into the Canadian Prairies, the Dene are the most numerous and geographically widespread of the Subarctic groups. The term "Dene" itself means "people" in many of their languages, reflecting a shared linguistic ancestry despite diverse cultures.

Key Athabaskan groups include:

- Gwich’in: Residing in northeastern Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories, renowned for their deep connection to the Porcupine Caribou Herd.

- Deg Hit’an (Ingalik): Along the lower Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers in Alaska.

- Hän: In the Yukon and Alaska along the Yukon River.

- Kaska: In northern British Columbia and Yukon.

- Tłı̨chǫ (Dogrib): In the Northwest Territories, between Great Slave Lake and Great Bear Lake.

- Chipewyan (Dënesųłı̨né): Spanning northern Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Alberta, known for their caribou hunting traditions.

- Slavey (Dene Tha’, South Slavey, North Slavey): Along the Mackenzie River in the Northwest Territories and northern British Columbia.

- Sahtu Dene: Around Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories.

- Sekani, Tahltan, Tagish, Northern Tutchone, Southern Tutchone: Various groups primarily in British Columbia and Yukon.

The Algonquian Peoples: Dominating the eastern Subarctic, from the Great Lakes eastward through Quebec and Labrador, the Algonquian family represents another ancient and expansive linguistic group.

Key Algonquian groups in the Subarctic include:

- Cree: One of the largest Indigenous groups in Canada, the Cree are incredibly diverse, with Subarctic groups including the Woodland Cree and Swampy Cree across Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec. They were instrumental in the fur trade due to their strategic locations and extensive knowledge of the land.

- Ojibwe (Anishinaabe): While many Ojibwe groups reside further south, northern bands extend into the Subarctic regions of Ontario and Manitoba, sharing many cultural traits with their Subarctic neighbours.

- Innu (Montagnais-Naskapi): Occupying a vast territory in Quebec and Labrador (known as Nitassinan), the Innu are historically divided into the more settled Montagnais and the more nomadic Naskapi, both deeply connected to the caribou.

These linguistic distinctions are often the primary markers on historical maps, delineating broad cultural areas rather than rigid national borders. They highlight shared heritage, but also internal diversity within each language family.

Pre-Contact Societies: A Legacy of Ingenuity and Adaptation

For thousands of years before European contact, Subarctic peoples thrived in their challenging environment, developing sophisticated knowledge systems and material cultures. Their maps, often held in memory and transmitted through oral traditions, were mental blueprints of seasonal movements, resource locations, and ancestral narratives.

Life revolved around the seasonal pursuit of game. Caribou, moose, and beaver were central to their existence, providing food, clothing, tools, and shelter. Fishing for salmon, whitefish, and pike was also crucial, especially in regions with abundant waterways. Small game, migratory birds, and various berries and roots supplemented their diet. This required a deep understanding of animal behaviour, plant cycles, and weather patterns – a knowledge base unparalleled in its depth.

Technology was honed for mobility and efficiency:

- Birchbark canoes: Lightweight and versatile, essential for summer travel on the extensive river and lake systems.

- Snowshoes and toboggans: Indispensable for winter travel, allowing passage over deep snow and transport of goods.

- Woven snares and traps: For small game.

- Specialized hunting tools: Such as caribou fences and elaborate fishing weirs.

Social structures were typically egalitarian, focused on kinship and small, mobile family groups or bands. Decisions were often made by consensus, with respect for elders and skilled hunters. Spirituality was deeply intertwined with the land and its creatures, with oral traditions, ceremonies, and storytelling playing a vital role in transmitting knowledge, values, and history across generations. The resilience of these pre-contact societies laid the foundation for their endurance through subsequent periods of profound change.

The Fur Trade Era: Transformative Encounters

The arrival of European fur traders from the 17th century onwards marked a dramatic turning point. Companies like the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company pushed deep into the Subarctic, establishing trading posts that fundamentally altered Indigenous economies and societies. Maps from this era begin to show trading routes, forts, and areas of influence, reflecting European commercial interests superimposed on Indigenous territories.

Indigenous peoples, with their unparalleled knowledge of the land and trapping skills, became indispensable partners in the fur trade. They traded beaver pelts, moose hides, and other furs for European goods such as metal tools, firearms, blankets, and foodstuffs. While initially beneficial, the trade quickly led to dependency. Traditional hunting patterns shifted from subsistence to commercial trapping, leading to resource depletion in some areas. European diseases, against which Indigenous populations had no immunity, decimated communities, causing immense social disruption and loss of traditional knowledge. The fur trade also inadvertently introduced new power dynamics and sometimes exacerbated inter-tribal conflicts over trapping territories.

