Forget the gridlines and GPS coordinates. To truly understand a landscape, to move beyond merely occupying a space and instead inhabit a place, we must recalibrate our internal compass. For millennia, Native American peoples have navigated, understood, and mapped their territories not with lines on paper, but with stories, ceremony, seasonal movements, and an intimate, reciprocal relationship with the land itself. This profound, often invisible, cartography offers a revolutionary way to travel, transforming a simple journey into an act of deep cultural and ecological engagement.

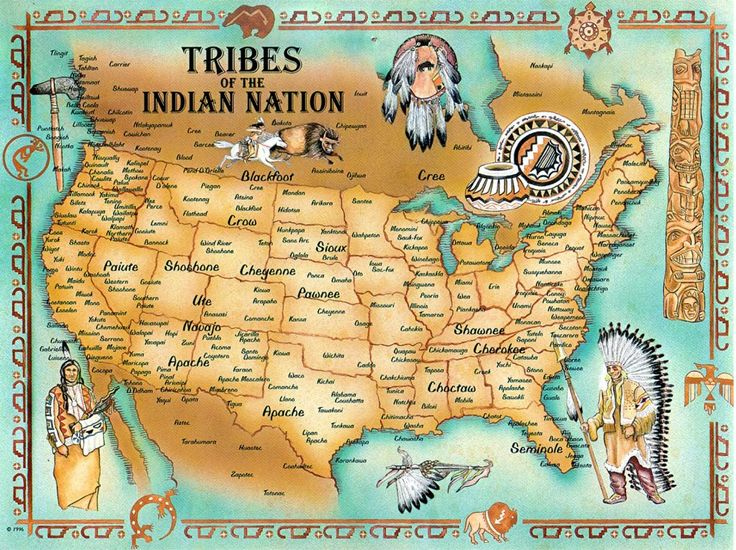

Let’s ground this concept in a tangible location: The Black Hills of South Dakota. Known to the Lakota as Paha Sapa, "the hills that are black," this region is a microcosm of America’s complex relationship with its indigenous past and present. It is simultaneously a U.S. National Forest, a popular tourist destination brimming with iconic monuments, and the sacred ancestral heartland of the Lakota, Cheyenne, Kiowa, and other Plains tribes. Traveling through the Black Hills with a consciousness informed by Native American mapping principles isn’t just a different way to see; it’s a different way to be in the landscape.

