Navigating the Invisible Maps: Canyon de Chelly and the Living Legacy of Native American Boundaries

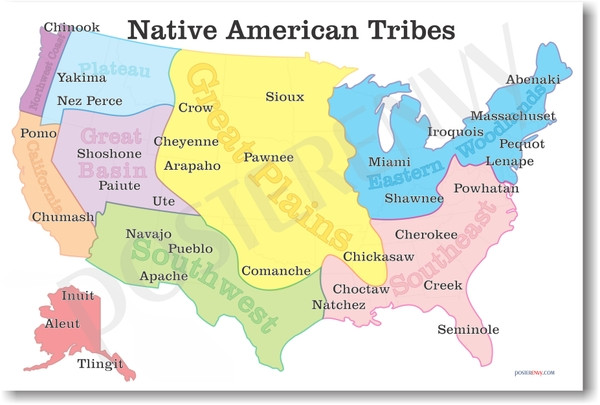

Forget the neat, color-coded lines on historical maps. To truly grasp the complex, fluid, and often heartbreaking reality of Native American tribal boundaries, one must step into the landscape itself, where the earth remembers, and the wind whispers stories of millennia. There are few places in North America that offer such a profound, visceral journey into this historical cartography as Canyon de Chelly National Monument in northeastern Arizona. This isn’t just a place to observe ancient ruins; it’s a living classroom for understanding the dynamic interplay of land, culture, conflict, and the enduring spirit of sovereignty that defines Native American territories.

Canyon de Chelly, pronounced "de-SHAY," is not just a national monument; it is entirely within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation (Diné Bikéyah) and co-managed by the National Park Service and the Navajo Nation. This unique arrangement immediately underscores its significance as a contemporary tribal territory, but its deep, red sandstone walls, carved by millions of years of water and wind, hold layers of history that predate even the Navajo. A journey here is a descent not just into a canyon, but into a multi-tribal historical narrative, where boundaries were once defined by survival, trade, and spiritual connection, long before they were etched onto paper by colonial powers.

