Reclaiming the Map: Experiencing Colonial Forts Through Indigenous Cartography

Forget the usual tour of colonial forts, where narratives often center solely on European military strategy and settler expansion. Imagine instead, traversing these historic landscapes with a different kind of map in hand—not the familiar grid lines and compass roses of European cartography, but the intricate, nuanced, and deeply strategic spatial understandings of the Indigenous peoples who lived there long before, and often alongside, these imposing structures. This isn’t a review of a single fort, but an invitation to a transformative way of experiencing any early colonial fort site, from the weathered stone bastions of New England to the earthen ramparts of the Great Lakes, by actively seeking out the Indigenous perspectives that shaped their very existence and eventual demise.

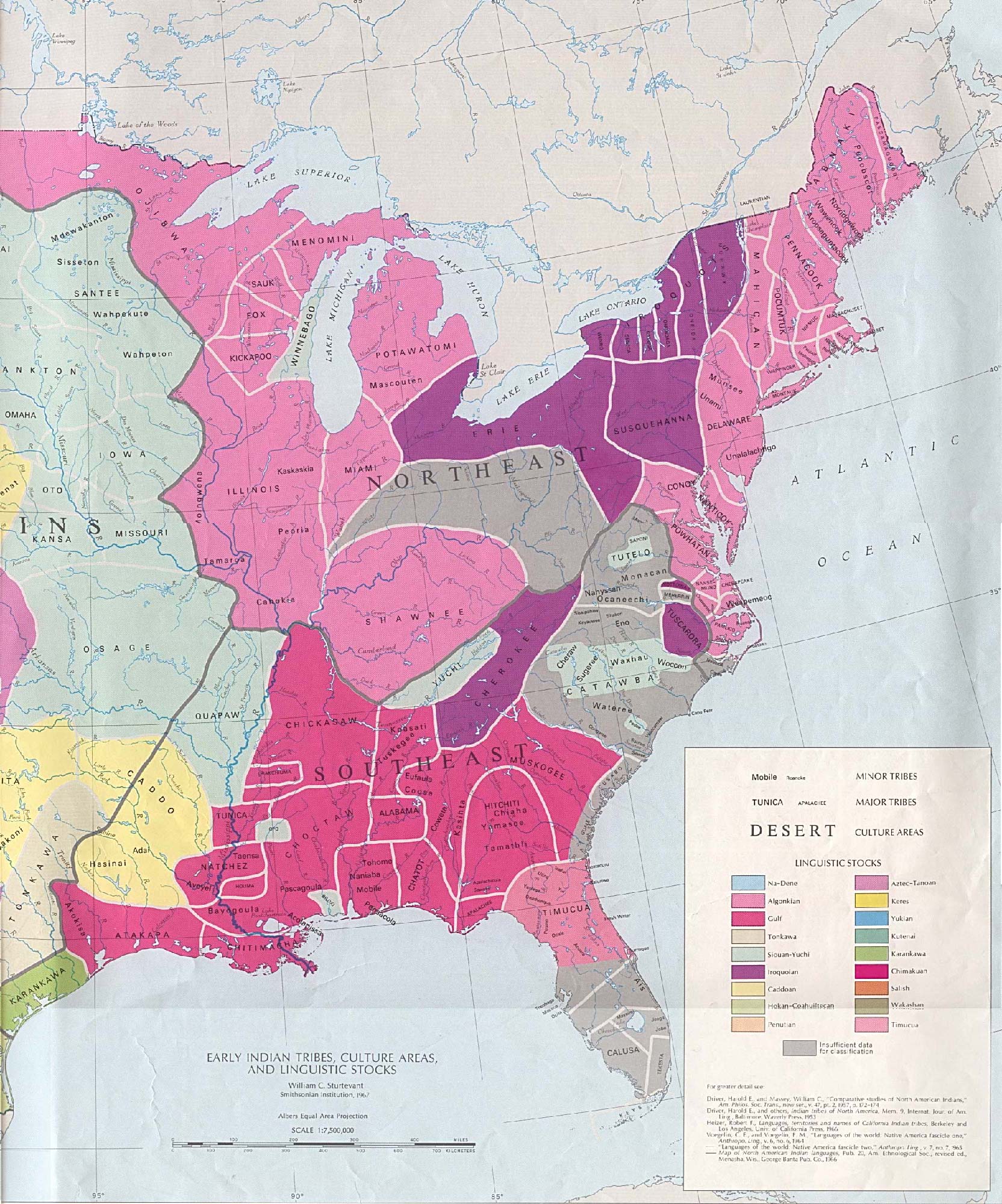

The "location" we are exploring is not just a physical place, but a historical intersection: the point where European colonial ambitions, manifested as forts, met the sophisticated geographic knowledge and strategic insights of Native American nations. For centuries, Indigenous peoples navigated, mapped, and understood these territories with a precision that often surpassed early European efforts. Their maps—whether etched into birchbark, drawn in sand, painted on hides, or conveyed through oral traditions and mnemonic devices—were vital tools for diplomacy, trade, war, and survival. These weren’t mere artistic renderings; they were repositories of intelligence, detailing not only topography and waterways but also resource locations, tribal boundaries, sacred sites, and crucial pathways, including those leading to and from colonial strongholds.