Beyond Colonial Cartography: The Indigenous Map

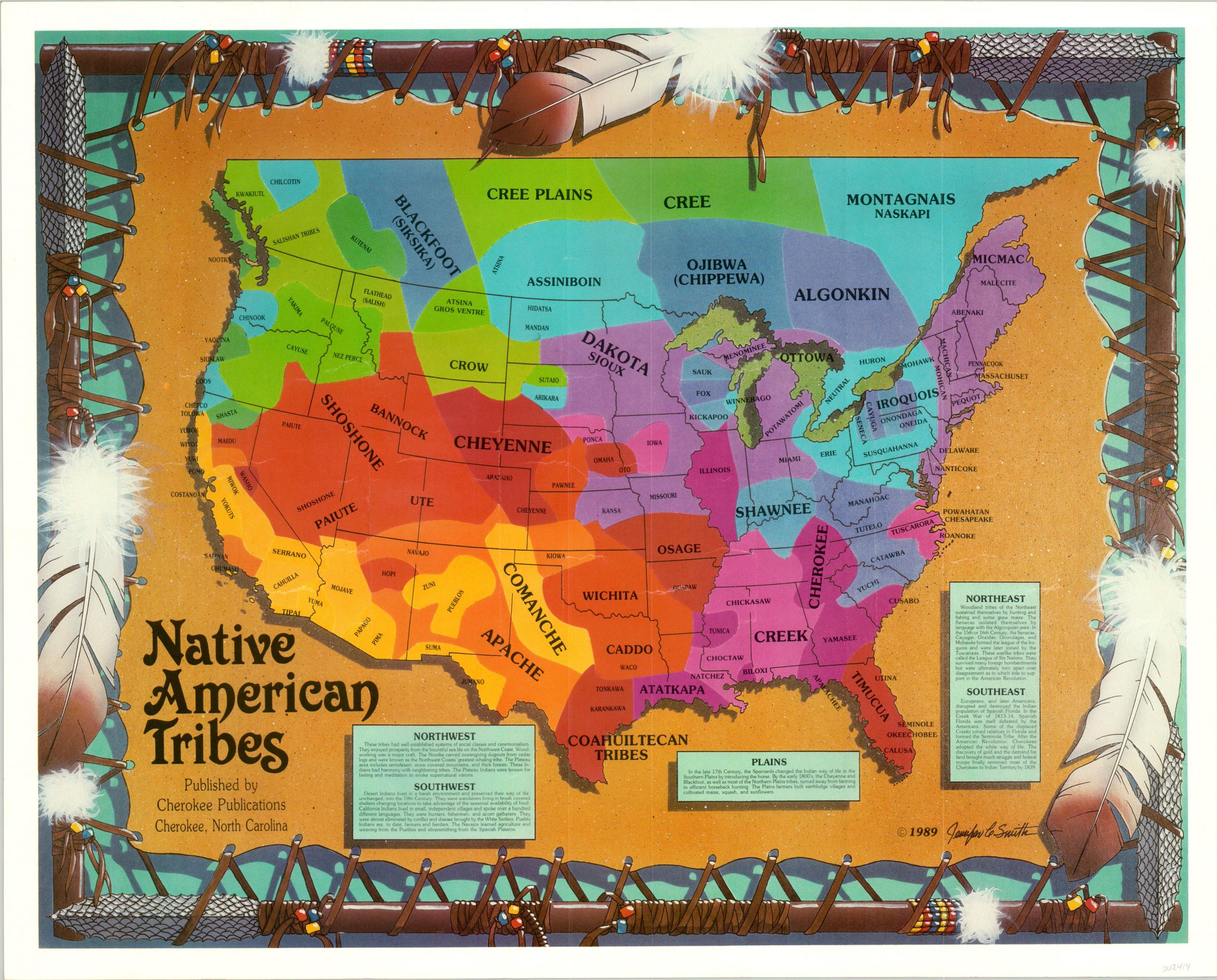

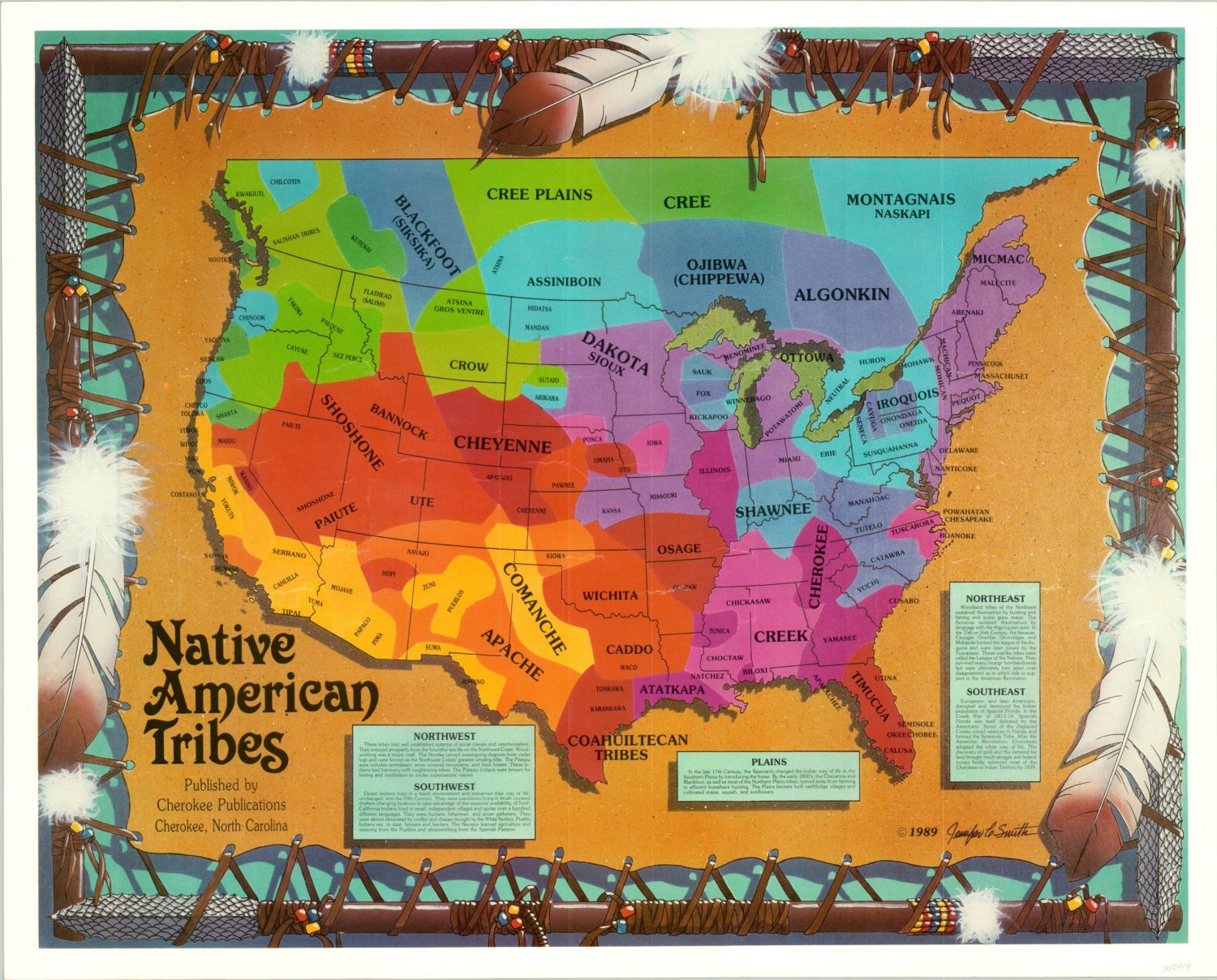

Western mapping, from its earliest forms, has been a tool of control, division, and ownership. It flattens a dynamic, living world into static, two-dimensional representations, prioritizing boundaries, resources, and often, a colonial gaze. Native American "maps," however, operate on entirely different principles. They are not static. They are dynamic, multi-layered repositories of knowledge, embedded in oral traditions, songs, dances, place names, and sacred sites.

Imagine a map that tells you not just where a river flows, but who fished there seasonally, what plants grew along its banks and their medicinal uses, which stars guided night travelers along its course, and what spiritual significance its confluence held. These are maps of memory, of relationship, of reciprocal obligation between humans and the more-than-human world. They trace ancestral migrations, mark vision quest sites, record historical events through landscape features, and delineate seasonal hunting grounds with an intimacy that modern cartography can never replicate.

For the Lakota, Paha Sapa is not merely a geographical feature; it is their spiritual genesis, the place where the Creator breathed life into the first people. It is the sacred center of their universe, a living entity interwoven with their identity. The peaks, valleys, caves, and waters within the Black Hills are not just scenic vistas but altars, ceremonial grounds, and storytellers. This deep understanding, this indigenous map, is what every traveler to the Black Hills has the opportunity to uncover.

The Black Hills: A Contested Sacred Center

The Black Hills are breathtaking. Rolling pine-clad mountains, dramatic granite spires, deep canyons, and vast prairie expanses define its geology. Within its boundaries lie Wind Cave National Park, Custer State Park, Bear Butte State Park, and the iconic (and controversial) Mount Rushmore. The U.S. Forest Service manages the majority as the Black Hills National Forest, emphasizing recreation and resource management.

But for the Lakota, every inch of this land reverberates with history and prophecy. The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty explicitly recognized the Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation. Yet, the discovery of gold swiftly led to its illegal seizure by the U.S. government, sparking generations of legal battles and enduring injustice. To this day, the Lakota have refused a multi-billion dollar settlement, insisting on the return of their sacred land.

Traveling through the Black Hills with this indigenous map in mind means seeing beyond the tourist brochure. It means understanding that the beauty you witness is not just natural splendor, but a landscape infused with spiritual power and profound historical pain.

Navigating with Indigenous Awareness: A Traveler’s Guide

So, how does one apply this indigenous "mapping" perspective to a travel experience in the Black Hills? It’s not about finding a literal Lakota map in a gift shop. It’s about shifting your mindset, asking different questions, and seeking out opportunities for deeper engagement.

