Unveiling the Ancient Tapestry: The Passamaquoddy Traditional Lands Map of Maine

Maine, a state synonymous with rugged coastlines, dense forests, and picturesque lighthouses, holds a deeper, older story etched into its very landscape. Beneath the surface of familiar towns and tourist destinations lies the profound, enduring legacy of the Passamaquoddy Tribe, whose traditional lands map is not merely a geographic outline, but a living testament to thousands of years of history, identity, and an unbreakable connection to place. For any traveler or history enthusiast seeking to truly understand Maine, acknowledging and appreciating the Passamaquoddy’s ancestral territory is not just an educational exercise, but a vital step towards respectful engagement with the land and its original stewards.

The Passamaquoddy, or Peskotomuhkati in their own language, are one of the five nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy—the "People of the Dawnland"—who have inhabited what is now known as Maine and Atlantic Canada for at least 12,000 years. Their name, derived from Peskotomuhkatik, translates to "people of the pollock spearer," a direct reference to their traditional reliance on fishing, particularly for pollock, in the rich tidal waters of Passamaquoddy Bay. Their traditional territory, Peskotomuhkatik, encompasses a vast and ecologically diverse region, far exceeding the boundaries of their modern-day reservations at Motahkomikuk (Indian Township) and Sipayik (Pleasant Point).

The Living Map: Beyond Modern Borders

To visualize the Passamaquoddy traditional lands map is to imagine a dynamic, interconnected ecosystem rather than static lines on paper. This ancestral territory primarily centers around the St. Croix River (known as Schoodic or Skutik to the Passamaquoddy), which historically marked a central artery for their communities, stretching from its headwaters deep in the interior forests to its mouth at Passamaquoddy Bay, emptying into the vast Bay of Fundy.

Their domain extended eastward along the coast of what is now Maine, reaching into southwestern New Brunswick, Canada. Inland, it encompassed the intricate network of lakes, rivers, and dense woodlands that define eastern Maine. This included significant bodies of water like Big Lake (Chiputneticook Lake) and its surrounding watersheds, crucial for salmon, eel, and other freshwater resources. The coastal areas, with their powerful tides and abundant marine life, provided shellfish, seals, porpoises, and various fish, while the interior forests offered deer, moose, bear, and a wealth of plants for food, medicine, and materials.

This "map" was not a fixed, political boundary, but a living, breathing territory defined by seasonal movements, resource availability, and a profound understanding of the natural world. The Passamaquoddy practiced a sophisticated form of sustainable living, moving between coastal camps in the summer and interior hunting grounds in the winter. Their trails crisscrossed the landscape, connecting villages, resource sites, and trade partners, forming an intricate web of knowledge and occupation. Every stream, mountain, and bay had a name, a story, and a purpose, deeply embedded in their language and oral traditions.

A History Forged in the Dawnland

The history of the Passamaquoddy on these lands is one of remarkable resilience, adaptation, and unwavering cultural persistence in the face of immense challenges.

Pre-Contact Prosperity: For millennia before European arrival, the Passamaquoddy lived in harmony with their environment, developing complex social structures, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated technologies for hunting, fishing, and gathering. They were part of extensive trade networks with other Wabanaki nations and beyond, exchanging goods like furs, tools, and foods. Their governance was based on consensus and respect for elders and wisdom keepers. The St. Croix River valley was a thriving cultural landscape, home to numerous villages and seasonal encampments.

European Arrival and Early Encounters: The arrival of Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries marked a dramatic turning point. French explorers like Samuel de Champlain made contact with the Passamaquoddy in the early 1600s, establishing early relationships, often built on trade. The French, seeking furs and alliances, generally pursued a different colonization strategy than the English, often integrating more with native communities. This era saw the introduction of European goods, but also devastating diseases like smallpox, which decimated indigenous populations who had no natural immunity.

Colonial Conflicts and Land Encroachment: As English and later American colonial power grew, the Passamaquoddy found themselves caught in geopolitical struggles between competing empires. The Revolutionary War, in particular, saw the Passamaquoddy align with the American cause, contributing significantly to the war effort in hopes of securing their land rights and sovereignty. Despite their contributions, their traditional lands were increasingly encroached upon by American settlers, loggers, and fishermen. Unlike many other tribes, the Passamaquoddy never signed a comprehensive treaty with the United States relinquishing their aboriginal title to their lands. This critical detail would become the cornerstone of their future legal battles.