The Canyon as a Palimpsest of Peoples

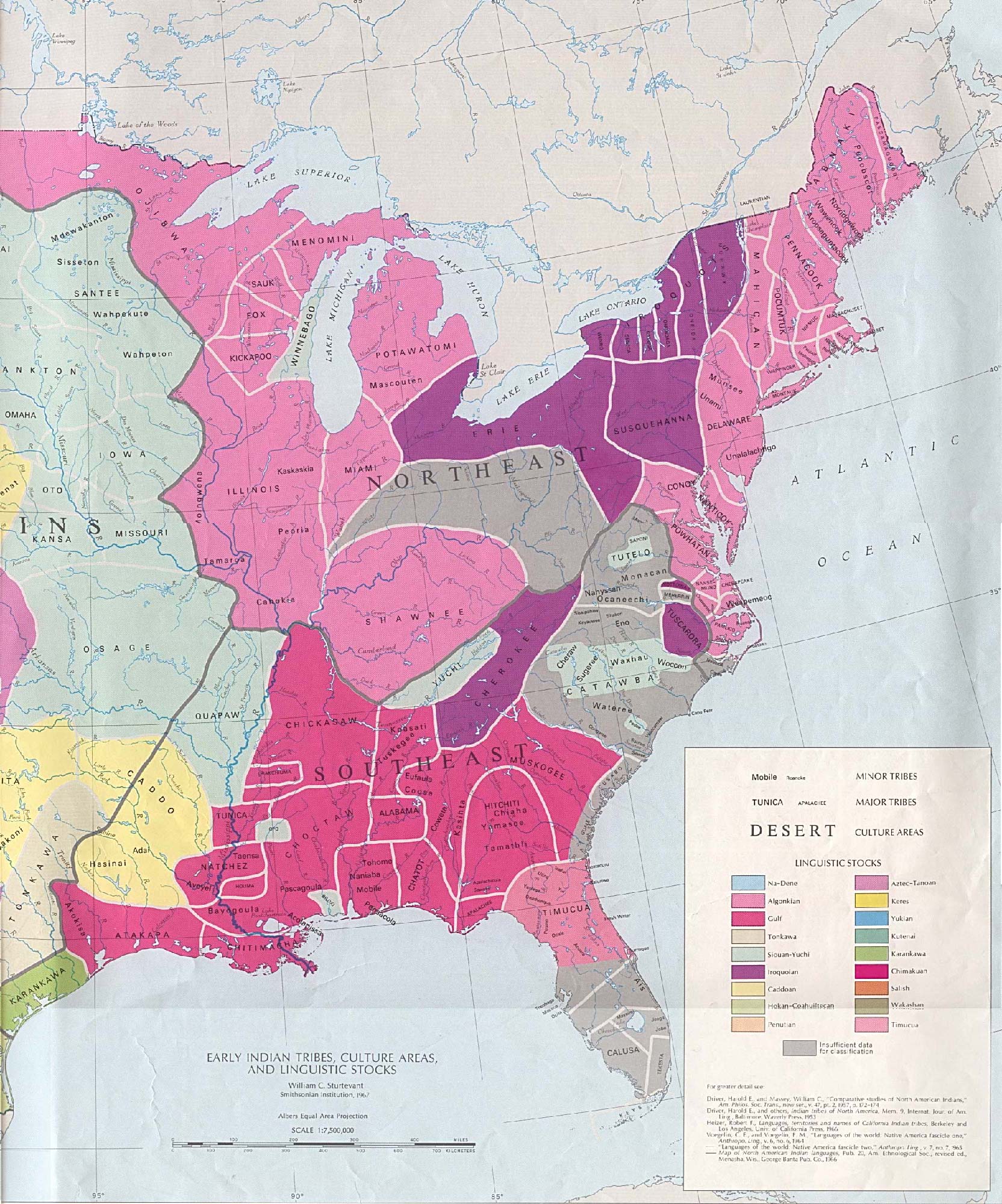

To understand tribal boundaries here, one must first recognize the succession of peoples who have called this place home. The earliest known inhabitants, the Ancestral Puebloans (often referred to as Anasazi, a Navajo word meaning "ancient enemies," though modern scholarship prefers Ancestral Puebloans), established thriving communities within the canyon’s alcoves and on its mesas as early as 2500 BCE. Their cliff dwellings, like the iconic White House Ruin, stand as silent testament to a sophisticated agricultural society that cultivated maize, beans, and squash, and developed intricate social structures. Their "boundaries" were not lines on a map but zones of influence, trade networks extending across the Southwest, and areas where their distinctive pottery styles and architectural forms predominated. They interacted with, and sometimes conflicted with, other groups like the Mogollon and Hohokam, their territorial distinctions more about cultural spheres and resource access than rigidly drawn borders.

By the 14th century, the Ancestral Puebloans had largely departed the canyon, migrating south and east to become the ancestors of today’s Pueblo peoples, including the Hopi, Zuni, and Acoma. Many Hopi traditions still recount their ancestors’ passage through places like Canyon de Chelly, laying claim to a spiritual and historical connection to this land, a connection that sometimes intersects with current Navajo perspectives. This historical overlap highlights how ancestral lands often transcend current reservation lines, creating complex layers of belonging and heritage.

Then came the Diné, the Navajo people, migrating south from present-day Canada around the 15th century. They adopted agriculture, learned weaving techniques, and established a profound spiritual and practical relationship with the canyon. For the Navajo, Canyon de Chelly became a sanctuary, a fertile haven for their sheep, cornfields, and families. Its high walls offered natural defense, and its hidden passages provided refuge. This was their homeland, their dinetah, a territory defined not by external decree but by their presence, their traditions, and their deep spiritual ties to the landscape. Spider Rock, a towering sandstone spire, for instance, is not merely a geological formation but the sacred home of Spider Woman, a crucial figure in Navajo cosmology. Such features are intrinsic markers of their spiritual and cultural boundaries, defining the heart of their world.

The Imposition of Lines: Conflict and Resilience

The true impact of "historical Native American tribal boundaries maps" becomes starkly clear when considering the arrival of European and later American colonizers. The fluid, culturally-defined territories of the Diné, like those of countless other tribes, were suddenly confronted with a foreign concept: fixed, surveyed, and legally enforced borders. The 19th century brought increasing pressure, culminating in the tragic "Long Walk" of 1864, when Kit Carson, under orders from the U.S. government, systematically destroyed Navajo crops and livestock in Canyon de Chelly, forcing thousands into a brutal march to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico.

Canyon de Chelly, for a time, ceased to be a secure Navajo stronghold. Yet, even during this forced removal, the Navajo people clung to their identity and their claim to their ancestral lands. Upon their return in 1868, they re-established their presence, and the subsequent establishment of the Navajo Reservation, though significantly smaller than their traditional dinetah, encompassed Canyon de Chelly. This historical event vividly illustrates the violent imposition of new boundaries over existing, organic ones, and the resilience required to reclaim and hold onto a homeland. The modern Navajo Nation boundary, the largest reservation in the U.S., is a testament to that enduring struggle and a living example of a tribal territory that continues to evolve.

Experiencing the Boundaries: A Traveler’s Perspective

For the contemporary traveler, Canyon de Chelly offers a unique opportunity to engage with these complex layers of history and boundaries. From the rim, accessible via scenic overlooks, one can gaze down into the verdant canyon floor, observing both the ancient cliff dwellings and the active Navajo farms below – a visual juxtaposition of past and present. But to truly understand, one must descend.