Consider the early French and British forts scattered across what is now the northeastern United States and southeastern Canada—places like Fort Ticonderoga, Fort William Henry, Fort Niagara, or the remnants near early settlements like Jamestown or Plymouth. These were not built in a vacuum. Their locations were often dictated by existing Indigenous trade routes, river systems, portages, and strategic overlooks—knowledge directly or indirectly gleaned from Native inhabitants. Crucially, the intelligence gathered by Indigenous scouts and warriors, and often communicated through their own mapping traditions, profoundly influenced how these forts were built, defended, attacked, or circumvented.

For the modern traveler, understanding this dynamic opens up a richer, more complex narrative. When you stand on the grounds of a colonial fort today, try to peel back the layers of familiar history. Ask yourself: how would a Mohawk scout have viewed this fort? What information would a Lenape cartographer have prioritized if tasked with depicting its vulnerabilities? How would a Narragansett leader have used their knowledge of the surrounding landscape to either avoid or assault this European outpost?

The challenge, and indeed the adventure, lies in the fact that many existing fort interpretations still prioritize the colonial narrative. Native American perspectives, if present, are often relegated to side notes or presented as reactions to European actions, rather than as active, independent forces. This is where the traveler’s active engagement becomes crucial. You are not just visiting a site; you are becoming an amateur historical detective, seeking out the less visible stories.

To truly engage with Native American maps of early colonial forts, you need to cultivate a specific way of seeing. Start by researching the specific Indigenous nations whose ancestral lands these forts occupy. For Fort Ticonderoga in New York, that would be the Abenaki, Mohawk, and other Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy nations. For Jamestown, it’s the Powhatan Confederacy. Understanding their cultures, their geopolitical relationships at the time, and their methods of conveying spatial information is foundational. Websites of tribal nations, university archives, and specialized historical societies often provide invaluable resources.

When you arrive at a fort site, look beyond the reconstructed palisades and barracks. Pay attention to the natural landscape: the rivers, lakes, hills, and forests. These were the primary "maps" for Indigenous peoples. They understood water currents, seasonal game migrations, and the fastest routes through dense terrain in ways Europeans often struggled to grasp. A fort positioned at a strategic choke point on a river, for example, might seem like an obvious European choice, but it was almost certainly a choke point already recognized and utilized by Native traders and warriors for generations.

Seek out any exhibits that touch upon Native American presence, even if they don’t explicitly mention maps. Look for artifacts—tools, weapons, pottery shards—that indicate long-term Indigenous occupation of the area. Read the plaques carefully for mentions of alliances, conflicts, or trade relationships with Native peoples. Often, European maps from the period include features drawn from Indigenous knowledge, sometimes directly by Native informants for European cartographers. These "hybrid maps" are fascinating windows into shared, yet often contested, spatial understandings. While original Native maps of specific forts are rare in their original Indigenous form (as many were ephemeral or oral), European copies or interpretations of Native information do exist in archives and sometimes feature in museum exhibits. For example, some early French maps of the Great Lakes region show details that could only have come from Ojibwe or Huron guides.

Consider the story of Fort Duquesne (later Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh). Its strategic location at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers, forming the Ohio, was not an accidental European discovery. This "Forks of the Ohio" was a vital hub for Indigenous trade and travel long before the French arrived. Native American "maps" of this area, though likely not on paper, were deeply ingrained in the collective memory and oral traditions of nations like the Shawnee, Delaware, and Haudenosaunee, who used it as a crossroads. Visiting the Point State Park in Pittsburgh today, one can reflect on this multi-layered history, imagining the various peoples who recognized its strategic value.

Another powerful way to connect with this history is to visit nearby tribal cultural centers or museums, if available. These institutions offer authentic Indigenous perspectives on their history, land, and interactions with colonial powers. They might display traditional tools, art, and historical documents that speak to their cartographic traditions and strategic knowledge. Engaging with these resources provides a crucial counterpoint to colonial narratives and helps to re-center Indigenous voices.

The experience of approaching colonial forts through this Indigenous cartographic lens is profoundly enriching. It transforms a visit from a passive consumption of history into an active intellectual and emotional journey. You begin to see the landscape as a dynamic palimpsest, with layers of meaning and power struggles inscribed upon it. The forts, rather than standing as isolated monuments to European triumph, become markers in a much broader, more complex narrative of negotiation, conflict, and adaptation between diverse peoples.

You’ll find yourself asking deeper questions: How did Native intelligence networks operate around these forts? How did Indigenous leaders use their knowledge of the terrain to outmaneuver or blockade European forces? What impact did the construction of these forts have on Indigenous hunting grounds, sacred sites, and traditional travel routes? By seeking answers to these questions, you are not just learning history; you are re-framing it.

This approach also highlights the incredible resilience and strategic brilliance of Native American nations. They were not merely passive victims of colonial expansion but active agents, utilizing their profound knowledge of the land—their inherent "maps"—to defend their territories, forge alliances, and navigate an increasingly complex world. Their cartographic understanding was a form of power, often underestimated by Europeans, yet instrumental in shaping the course of early colonial conflicts.

The journey of re-mapping colonial forts through Indigenous eyes is not always easy. It requires effort, critical thinking, and a willingness to challenge established narratives. But the rewards are immense. It offers a more complete, honest, and respectful understanding of America’s foundational history. It allows you to connect with the land and its past inhabitants in a way that transcends the typical tourist experience. So, on your next trip to an early colonial fort, arm yourself with curiosity, an open mind, and a willingness to look beyond the palisade—to see the fort not just as a European outpost, but as a critical point on a much older, Indigenous map of power, strategy, and enduring connection to the land. This shift in perspective transforms the visit from a simple historical tour into a profound engagement with the layered and living history of this continent.