Navigating the Ancestral Current: Experiencing the Columbia River Basin Through Indigenous Maps

To travel the Columbia River Basin today is to traverse a landscape of immense power and beauty – a mosaic of soaring mountains, fertile plateaus, and the mighty Columbia River, carving its path to the Pacific. But to truly experience this land, to feel the pulse of its ancient heart, you must look beyond modern road maps and GPS coordinates. You must delve into the cartography of its first inhabitants, the Native American peoples whose sophisticated understanding of this vast territory shaped millennia of navigation, trade, and cultural life. This isn’t a review of a static museum exhibit; it’s an invitation to experience the Columbia River Basin itself, through the profound and illuminating lens of indigenous maps.

Imagine a map that isn’t drawn on paper but etched into memory, woven into stories, carved into stone, or painted on hides. These were the original navigational tools of the Columbia River Basin, predating European contact by thousands of years. Far from crude, these maps were rich, multi-dimensional guides, reflecting not just geography but ecology, history, and spiritual connection. They were living documents, constantly updated through oral tradition, guiding hunters to game, traders along intricate networks, and entire communities to seasonal food sources. To understand these maps is to unlock a deeper layer of the Columbia, transforming a scenic drive or a challenging hike into a journey through time, guided by ancestral wisdom.

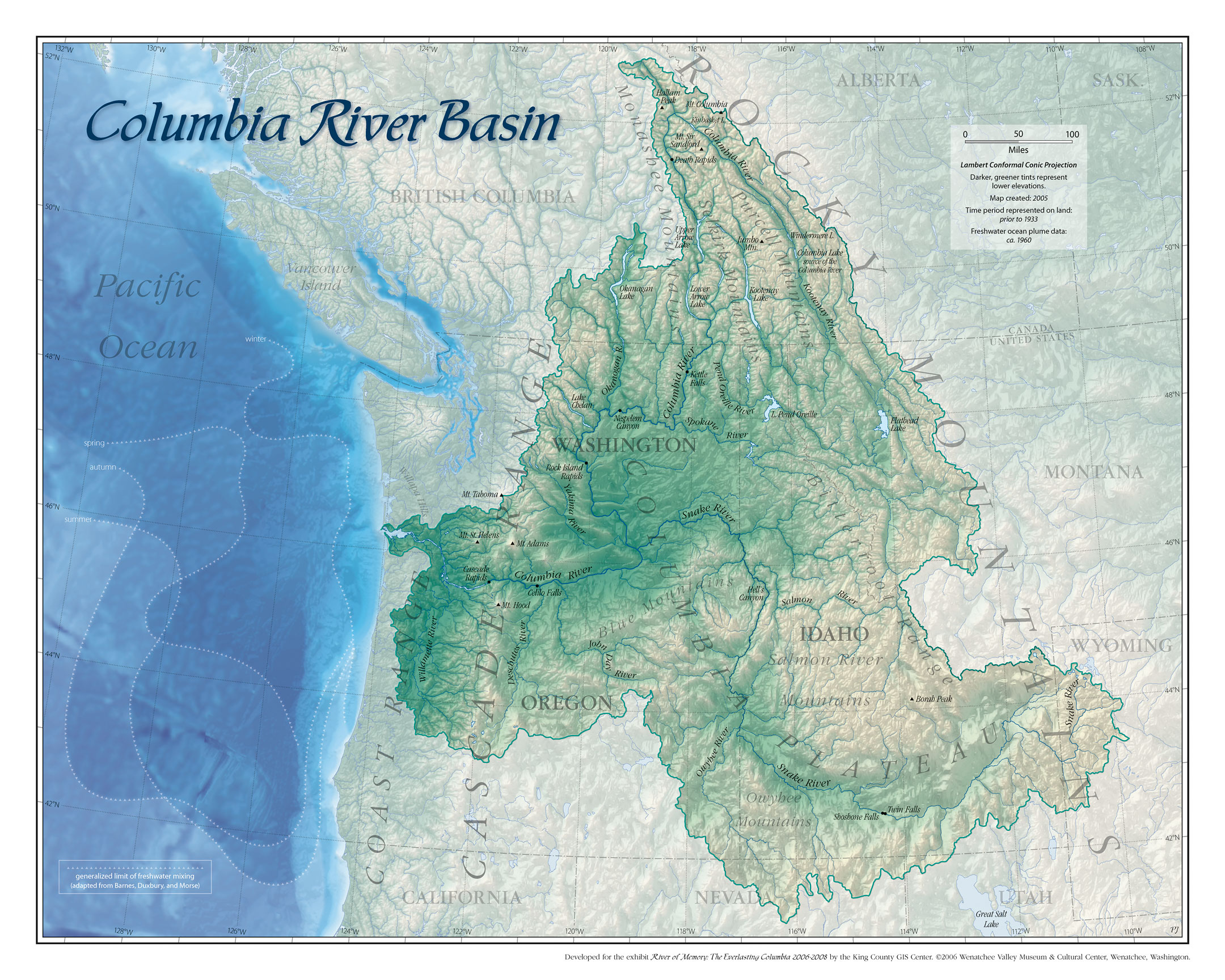

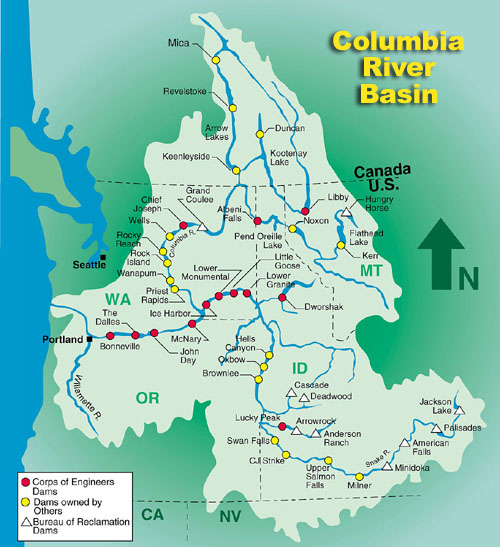

The Columbia River itself, the Nch’i-Wána ("the great river") to many indigenous peoples, is the undisputed protagonist of these ancestral maps. For thousands of years, it was the superhighway of the Pacific Northwest, a dynamic artery connecting disparate communities. Indigenous maps emphasize the river’s key features: the location of abundant salmon runs, the treacherous rapids requiring portages, the strategic fishing platforms, and the confluence points of major tributaries like the Snake, Yakima, and Willamette.

Consider Celilo Falls, once the economic and cultural heart of the entire basin, now submerged beneath the waters of The Dalles Dam. Ancestral maps wouldn’t just mark its location; they would depict the specific fishing grounds, the trails for portaging canoes and goods, and the seasonal gathering places where tribes from across the region converged for trade and ceremony. Today, while the falls are gone, standing at a viewpoint overlooking the tranquil reservoir, knowing that beneath you lies one of the most significant cultural sites in North American history, brings a profound sense of loss and respect. The ancestral map, even if only a mental one, allows you to "see" the falls, to hear the roar of the water and the bustle of thousands of people, making the landscape resonate with its vibrant past.

