Navigating the Ancestral Tapestry: A Traveler’s Guide to Native American Maps and Lands in the American Southwest

Maps are more than mere lines on paper; they are narratives, repositories of history, culture, and identity. For the conscious traveler seeking to understand the deep, resonant history of the American continent, there is no more profound journey than exploring the ancestral lands and enduring cultures of Native American tribes. This isn’t just about visiting a site; it’s about engaging with the cartography of indigenous presence, past and present, a story often overshadowed by colonial narratives. My recent immersion into the American Southwest provided an unparalleled opportunity to witness this firsthand, revealing how Native American tribes maps are not static historical documents but living, breathing testaments to sovereignty, heritage, and resilience.

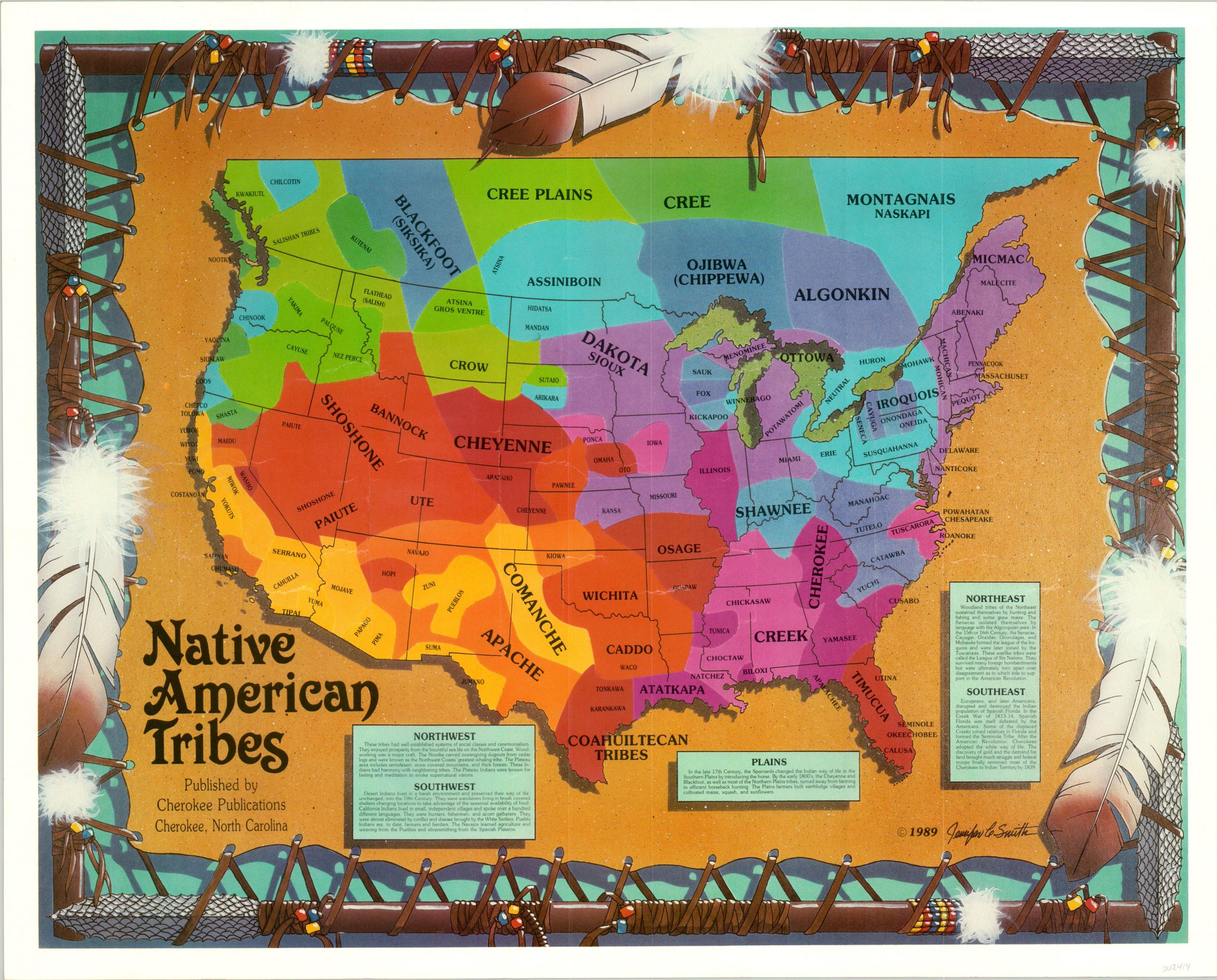

My journey began with a singular purpose: to move beyond the simplistic "Indian reservations map" often found in textbooks and delve into the intricate layers of indigenous cartography, from pre-contact migration routes to contemporary land claims. The American Southwest, with its staggering concentration of diverse tribal nations, ancient pueblos, and vast traditional territories, emerged as the ideal starting point. This region, encompassing parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, offers a unique window into the rich tapestry of Indigenous North America.