-

Acknowledge and Learn the True History: Before you go, or as you arrive, seek out resources from tribal nations themselves. Tribal websites (e.g., Oglala Lakota Nation, Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe), cultural centers, and museums (like The Journey Museum & Learning Center in Rapid City, which has a strong Native American exhibit) are invaluable. Understand the treaties, the broken promises, and the ongoing struggles for land and sovereignty.

-

Visit Sacred Sites with Reverence:

- Bear Butte State Park (Mato Paha): East of Sturgis, Bear Butte is one of the most sacred sites for Plains tribes. It is a place of prayer, vision quests, and ceremonies. When you hike its trails, you will see prayer flags and offerings tied to trees. Understand that you are entering a living church. Be respectful, stay on marked trails, and do not disturb offerings. This is not just a hike; it’s a pilgrimage.

- Wind Cave National Park (Pe Sla): This ancient cave system holds deep spiritual significance for the Lakota as a place of emergence, where the first humans are said to have entered the world. Ranger-led tours offer geological insights, but carry with you the knowledge of its profound cultural importance. The rolling prairie above the cave, known as Pe Sla, is also a sacred ceremonial site.

- Black Elk Peak (formerly Harney Peak): The highest point in South Dakota, Black Elk Peak is a spiritual focal point, where the Oglala Lakota holy man Black Elk had his Great Vision. While the name change from Harney Peak (a military general involved in massacres) was a step toward reconciliation, its sacred status remains. Hiking to its summit, consider the generations who have sought spiritual insight from this vantage point.

-

Engage with Living Culture:

- Pine Ridge Indian Reservation: While outside the direct Black Hills National Forest, Pine Ridge is home to the Oglala Lakota and is essential for understanding contemporary Lakota life. Visiting the Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, or exploring the Wounded Knee Massacre site (with appropriate respect and guidance), provides a stark, yet vital, contrast to the more developed tourist areas. Support tribal businesses and artists.

- Crazy Horse Memorial: A monumental, ongoing sculpture project, Crazy Horse Memorial is a privately funded, tribally led effort to honor the legendary Lakota leader and the spirit of all Native American people. It stands in direct contrast to Mount Rushmore, which the Lakota view as a desecration of their sacred land. Visiting Crazy Horse means engaging with a living testament to indigenous resilience and pride.

-

Listen to the Land’s Stories: Indigenous maps are often told through stories. As you drive through the Black Hills, imagine the landscape not as an empty canvas, but as a vast library. Every rock formation, every stream, every stand of trees holds a narrative. How did this canyon form, not just geologically, but in the oral traditions of the people? What animal spirits are associated with these forests? This approach encourages slower, more observant travel. Look for interpretive signs that include Native American perspectives.

-

Support Ethical Tourism and Tribal Economies: Look for opportunities to purchase authentic Native American art, crafts, and food directly from tribal artists and businesses. This ensures that your travel dollars directly benefit indigenous communities and help preserve cultural traditions. Attend powwows or cultural events if invited and do so with respect and an open mind.

-

Practice Respectful Outdoor Ethics: Beyond "Leave No Trace," consider "Leave a Good Impression." This means respecting cultural sites, asking permission before taking photos of people, and understanding that some areas may be culturally sensitive or off-limits. Your presence as a visitor should be an act of humility and respect.

The Deeper Journey

Traveling the Black Hills through the lens of Native American maps is not just an intellectual exercise; it’s an embodied experience. It transforms a scenic drive into a journey through sacred history. It shifts your perception from seeing mountains as inert objects to recognizing them as living entities with stories, spirit, and profound meaning.

This indigenous cartography offers a pathway to a more conscious, ethical, and enriching form of travel, not just in the Black Hills, but anywhere. It reminds us that every landscape we visit has a deeper history, a multitude of meanings beyond what is printed on our modern maps. By seeking out these indigenous perspectives, we don’t just explore new places; we explore new ways of understanding our shared world and our place within it.

The Black Hills, then, are not just a destination for outdoor adventure or historical monuments. They are a classroom, a spiritual sanctuary, and a testament to enduring indigenous sovereignty and cultural resilience. By consciously engaging with the invisible maps of the Lakota and other Native nations, travelers can move beyond being mere tourists and become respectful witnesses, connecting with a profound legacy that continues to shape this remarkable and sacred land. Your journey through Paha Sapa will be immeasurably richer for it.