The Ohio Valley, a verdant expanse carved by the mighty river and its tributaries, is more than just a geographical region; it is a profound historical archive, a landscape etched with the stories and spatial knowledge of countless Indigenous generations. For the discerning traveler seeking to understand the deep history of North America, engaging with the Native American maps of the Ohio Valley offers an unparalleled journey – not just across physical space, but through time, culture, and an entirely different way of seeing the world. This isn’t a review of a single museum exhibit, but an invitation to explore the very ground beneath your feet as a living, breathing cartographic masterpiece.

Forget the conventional paper maps you’re used to. Indigenous cartography, particularly in a dynamic and resource-rich region like the Ohio Valley, transcends mere lines and symbols on a static surface. Here, "maps" manifest as oral traditions passed down through generations, as mnemonic devices woven into intricate wampum belts, as petroglyphs carved into rock faces, and most strikingly, as monumental earthworks that literally sculpt the landscape into expressions of cosmology, territory, and trade routes. To truly experience the Ohio Valley through this indigenous lens is to understand that the land itself is the map.

The Ohio Valley, encompassing parts of modern-day Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, served for millennia as a vital crossroads. It was a place of immense fertility, supporting diverse cultures like the Adena, Hopewell, and Fort Ancient peoples, who thrived here for thousands of years before European contact. Their societies were complex, interconnected by vast trade networks that stretched across the continent, necessitating sophisticated spatial awareness and methods of conveying geographical information. Their maps were not just about getting from point A to point B; they were about understanding the spirit of the land, the cyclical movements of the stars, the location of sacred sites, and the boundaries of kinship and alliance.

Earthworks: The Grand-Scale Cartography of the Land

Perhaps the most compelling and enduring forms of Indigenous "maps" in the Ohio Valley are the monumental earthworks. These aren’t just ceremonial sites; they are profound expressions of spatial knowledge, aligning with celestial events, topographical features, and cardinal directions in ways that define territory, mark significant places, and even outline pathways for spiritual and communal journeys.

Consider the Newark Earthworks in Ohio, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and arguably the most spectacular surviving example of ancient geometric earthworks in the world. Built by the Hopewell culture between 100 BC and AD 500, this complex once spanned four square miles, featuring enormous circles, squares, and octagons. The Octagon Earthworks, for instance, is a perfect octagon encompassing 50 acres, precisely aligned to the moon’s major standstill cycle – an astronomical event that occurs only every 18.6 years. This alignment suggests an incredibly sophisticated understanding of celestial navigation and timekeeping, effectively using the landscape itself as a giant observatory and calendar. But beyond their astronomical function, these earthworks also defined a significant cultural and ceremonial hub, a central point within a wider Hopewell sphere of influence. They served as beacons, guiding travelers and defining the sacred geography of the region. Standing within the Great Circle or walking along the walls of the Octagon, one feels the immense scale and precision, understanding that this was a deliberate shaping of the land to reflect a cosmic and terrestrial order – a map of their universe.

Further south, Serpent Mound, another National Historic Landmark in Ohio, presents a different kind of cartographic marvel. This effigy mound, stretching over 1,348 feet across a plateau, depicts a massive, undulating serpent. While its exact purpose remains debated, many theories point to its function as a celestial calendar or a marker of significant astronomical events, particularly solstices and equinoxes. The serpent’s coils and head are aligned with various solar and lunar positions, effectively mapping the movements of celestial bodies onto the terrestrial plane. It’s a map not of routes, but of time and cosmic alignment, deeply connecting the people to the rhythms of the natural world. Viewing Serpent Mound from an elevated platform, its form unfolds, revealing the subtle curves and purposeful alignments that speak volumes about its builders’ knowledge of the land and sky.

The Fort Ancient Earthworks, also in Ohio, represent another layer of this landscape cartography. This sprawling enclosure, built by the Fort Ancient culture (AD 1000-1650), is one of the largest ancient hilltop enclosures in North America, covering 275 acres with three miles of earthen walls. While often described as defensive, its sheer size and numerous openings suggest a more complex purpose, perhaps functioning as a massive ceremonial center, a gathering place, or even a symbolic representation of tribal territories and ancestral domains. Its strategic location overlooking the Little Miami River valley suggests a deep understanding of the landscape for both practical (resource access) and symbolic (control, spiritual significance) reasons. Walking its vast perimeter helps one grasp the scale of the territorial claims and the organizational power of the communities that built it.

