For the traveler obsessed with the tangible echoes of history, where lines on a map transform into the very ground beneath your feet, the Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site in Republic, Kansas, is not merely a destination—it is an immersion. This isn’t a place for casual browsing; it’s a profound journey into a past often overlooked, a place where the cartographic representations of the Pawnee Nation come alive with an arresting clarity. This review eschews pleasantries and dives straight into why this site is indispensable for anyone seeking to understand the deep history of the Great Plains through the lens of Indigenous geography.

The Site: A Living Map of Pawnee Life

Located in north-central Kansas, near the Nebraska border, the Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site preserves the remains of a significant 19th-century Kitkehahki (Republican) Pawnee village. What makes this site so compelling, and so directly relevant to historical maps, is its physical manifestation of a mapped landscape. Before European contact, Indigenous peoples across North America possessed sophisticated spatial knowledge, often articulated through oral traditions, mnemonic devices, and even physical markings on the land itself. European and American cartographers, upon encountering these vast territories, began to superimpose their own systems, often relying on Indigenous guides and their knowledge of rivers, trails, and village locations. This site represents one such location, a point on countless historical maps, now made real.

The core of the site consists of a modern visitor center and museum, an excavated lodge site protected by a concrete shell, and a reconstructed earthlodge. But the real "map" is the land itself: the subtle depressions in the prairie grass that mark the locations of dozens of other earthlodges, the faint outlines of defensive earthworks, and the expansive views that once defined the Pawnee world.

Stepping into the Map: The Earthlodge Experience

The reconstructed earthlodge is the undeniable centerpiece and the most direct sensory link to the Pawnee past. Walking from the modern visitor center across the short path, the lodge rises from the prairie, a domed, sod-covered structure that blends seamlessly with the landscape. It’s a powerful visual, immediately grounding the visitor in the architectural ingenuity and environmental adaptation of the Pawnee.

Entering the lodge is like stepping into a three-dimensional map point. The interior is cool, dark, and surprisingly spacious. Light filters through the smoke hole at the apex, illuminating the central hearth. The perimeter is lined with sleeping platforms, and storage pits are dug into the floor. Here, the abstract concept of "Pawnee village" found on a historical map ceases to be an academic exercise. You are standing where families lived, cooked, told stories, and performed ceremonies. You can almost hear the rustle of buffalo hide, the murmur of conversation, the crackle of fire.

This immersive experience directly informs our understanding of historical maps. Early European maps of the Great Plains often show vague "Indian villages" or "Pawnee settlements" as simple dots or symbols. Visiting this lodge allows one to populate those dots with life, to understand the scale of community, and to appreciate the sophisticated engineering that went into creating such a dwelling. It provides context for the spatial organization that would have been critical for tribal cohesion, defense, and resource management—all elements implicitly or explicitly represented on maps.

The Cartographic Context: Pawnee Territory and Its Depiction

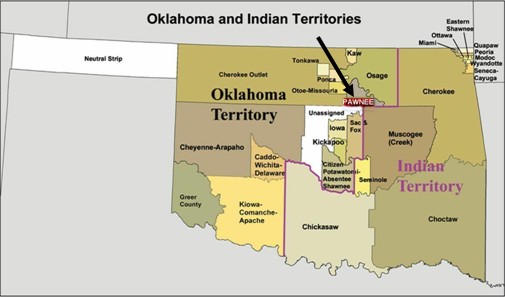

The Pawnee Nation, a confederation of four distinct bands (Chaui, Kitkehahki, Pitahawirata, and Skidi), once held vast territories across what is now Nebraska and Kansas. Their semi-sedentary lifestyle involved seasonal cycles: cultivating corn, beans, and squash in permanent earthlodge villages along rivers for part of the year, and then embarking on extensive buffalo hunts across the open plains. This dual existence is crucial to understanding their "maps."

- Pawnee’s Internal Maps: While few physical maps drawn by the Pawnee themselves survive in the Western sense, their oral traditions, sacred bundles, and deep ecological knowledge constituted a rich internal map. They knew every buffalo trail, every water source, every sacred hill, every ancestral village site. Their understanding of trade routes, inter-tribal boundaries, and resource availability was a complex mental cartography that guided their movements and defined their world. This site, as one of their major agricultural centers, was a critical node in that internal map.