The Heard Museum: A Gateway to Understanding Indigenous Cartography

My first critical stop, and arguably the most vital for setting the stage, was the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. Far more than a traditional art museum, the Heard serves as a premier institution dedicated to the advancement of Native American art and cultures. Stepping inside, one immediately senses the reverence and scholarship that permeate its halls. It’s here that the concept of "Native American tribes maps" begins to unfold in its truest, most complex form.

The Heard’s extensive exhibits, meticulously curated, immediately challenge preconceived notions of a singular "Native American" identity. Instead, you encounter a vibrant mosaic of distinct nations: the Navajo (Diné), Hopi, Apache, Zuni, Maricopa, Pima (Akimel O’odham), Pueblo peoples, and countless others. The exhibits often incorporate visual representations of their historical and current territories. These aren’t just static displays; they are dynamic illustrations of indigenous land tenure and traditional land use.

I spent hours studying the detailed maps illustrating historical Native American migration routes across the Southwest, revealing ancient trade networks and seasonal hunting grounds long before European contact. Interactive exhibits allowed me to zoom in on ancestral lands maps, distinguishing between treaty lands maps and current reservation boundaries. This distinction is crucial, as many tribal nations’ historical land claims vastly predate and often exceed their present-day reservation borders. The museum does an excellent job of highlighting the discrepancies, using historical Native American territory maps to contextualize modern land disputes and ongoing efforts for Native American land restoration.

Furthermore, the Heard provides fascinating insights into linguistic maps of Native American tribes, showcasing the incredible diversity of language families within the region, such as Athabaskan (Navajo, Apache), Uto-Aztecan (Hopi), and Kiowa-Tanoan (some Pueblo languages). These indigenous language maps are vital, as language is intrinsically linked to cultural identity and often defines the extent of a tribe’s traditional territory and worldview. The museum’s collection of Native American art maps—works that integrate geographical elements into artistic expression—also underscores the deep connection between people, place, and creative expression.

The Heard Museum’s comprehensive approach to mapping extends to contemporary issues, showcasing modern Native American land maps that address water rights, resource management, and economic development within sovereign nations. It’s a powerful reminder that maps are not just about the past; they are critical tools for the future of indigenous self-determination.

Beyond the Museum: Experiencing Sovereign Nations and Sacred Landscapes

Armed with a deeper understanding from the Heard, my journey continued into the landscapes themselves, traversing vast stretches of what are today recognized as Native American reservations map areas. Driving through the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the United States, is a profound experience. Here, maps take on a different dimension – they are not just informational, but deeply spiritual.

Navajo Nation, or Diné Bikeyah, is a sovereign nation with its own government, laws, and cultural protocols. Understanding this requires consulting specific tribal maps and reservation maps provided by the Navajo Nation itself, rather than relying solely on general state maps. These official tribal maps delineate not only administrative boundaries but also highlight sacred sites, historical trails, and community centers. Visiting places like Canyon de Chelly National Monument, which is jointly managed by the National Park Service and the Navajo Nation, truly brought the concept of ancestral homeland maps to life. The canyon walls whisper stories of the Diné people’s long history, visible in ancient cliff dwellings and petroglyphs—physical markers on the landscape that serve as their own form of map, chronicling centuries of habitation.

Further south, the Hopi Mesas represent a different, yet equally powerful, indigenous cartography. The Hopi villages, perched atop remote mesas, are among the oldest continuously inhabited settlements in North America. Here, the Hopi tribal maps are not just geographical; they are cosmological. Their worldview, deeply tied to the land, dictates everything from agricultural practices to ceremonial cycles. Understanding Hopi territory requires appreciating their intricate system of dry farming and their deep spiritual connection to specific geological formations and natural resources. This is where cultural maps of Native American tribes become paramount, illustrating how sacred sites, pilgrimage routes, and resource areas are interwoven into the fabric of their identity.