The Era of Dispossession and Marginalization: The 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of intense hardship. The Passamaquoddy were largely confined to small, often inadequate reservations, their traditional ways of life disrupted, and their access to ancestral hunting and fishing grounds severely restricted. State governments, rather than the federal government, often managed their affairs, leading to further neglect and exploitation. Policies of assimilation sought to erase their language and culture, forcing children into boarding schools and suppressing traditional practices. Yet, through it all, the Passamaquoddy maintained their identity, their language, and their oral traditions, passing them down through generations as acts of resistance and cultural preservation.

The Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980: A Landmark Victory: The tide began to turn in the mid-20th century with the burgeoning Native American rights movement. The Passamaquoddy, along with the Penobscot Nation, launched a groundbreaking legal challenge, asserting their aboriginal title to vast tracts of land in Maine under the Indian Nonintercourse Act of 1790, which required Congressional approval for any land transactions with Native American tribes. Since no such approval had ever been granted for the state’s acquisition of Passamaquoddy lands, the tribes argued that their original title remained intact.

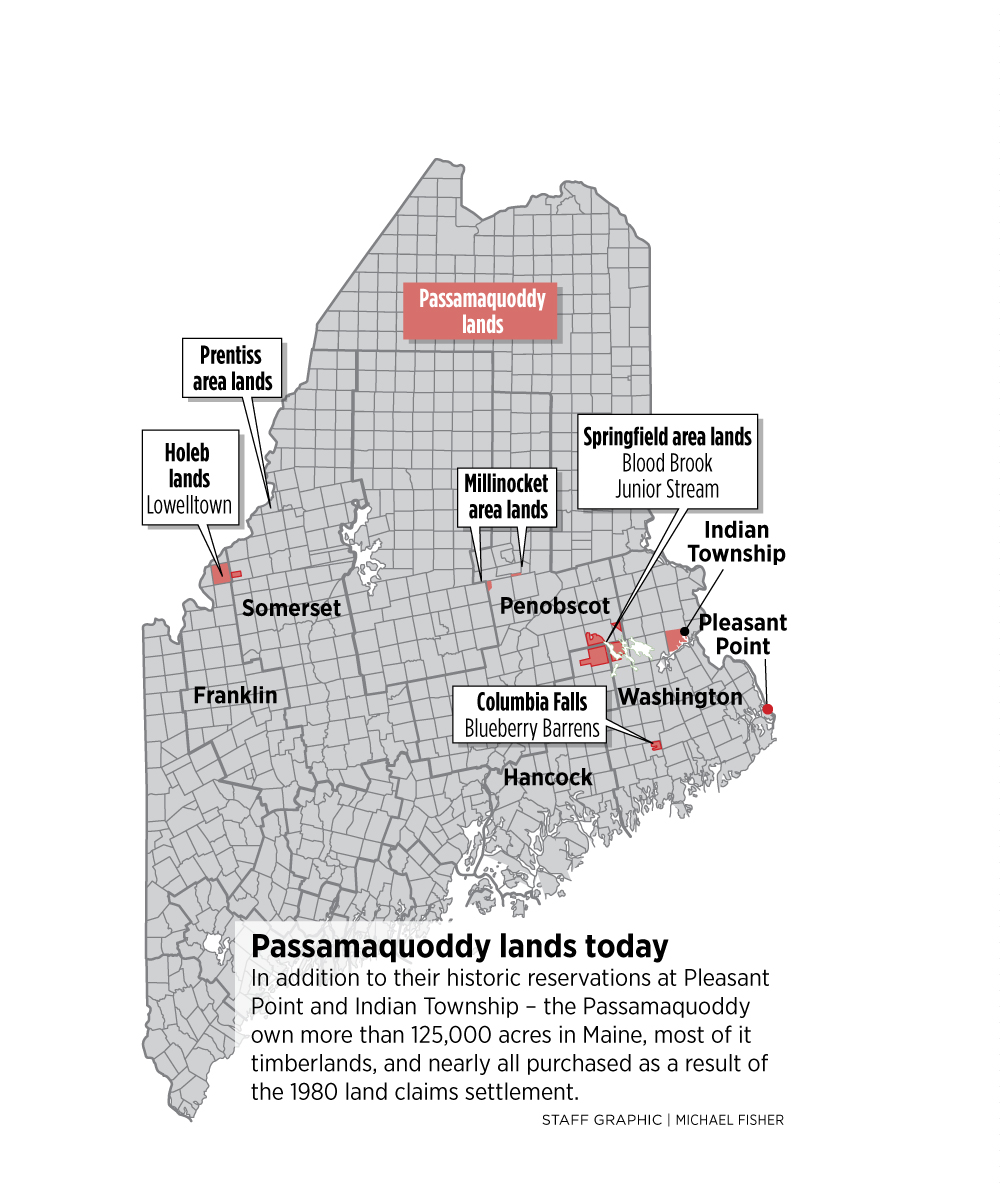

This legal battle culminated in the landmark Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act of 1980. While not returning all of their ancestral lands, the settlement was a monumental achievement. It affirmed the tribes’ sovereignty, provided them with federal recognition, and compensated them with $81.5 million (shared with the Penobscot Nation) to acquire over 300,000 acres of land and establish a perpetual trust fund. This Act was not just about money and land; it was a profound recognition of their inherent rights, their unbroken chain of history, and their status as sovereign nations within the state of Maine.

Identity Forged in the Landscape

For the Passamaquoddy, their traditional lands are not merely a resource base or a historical backdrop; they are intrinsic to their identity. The language itself, Peskotomuhkatiyil, is deeply intertwined with the landscape. Place names tell stories, describe geographical features, and convey historical events, connecting generations to the land in a way that goes far beyond simple nomenclature. To lose the land would be to lose a fundamental part of who they are.

Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), passed down orally for millennia, reflects an intimate understanding of the cycles of the seasons, the behavior of animals, the properties of plants, and the health of the waterways. This knowledge, now increasingly recognized by Western science, is vital for environmental stewardship and sustainable resource management, areas in which the Passamaquoddy continue to lead. Their ceremonies, spiritual practices, and social structures are all rooted in their relationship with the natural world, reinforcing a deep sense of responsibility to protect and preserve the land for future generations.