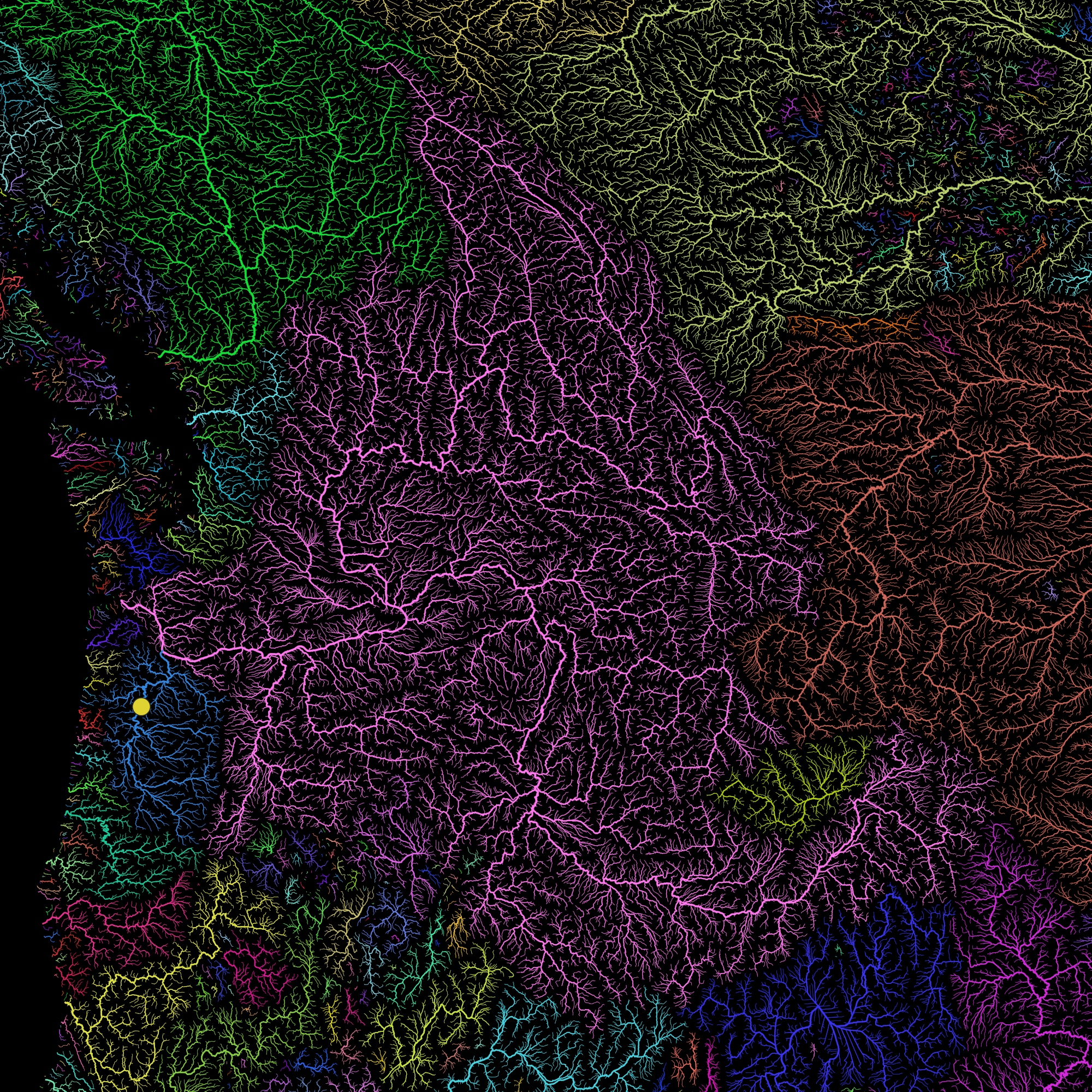

Beyond the main stem of the Columbia, indigenous maps intricately detailed the web of tributary rivers and overland trails. The Yakima River, for instance, would be mapped with precision, showing the best places to spear fish, where to find camas root prairies, and the paths leading into the surrounding mountains for hunting deer and elk. The Snake River, stretching deep into Idaho, was another crucial artery, its course marked by prominent landforms, hot springs, and vital resource areas. For a traveler exploring the Columbia Gorge or the plateaus of Eastern Washington and Oregon, these insights are invaluable. Hiking a modern trail, you might unwittingly be following an ancient trade route, a path trodden by countless generations. Understanding this historical context transforms a simple hike into a walk through living history, each turn in the trail echoing with footsteps of the past.