Access to the canyon floor is restricted, requiring a certified Navajo guide, and this restriction itself is a powerful statement about tribal sovereignty and the living nature of these boundaries. A guided tour is not just an archaeological excursion; it’s an immersion into contemporary Navajo culture and a direct encounter with a living tribal boundary. As your guide, a member of the Navajo Nation, navigates the sandy washes and points out petroglyphs, ancient ruins, and modern hogans (traditional Navajo homes), they don’t just share facts; they share stories, traditions, and a deep, personal connection to this land.

They might explain how certain plants are used in traditional medicine, or recount the history of their own family’s presence in the canyon for generations. They might speak of the sacredness of the cottonwood trees, or the meaning of the pictographs left by their ancestors. This direct engagement allows you to understand that for the Navajo, the canyon is not merely a historical site but a spiritual homeland, a vibrant community, and an active part of their cultural identity. The boundaries of their nation are not just lines on a map; they are the paths they walk, the stories they tell, and the stewardship they practice.

Visiting the White House Ruin with a Navajo guide, for example, transforms it from a mere archaeological curiosity into a place of deep cultural significance. The guide might explain how the Ancestral Puebloans built their homes, but also how their own Navajo ancestors interacted with and learned from these earlier inhabitants. They might even share a Navajo perspective on why the Ancestral Puebloans eventually left, weaving together geological, environmental, and spiritual narratives that challenge Western historical interpretations. This experience highlights how different tribes hold different narratives and claims to the same physical spaces, further complicating any simplistic notion of a single "historical map."

Beyond the Lines: A Deeper Understanding

Canyon de Chelly is a profound reminder that "historical Native American tribal boundaries maps" are vastly insufficient tools for understanding the true tapestry of indigenous land tenure. These maps often flatten complex, multi-layered realities into static lines, failing to capture:

- Fluidity and Overlap: Traditional boundaries were often dynamic, shifting with seasons, resource availability, and inter-tribal relations. They were zones of influence, not rigid borders.

- Cultural and Spiritual Significance: Boundaries were not just about land ownership but about spiritual connection, sacred sites, and cultural identity. The land is the culture.

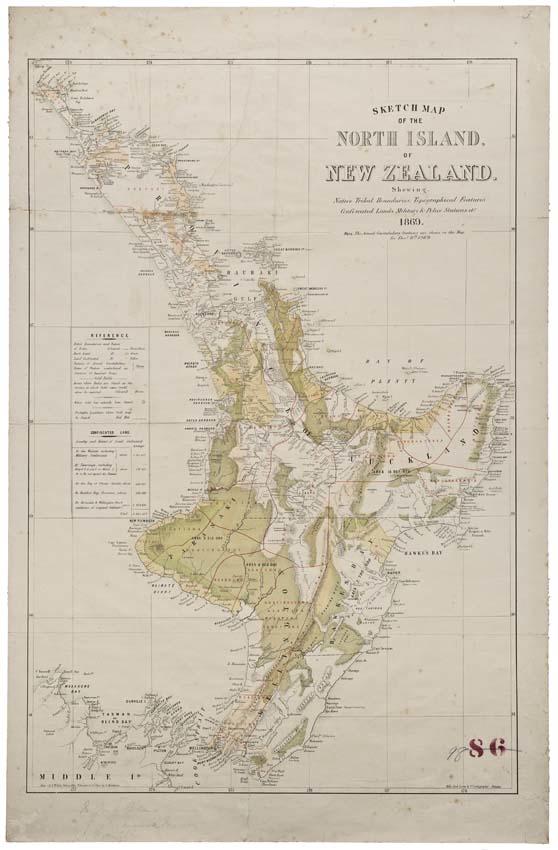

- Colonial Imposition: Many existing reservation boundaries are the direct result of treaties, forced removals, and political negotiations, often bearing little resemblance to traditional territories.

- Ongoing Sovereignty: Modern tribal nations continue to assert their sovereignty and stewardship over their lands, navigating the complexities of historical claims, contemporary needs, and federal oversight.

In Canyon de Chelly, you don’t just see the remnants of ancient cultures; you witness the continuous, unbroken presence of the Navajo people. You feel the weight of history, the scars of conflict, and the enduring strength of cultural identity tied inextricably to the land. It forces you to rethink what a "map" truly represents. Is it just a drawing, or is it the very ground beneath your feet, imbued with generations of stories, struggles, and triumphs?

This journey into Canyon de Chelly is more than a scenic adventure; it’s an essential pilgrimage for anyone seeking to understand the true depth and complexity of Native American history and the living legacy of their territorial claims. It teaches us that to truly see the map, we must look beyond the lines and listen to the land itself, guided by those who have called it home for millennia. In doing so, we not only honor the past but also gain a deeper appreciation for the ongoing struggles and triumphs of indigenous nations today.