The lines on a map, often drawn with a cartographer’s dispassionate hand in distant government offices, rarely betray the tumultuous histories they encapsulate. Yet, to travel through the heart of the American West, particularly across the stark, beautiful expanses of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, is to confront these lines not as abstract demarcations, but as living scars and enduring testaments to a profound reshaping of land, culture, and identity. This isn’t merely a geographical journey; it’s an immersion into a landscape where every ridge, every sweep of prairie grass, whispers stories of treaties signed and broken, of forced removals, and of an unyielding spirit that defies the very boundaries imposed upon it.

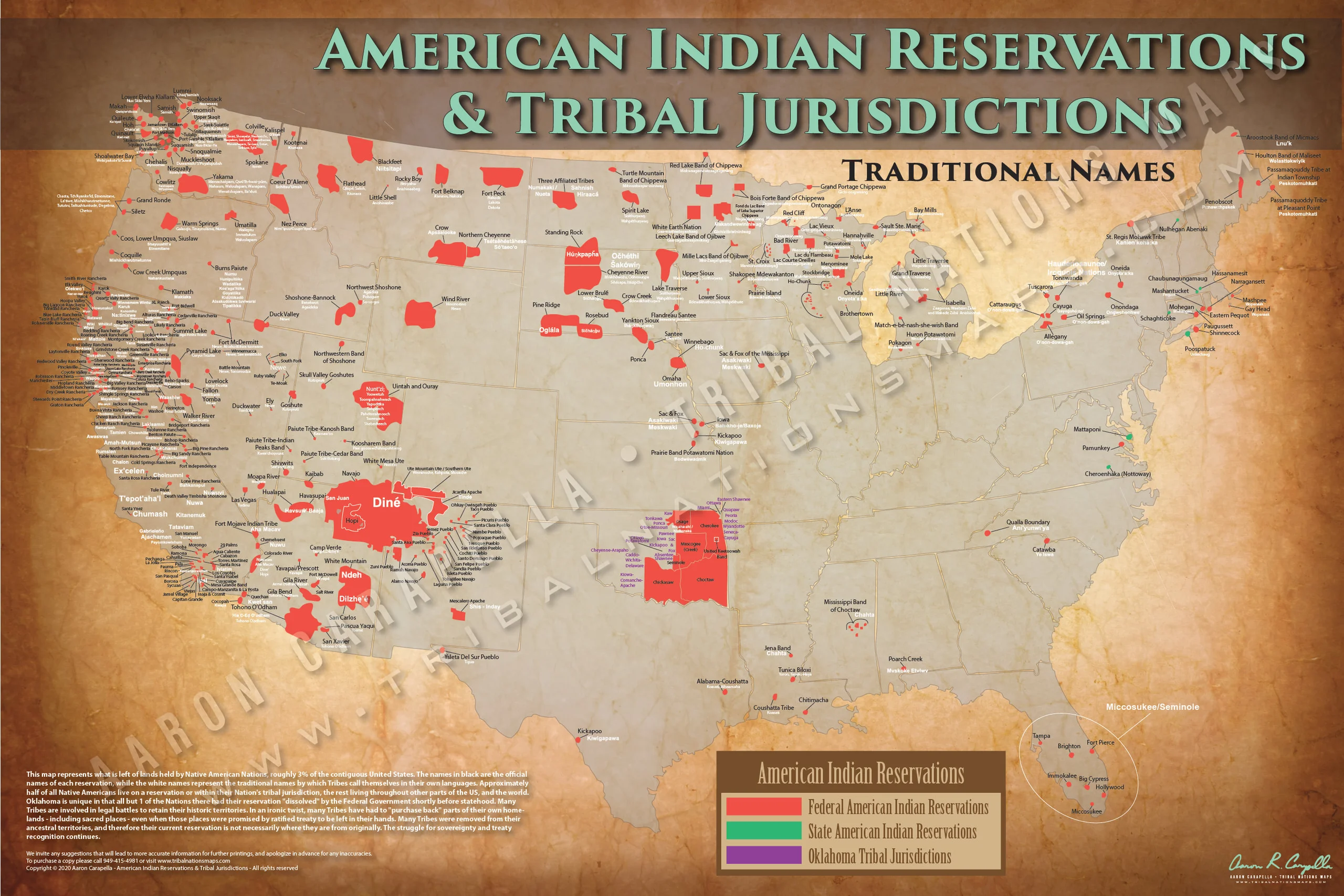

Pine Ridge, home to the Oglala Lakota Nation, is one of the largest and most historically significant reservations in the United States. Its establishment, like many others, was a direct consequence of the infamous Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, which initially promised a vast Great Sioux Reservation encompassing much of present-day South Dakota and parts of Wyoming and Nebraska. Subsequent gold rushes in the sacred Black Hills and persistent settler encroachment led to the gradual, often violent, reduction of this land base, culminating in the creation of smaller, fragmented reservations, including Pine Ridge, through maps that served as instruments of dispossession. These maps, meticulously detailing the shrinking territories, were not just geographical representations; they were political decrees, defining who belonged where, and crucially, who did not.