Oral Traditions and Memory Maps

Beyond the monumental earthworks, the most prevalent form of Indigenous cartography in the Ohio Valley was undoubtedly oral tradition. Stories, songs, and detailed narratives encoded critical geographical information: the location of fertile hunting grounds, safe river crossings, sources of flint or salt, and the routes connecting various communities. These "memory maps" were dynamic, living entities, adapted and reinforced through repeated telling and experiential learning.

Imagine a young Shawnee or Miami person learning the intricacies of the Scioto River valley not from a static drawing, but from a grandparent recounting a hunting journey, describing landmarks, the flow of the current, the changes in vegetation, and the stories associated with each bend in the river. Place names themselves were often descriptive, acting as miniature maps, identifying features like "place of abundant deer" or "where the rapids are dangerous." These oral traditions were incredibly robust, allowing for navigation across vast territories without the need for written charts, a testament to the power of collective memory and cultural transmission. While we cannot "visit" these oral maps directly, understanding their existence encourages us to listen to the landscape itself, to imagine the stories it could tell.

Petroglyphs and Rock Art: Etched Journeys

Less extensive but still significant are the petroglyphs and pictographs found in various locations across the Ohio Valley. While many depict spiritual beings or historical events, some undoubtedly served as route markers, territorial claims, or records of important journeys. For example, the Leo Petroglyph Site in Ohio features carvings of human and animal figures, some of which may represent specific clans or serve as warnings or directional signs along ancient trails. These offer glimpses into specific points along the larger cartographic network, providing micro-details within the grander scheme.