These maps weren’t simply lines on a surface; they were imbued with ecological knowledge. They highlighted the seasonal availability of resources: where and when to find huckleberries in the mountains, the optimal times for salmon fishing in specific tributaries, or the locations of traditional hunting grounds. They showcased a deep, reciprocal relationship with the land, a nuanced understanding of its rhythms and bounty. For the modern traveler, this perspective encourages a more mindful engagement with the environment. When you visit a designated berry-picking area or observe wildlife in a national park within the basin, these ancestral maps prompt you to consider the millennia of sustainable resource management and ecological wisdom that shaped the landscape you see today.

Crucially, indigenous maps transcended mere practicality, incorporating spiritual and cultural dimensions. They marked sacred sites, places of creation stories, areas associated with mythical beings, and locations of ancestral significance. Rock art sites, like those found along the Columbia Hills State Park in Washington or pictograph panels elsewhere in the basin, serve as powerful visual records, acting as a form of enduring cartography that blends narrative with geography. These aren’t just pretty pictures; they are visual representations of spiritual journeys, historical events, and a deep connection to the land. Visiting these sites, with an awareness of their profound significance to the original inhabitants, transforms them from archaeological curiosities into powerful spiritual landscapes, inviting quiet contemplation and deep respect.

So, how does one "review" or "experience" these indigenous maps today? It’s a multi-faceted journey that enriches any travel through the Columbia River Basin.

First, seek out the direct descendants of these cartographers. Tribal museums and cultural centers throughout the basin are invaluable resources. The Tamástslikt Cultural Institute near Pendleton, Oregon, for instance, offers compelling exhibits that directly interpret the history, culture, and land connections of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, often featuring reproductions or interpretations of ancestral maps and trade routes. The High Desert Museum in Bend, Oregon, also provides excellent insights into the indigenous history of the region. Many smaller tribal museums and interpretive centers offer even more localized and personal perspectives, often displaying artifacts and oral histories that illuminate specific parts of the basin. These institutions provide the essential narratives and interpretations that bring the maps to life, translating abstract concepts into tangible understanding.

Second, engage with the landscape through an informed lens. Before you visit a specific area within the basin – be it a state park, a scenic overlook, or a stretch of river – research the indigenous peoples who traditionally inhabited that land. Websites of tribal nations, local historical societies, and academic resources can provide invaluable context. Understanding the traditional names of mountains, rivers, and features, and learning about the activities that once took place there, allows you to superimpose the ancestral map onto your modern experience. When you stand on the banks of the Columbia, imagine the dip-net fishermen at Celilo, the vast trading networks, and the canoes laden with salmon and goods. When you hike a trail, visualize it as part of a millennia-old network connecting communities and resources.

Third, look for the physical remnants of these maps. Petroglyph and pictograph sites are perhaps the most direct visual evidence of indigenous cartography and storytelling. While some are in remote locations, many are accessible in state parks or protected areas, often with interpretive signage. These ancient rock art panels are not just beautiful; they often depict animals, human figures, and symbols that communicate stories, territorial claims, and navigational information. Approaching these sites with respect and a willingness to learn their deeper meanings unlocks a direct connection to the original mapmakers.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, travel with an open mind and a spirit of respect. The Columbia River Basin is ancestral land, and its history is deeply intertwined with the stories and wisdom of its indigenous peoples. By consciously seeking out their perspectives and understanding their cartographic traditions, you are not just gaining historical knowledge; you are participating in an act of recognition and honoring. You are learning to see the land not merely as a collection of physical features, but as a living entity, imbued with meaning, memory, and an unbroken chain of human connection.

In conclusion, "reviewing" the Columbia River Basin through the lens of Native American maps is not about finding a single location; it’s about a profound shift in perspective that transforms the entire region into an open-air museum and a living history lesson. It’s a journey from passive observation to active engagement, where every bend in the river, every mountain peak, and every ancient trail tells a story rooted in millennia of indigenous stewardship and knowledge. This approach to travel offers an unparalleled depth of understanding, allowing you to navigate not just the physical landscape, but also the rich cultural and spiritual currents that continue to flow through the heart of the Pacific Northwest. It’s an invitation to travel deeper, to see more, and to truly connect with the ancestral spirit of the Columbia.