To understand Pine Ridge, one must first confront the sheer scale of the landscape itself. The reservation spans over 3,400 square miles, an area larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined, yet it feels even vaster, a sprawling tableau of mixed-grass prairie, rolling hills, and the dramatic, eroded formations of the Badlands National Park’s South Unit, which lies entirely within the reservation’s boundaries. Driving through this territory, the arbitrary nature of the lines becomes palpable. One moment you are on federal parkland, the next you cross an invisible threshold onto tribal land, though the geological majesty remains uninterrupted. The maps sliced through ecosystems, traditional hunting grounds, and spiritual sites, attempting to compartmentalize a people whose relationship with the land was holistic and unbounded.

The Badlands, particularly the Stronghold Table and Palmer Ridge areas within the South Unit, offer a breathtaking, almost alien beauty that paradoxically underscores the human history. Here, geological time is laid bare in layers of vibrant sediment, carved by wind and water into spires, buttes, and canyons. It is a landscape that demands quiet contemplation. For the Lakota, these lands are not merely geological wonders but ancestral homes, places of vision quests, healing, and deep spiritual connection. The very ruggedness that made them less desirable for agriculture by white settlers ironically preserved a degree of their traditional character, allowing the Lakota to maintain a foothold in a landscape that still speaks their language.

A visit to the Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge village provides a crucial window into the reservation’s complex history and its ongoing efforts to preserve culture and educate its youth. Established in 1888 by Jesuit missionaries, it represents a duality: an institution initially designed to assimilate Native children, yet one that has, over time, become a vital center for Lakota language and cultural revitalization. The Heritage Center at Red Cloud, housing an impressive collection of Lakota art and historical artifacts, offers a poignant narrative of resilience. Here, the maps of reservation establishment are not just historical documents; they are part of a larger story of survival, of adapting and reclaiming identity despite external pressures. The traditional regalia, the beadwork, the ledger art—all tell stories that transcend the boundaries drawn on paper, illustrating the richness and continuity of Lakota culture.

Beyond the major cultural centers, the true essence of Pine Ridge reveals itself in the smaller communities and along the quieter roads. Driving east from Pine Ridge village towards Wanblee or Kyle, the landscape softens into rolling grasslands dotted with small ranches, horses, and the occasional roadside stand selling frybread or crafts. These are the places where the reservation’s economic realities are most visible, where the legacy of underdevelopment and systemic challenges stemming from the reservation system are stark. The maps, in their creation of isolated, often resource-poor territories, inadvertently fostered conditions that continue to challenge the Oglala Lakota today. Yet, amidst these challenges, the sense of community, the pride in heritage, and the deep connection to family and land remain vibrant.

The historical maps, in their colonial intent, sought to define the Lakota as a static, bounded entity. However, the experience of traversing Pine Ridge teaches a different lesson: that culture is dynamic, and identity is not confined by lines. The annual Oglala Nation Powwow, held in July/August, is a powerful demonstration of this. It’s a vibrant explosion of color, sound, and movement, where traditional dances, drumming, and singing reaffirm Lakota identity in a collective celebration that transcends any imposed boundary. Here, the youth learn from elders, traditions are passed down, and the spirit of the people, far from being contained, radiates outward. It’s a direct rebuttal to the idea that a people can be confined or their spirit diminished by arbitrary lines on a governmental map.

For the conscientious traveler, visiting Pine Ridge is not a typical vacation. It is an educational journey, a call to witness, and an opportunity for respectful engagement. It requires an open mind, a willingness to listen, and an understanding of the profound historical weight of the place. There are opportunities for guided tours with local Lakota guides who can offer invaluable insights into the land, history, and contemporary life. Supporting local businesses, artists, and cultural initiatives is paramount. Places like the Wounded Knee Massacre site, a solemn and sacred memorial, demand reverence and quiet reflection, reminding visitors of one of the darkest chapters in American history, directly linked to the consequences of these territorial disputes and the maps that failed to protect Native lands and lives.

In conclusion, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is far more than just a dot on a modern map. It is a living, breathing testament to the profound and often painful legacy of Native American reservation establishment. It is a place where the lines drawn on historical government maps continue to shape daily life, yet simultaneously fail to contain the rich culture, resilience, and spiritual connection of the Oglala Lakota people. A journey here is not just about seeing a landscape; it’s about understanding the deep human stories etched into it, recognizing the enduring impact of those early maps, and witnessing the vibrant continuation of a culture that thrives despite them. It is an essential, transformative experience for anyone seeking to understand the true, complex tapestry of American history and the enduring spirit of its first peoples.