- European and American Maps: From the 17th century onwards, French, Spanish, and later American explorers and cartographers began to chart the interior of the continent. Early maps often depicted "Padouca" (a general term often applied to Plains tribes, including sometimes the Pawnee) or "Pawnee" territory as large, undefined regions. As expeditions like those of Zebulon Pike (who visited a Pawnee village in 1806, though not this specific one) ventured deeper, maps became more detailed, marking rivers, trails, and specific village locations. The Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site represents one such "dot" that began to appear with increasing precision on maps of the early to mid-19th century.

- Archaeological Maps: Perhaps the most direct link to maps at the site itself comes from modern archaeology. Extensive archaeological surveys and excavations have created incredibly detailed maps of the village layout. These maps show the precise locations of over 40 earthlodges, defensive ditches, and activity areas. They reveal the organized, planned nature of the village—a testament to communal effort and strategic thinking. Walking the grounds, observing the subtle depressions, is to read an archaeological map with your feet, tracing the ghost of a vibrant community.

Historical Significance: A Point of Contact and Change

This particular village, occupied by the Kitkehahki band, is believed to be the last known earthlodge village of the Pawnee in Kansas, occupied until about 1830. Its abandonment was part of a larger pattern of displacement, disease, and pressure from westward expansion and rival tribes (especially the Cheyenne and Arapaho, armed by traders). The site thus becomes a poignant marker on the map of Indigenous removal and the shrinking of traditional territories.

The museum exhibits at the visitor center excel at placing the site within this broader historical narrative. Artifacts recovered from the village—pottery shards, stone tools, trade goods like glass beads and metal—tell stories of daily life, trade networks, and early interactions with European newcomers. These artifacts are tangible pieces of the history that maps attempt to condense into lines and labels. They give substance to the cultural exchange and eventual conflict that reshaped the map of the continent.

Why Visit: Beyond the Lines on the Map

For the discerning traveler, the Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site offers more than just a historical lesson; it offers a profound meditation on place, identity, and the power of the land.

- Immersive Learning: It’s one thing to read about earthlodges or see them depicted on maps; it’s another to stand inside one, feeling the weight of history and the ingenuity of its construction.

- Connection to Landscape: The vast, open prairie surrounding the site is integral to the Pawnee story. It forces a contemplation of the scale of their former territory and the impact of its loss. The landscape itself becomes a living map, showing where buffalo roamed, where rivers offered sustenance, and where the sky met the earth in an unbroken horizon.

- Understanding Cartographic Evolution: The site helps to demystify how maps are made and interpreted. It demonstrates how abstract symbols on a paper map represent real places, real people, and real histories. It highlights the transition from Indigenous spatial knowledge to European cartographic conventions and the complexities inherent in that process.

- Cultural Empathy: Engaging with the site fosters a deeper understanding and empathy for the Pawnee people. It moves beyond stereotypes, revealing a sophisticated, resilient culture that thrived on the plains for centuries before dramatic changes irrevocably altered their world.

Practicalities for the Traveler

- Location: The site is remote, located in Republic, Kansas, a small community in the northern part of the state. It requires intentional travel, but the journey through the rolling Kansas prairie is part of the experience, offering a glimpse into the landscape the Pawnee knew.

- Facilities: The visitor center is well-maintained with clean restrooms, a small gift shop, and informative exhibits.

- Time Commitment: Plan for at least 1.5 to 2 hours to fully explore the visitor center, the reconstructed lodge, and walk the outdoor grounds. More if you wish to linger and reflect.

- Best Time to Visit: Spring and fall offer pleasant temperatures. Summer can be hot, and winter can be very cold, though the site is open year-round (check specific hours).

- Accessibility: The visitor center and reconstructed lodge are generally accessible. The outdoor trails are mostly grass and can be uneven.

Conclusion: A Mapped Memory, Made Real

The Pawnee Indian Village State Historic Site is not just a collection of artifacts or a single reconstructed dwelling; it is a meticulously preserved fragment of a vast, complex, and resilient culture. For anyone interested in the history of the Great Plains, Indigenous studies, or simply the powerful narrative of how people live on and interact with the land, this site is a profound experience. It challenges us to look beyond the lines and labels of historical maps and to see the human stories, the ingenuity, the struggles, and the enduring spirit that they represent. It is, in essence, a map brought to life, inviting the traveler to walk through the echoes of a past that continues to shape our present.