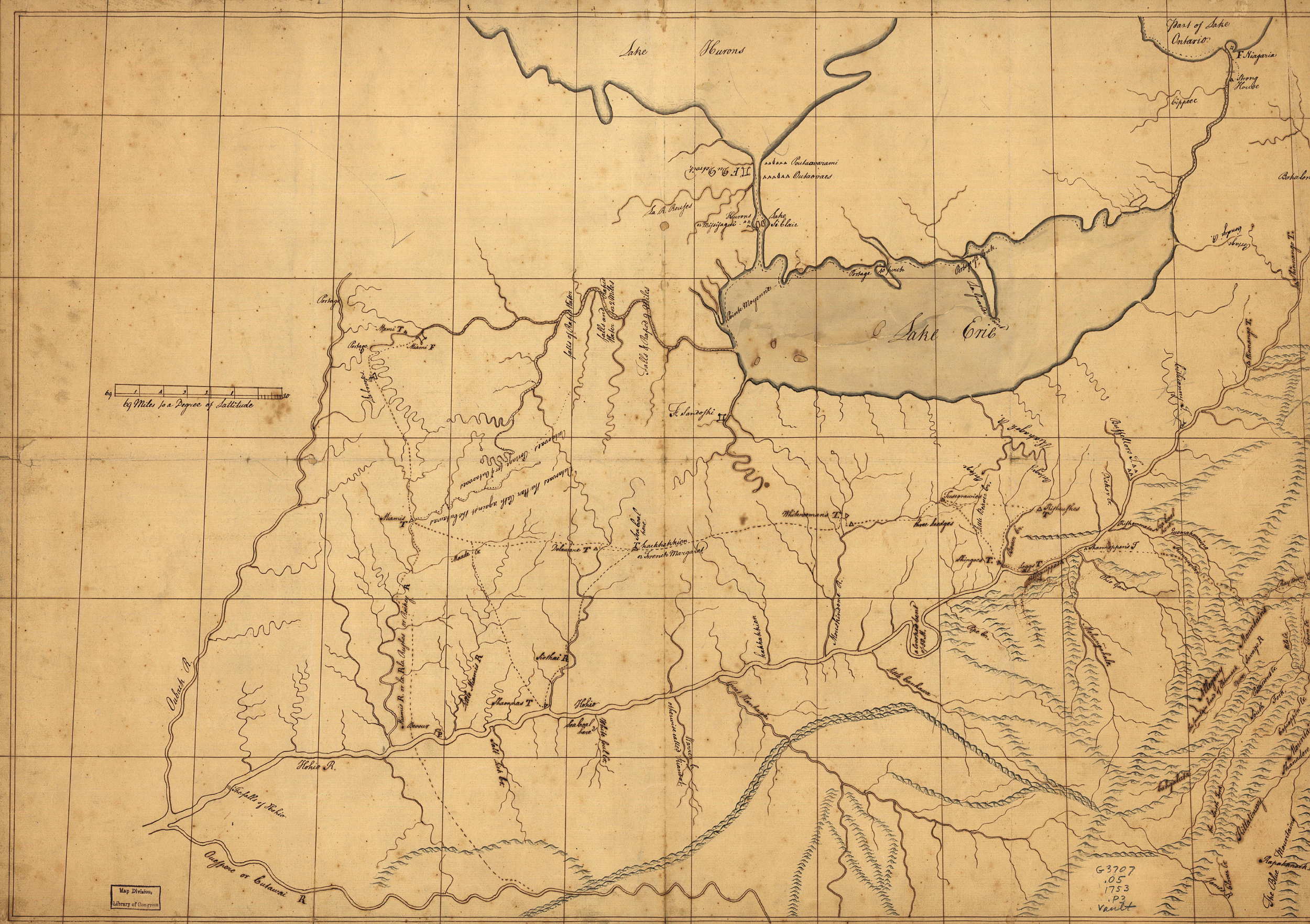

Indigenous Knowledge and European Cartography

When European explorers and settlers first entered the Ohio Valley, they were heavily reliant on Indigenous guides and their deep geographical knowledge. Many early European maps of the region, though drawn in a Western style, fundamentally incorporate Indigenous information. Native informants literally "mapped" the landscape for cartographers like John Filson, Lewis Evans, and Christopher Gist, indicating trails, river systems, and village locations. This highlights the practical utility and accuracy of Indigenous cartography, even as it was often reinterpreted and sometimes distorted by European perspectives and agendas. These hybrid maps serve as poignant reminders of the invaluable knowledge shared, often under duress, by Native peoples.

Experiencing the "Maps" Today: A Traveler’s Guide

For the modern traveler, understanding Native American maps of the Ohio Valley transforms a simple road trip into a profound historical expedition.

-

Visit the Earthworks: This is paramount.

- Newark Earthworks (Ohio): Walk the perimeter of the Octagon, marvel at the precision. The Ohio History Connection maintains an excellent interpretive center at the Great Circle Earthworks (part of the complex). Imagine the ceremonial processions, the astronomical observations.

- Serpent Mound (Ohio): Ascend the observation tower to grasp the full serpentine form. Walk along its length, feeling the subtle undulations and imagining its cosmic significance.

- Fort Ancient (Ohio): Explore the extensive walls and the interpretive center. Contemplate the vastness of this human endeavor and its strategic location.

- Mound City Group (Ohio): Part of the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, this site features numerous burial mounds within a rectangular enclosure. While not a "map" in the same way as the geometric earthworks, it represents a sacred landscape, a gathering of ancestors, and a focal point for spiritual journeys.

-

Engage with Museums and Cultural Centers:

- Ohio History Center (Columbus, OH): Offers comprehensive exhibits on Ohio’s Indigenous peoples, including artifacts and interpretations of their cultures and land use.

- The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art (Indianapolis, IN): While broader, it provides valuable context for the Indigenous cultures of the Midwest, including those connected to the Ohio Valley.

- Local museums and historical societies: Many smaller institutions in the region have exhibits on local Indigenous history, sometimes showcasing artifacts found near ancient trails or sites.

-

Hike Ancient Trails and Riverways: Many modern hiking trails follow ancient Indigenous routes. While the specific "map" details are gone, walking these paths allows for a visceral connection to the land and an appreciation for the challenges and beauty of ancient travel. Kayaking or canoeing on the Ohio River and its tributaries also offers a unique perspective, mimicking the primary arteries of ancient travel and trade.

-

Look Beyond the Obvious: Learn to "read" the landscape. Notice the lay of the land, the flow of rivers, the presence of specific plants or stone types. Imagine how these features would have been understood and utilized by Indigenous peoples. Consider how a specific hill might have been a lookout, a particular grove a sacred space, or a confluence of rivers a significant meeting point.

Challenges and Preservation

The legacy of Native American cartography in the Ohio Valley faces ongoing challenges. Many earthworks were destroyed by agriculture and urban development. The oral traditions were suppressed, and Indigenous languages, the very vessels of these memory maps, were often forbidden. However, significant efforts are underway by modern Indigenous communities, archaeologists, and conservationists to protect what remains, to interpret these sites respectfully, and to revitalize the understanding of this profound heritage. The UNESCO World Heritage designation for the Hopewell Ceremonial Earthworks is a testament to the global recognition of their significance.

Conclusion

To explore the Ohio Valley with an awareness of its Indigenous maps is to embark on a truly transformative travel experience. It’s to move beyond superficial tourism and connect with the profound layers of human history etched into the very fabric of the land. It’s an opportunity to see the world through a different lens – one that values connection, observation, and a deep, spiritual understanding of place. The Ohio Valley is not just a collection of historical sites; it is a living map, waiting for you to learn its language and decipher its ancient, enduring stories.