The Zuni Pueblo, another ancient community in New Mexico, offers similar insights. Their Zuni reservation map reflects a unique history and spiritual connection to their sacred mountain, Dowa Yalanne (Corn Mountain). Engaging with these communities means moving beyond tourist routes and seeking out tribal cultural centers and authorized guides who can share the stories embedded in the landscape. This is where educational Native American maps come into play, often provided by the tribes themselves, offering insights into their specific histories, governance, and cultural practices.

The Intricacy of Indigenous Cartography: Beyond Western Conventions

One of the most enlightening aspects of this journey was the realization that indigenous cartography often transcends the conventional Western concept of a map. For many Native American tribes, maps weren’t always drawn on paper with cardinal directions. They were embedded in oral traditions, passed down through generations of storytelling. They were etched into the landscape itself through sacred geography maps, marked by rock formations, star alignments, and seasonal cycles.

Consider the pre-colonial indigenous maps – these were often mental maps, reinforced by song, dance, and ceremony, detailing hunting grounds, water sources, migration paths, and sacred sites with incredible accuracy. Native American star maps guided journeys and agricultural practices. Traditional ecological knowledge maps conveyed intricate understanding of plant and animal habitats, essential for survival and sustainable living.

Modern technology, however, has provided new avenues for indigenous communities to represent and assert their territorial claims. Many tribes are now utilizing GIS Native American maps (Geographic Information Systems) to document their ancestral lands, track environmental changes, and manage their resources. These digital Native American maps are powerful tools for Native American land rights advocacy, allowing tribes to visually demonstrate their historical connection to the land in contemporary legal and political contexts. Projects like interactive Native American maps online are emerging, often developed by tribes or in collaboration with universities, making this rich cartographic heritage accessible to a global audience. These platforms often feature historical Native American population maps, treaty boundaries maps, and Native American cultural heritage maps, providing layers of information that challenge colonial land narratives.

Maps as Tools for Advocacy, Preservation, and Future Resilience

The maps I encountered, whether in museum exhibits or in the very landscapes of the Southwest, are not merely historical curiosities. They are vibrant tools for advocacy, cultural preservation, and future resilience.

Native American land claim maps are at the forefront of ongoing legal battles, asserting tribal sovereignty and demanding the return or recognition of lands unlawfully taken. Native American water rights maps are crucial in the arid Southwest, where access to water is a matter of life and death, reflecting complex legal histories and environmental challenges. Environmental protection maps for Native American lands highlight areas of cultural significance and ecological sensitivity that tribes are working tirelessly to protect from industrial development or climate change impacts.

The journey underscored how maps of Native American historical sites are not just about ancient ruins but about the living presence of peoples who continue to inhabit, steward, and draw identity from these places. This includes Native American spiritual sites maps, which delineate areas of profound cultural and religious significance, often requiring respectful access protocols and protection from desecration.

For travelers, engaging with these maps and the places they represent is a profound educational experience. It’s an opportunity to learn about Native American self-governance, the complexities of tribal land management, and the ongoing efforts of Native American cultural revitalization. It encourages supporting Native American tourism initiatives that directly benefit tribal communities, ensuring that economic development aligns with cultural values.

A Conscious Traveler’s Compass: Respect and Engagement

My review of this "place" – the American Southwest as a living map of Native American heritage – would be incomplete without emphasizing the ethical responsibilities of the traveler. To truly appreciate the depth of Native American map resources and the cultures they represent, one must approach with respect, humility, and a willingness to learn.

This means:

- Consulting Tribal Websites: Many tribes provide official tribal websites with maps and visitor information, detailing cultural protocols, permit requirements, and recommended experiences. These are invaluable for planning a respectful visit.

- Supporting Local Economies: Prioritize Native American-owned businesses, artists, and guides. Their insights are invaluable, and your support directly benefits the communities.

- Respecting Sacred Sites: Understand that many places are deeply spiritual. Always seek permission, follow guidelines, and never disturb artifacts or natural features.

- Learning the History: Engage with resources like the Heard Museum, Native American atlases, and academic works. Seek out Native American history maps that offer indigenous perspectives rather than colonial interpretations.

- Understanding Sovereignty: Recognize that reservations are sovereign nations. Respect their laws, customs, and leadership.

My journey through the American Southwest, guided by the intricate and powerful narratives of Native American maps, was transformative. It moved me beyond abstract geographical concepts to a profound appreciation for the enduring presence, rich history, and vibrant future of Indigenous North America. These maps are not just guides to locations; they are invitations to understanding, empathy, and respectful engagement with a heritage that continues to shape the very soul of the continent. For any traveler seeking a truly meaningful and educational experience, charting a course through the ancestral tapestry of Native American lands is an imperative, offering insights that will resonate long after the journey concludes.