Despite these challenges, Indigenous peoples maintained significant agency. They acted as guides, interpreters, and key suppliers, demonstrating their adaptability and strategic acumen in navigating this new economic landscape. Many Métis communities, with mixed Indigenous and European ancestry, emerged from this era, developing their own distinct culture and identity, often acting as intermediaries in the trade.

The Era of Colonization and Assimilation: Erasure and Resistance

As European powers consolidated their hold on North America in the 19th and 20th centuries, the Subarctic peoples faced intensified pressures of colonization. In Canada, the creation of the Dominion and subsequent policies led to the signing of the Numbered Treaties across much of the Subarctic. While intended by the Crown to be agreements of shared land use, they were often understood very differently by Indigenous signatories and subsequently interpreted to dispossess Indigenous peoples of their land and sovereignty.

Government policies, particularly the infamous Indian Act in Canada and similar legislation in the United States, sought to control, manage, and assimilate Indigenous populations. The devastating Residential School system in Canada and Boarding Schools in the US forcibly removed children from their families, languages, and cultures, inflicting intergenerational trauma that continues to impact communities today. Maps from this period often reflect the imposition of reserves, often small and inadequate, on traditional territories, and the vast swaths of land designated as "Crown Land" or "unoccupied," effectively erasing Indigenous presence.

The relentless pursuit of natural resources—mining, oil and gas, forestry, and hydroelectric development—further encroached upon traditional territories, often without Indigenous consent, leading to environmental degradation and ongoing land disputes. This era was one of profound loss, but also of persistent resistance and the quiet safeguarding of cultural identity and knowledge against overwhelming odds.

Resurgence and Self-Determination: Reclaiming the Map

Despite the profound traumas of colonization, Subarctic Native American peoples have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. The latter half of the 20th century and the 21st century have seen a powerful resurgence of Indigenous rights movements, cultural revitalization, and the pursuit of self-determination.

This era is marked by:

- Comprehensive Land Claims: Modern treaties and land claims agreements, such as the Inuvialuit Final Agreement, the Gwich’in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement, and the Tłı̨chǫ Agreement, have legally recognized Indigenous title and governance over significant portions of their traditional territories. These agreements are literally redrawing the map of the Subarctic, establishing Indigenous-led governments and economic development initiatives.

- Cultural and Linguistic Revitalization: Communities are actively working to reclaim and strengthen their languages, oral traditions, ceremonies, and traditional arts. Language immersion programs, cultural camps, and community-led initiatives are vital in healing intergenerational trauma and fostering renewed pride in identity.

- Political Advocacy: Indigenous nations are increasingly asserting their rights on the national and international stage, advocating for environmental protection, social justice, and respect for their inherent sovereignty.

Today, maps created by and with Indigenous communities are powerful tools for asserting land rights, managing resources, and planning for a self-determined future. These maps often incorporate traditional place names, historical land use data, and cultural sites, offering a rich, Indigenous perspective that contrasts sharply with colonial cartography.

Interpreting the Map Today: Beyond Lines on Paper

To truly understand a Subarctic Native American tribes map today is to recognize it as a dynamic document, a reflection of both ancient connections and ongoing struggles. It is not merely a guide to where people "were," but where they "are" and "are going."

For the traveler and history enthusiast, these maps offer an invitation to:

- Appreciate the scale of adaptation: Witness how human ingenuity thrived in one of the planet’s most challenging environments.

- Respect Indigenous sovereignty: Recognize that the vast lands of the Subarctic are not empty wilderness, but homelands with deep histories and living cultures.

- Understand ongoing issues: Learn about the impacts of climate change, resource extraction, and the continuing efforts towards reconciliation and self-governance.

- Engage respectfully: If visiting these territories, seek out Indigenous-led tourism initiatives, support local businesses, and learn about the local protocols and customs.

The lines and colors on a Subarctic tribal map represent thousands of years of human history, a profound connection to the land, and an unwavering spirit of resilience. They tell stories of survival, innovation, loss, and resurgence. By engaging with these maps and the rich histories they encapsulate, we gain not just geographical knowledge, but a deeper understanding of human identity, adaptation, and the enduring power of culture in the face of profound change.

>