The Modern Passamaquoddy: Sovereignty and Stewardship

Today, the Passamaquoddy Tribe at Motahkomikuk and Sipayik are self-governing nations, actively working to revitalize their culture, language, and economic well-being. They own and manage forests, engage in sustainable aquaculture, operate businesses, and provide essential services to their communities. Their commitment to environmental protection, particularly concerning the health of the St. Croix River and Passamaquoddy Bay, is a testament to their enduring role as stewards of the land.

However, challenges remain. Issues of sovereignty, environmental justice, and economic equity continue to be pressing concerns. The fight to protect sacred sites, restore traditional fishing rights, and ensure the health of their traditional waters is ongoing. Yet, the Passamaquoddy continue to thrive, demonstrating remarkable strength and adaptability, rooted in their ancestral connection to the Dawnland.

For the Traveler and Learner: A Call to Deeper Understanding

For those who travel to Maine, understanding the Passamaquoddy traditional lands map offers an invaluable lens through which to experience the state. It transforms a scenic landscape into a vibrant cultural tapestry, rich with history and meaning.

- Acknowledge and Learn: Before visiting any part of Maine, take the time to learn about the indigenous peoples whose ancestral lands you are on. Websites of the Passamaquoddy Tribe, the Wabanaki Confederacy, and educational institutions offer a wealth of information.

- Respect the Land: Understand that many natural areas you visit, from Acadia National Park to inland lakes, were once vital parts of Passamaquoddy territory. Practice responsible tourism, leave no trace, and respect the natural environment.

- Support Tribal Initiatives: Where possible, seek out and support tribal-owned businesses, cultural centers, and museums. These offer authentic perspectives and directly contribute to tribal communities. The Waponahki Museum and Cultural Center at Sipayik, for example, is an excellent resource for learning about Passamaquoddy history and culture.

- Listen to Indigenous Voices: The best way to learn about the Passamaquoddy is to listen to their own voices, stories, and perspectives. Seek out opportunities to engage with tribal members respectfully, if available, or through their official publications and media.

The Passamaquoddy traditional lands map of Maine is more than a historical artifact; it is a dynamic representation of a people’s enduring spirit, their profound connection to their ancestral territory, and their ongoing journey of self-determination. By embracing this deeper narrative, travelers and learners can gain a richer, more meaningful appreciation for the breathtaking beauty and complex history of the Dawnland, honoring the original inhabitants who have shaped and sustained it for millennia. Their story is not just a part of Maine’s past; it is a vital, living part of its present and its future.