For many travelers, California’s historic missions evoke images of serene adobe courtyards, ringing bells, and a romanticized past. The Spanish colonial structures, stretching from San Diego to Sonoma, are often presented as picturesque relics of a bygone era, their well-trodden paths inviting visitors to step back in time. Yet, to truly understand these sites and the landscapes they inhabit, a deeper, more profound journey is required—one that moves beyond the colonial narrative to explore the invisible maps of the Indigenous peoples who lived on these lands for millennia before the missions arrived.

This article invites you on a different kind of mission trail, a journey to uncover the layered histories and enduring presence of Native American cultures, specifically through the lens of their unique cartographies and how they intersect, and often clash, with the imposed geometry of the mission system. Our focus is not on a single mission, but on the very concept of place as understood by Native Americans, and how that understanding can enrich your travel experience along the California coast and beyond.

The Invisible Maps: Indigenous Cartography Before the Missions

Before the Spanish padres and soldiers arrived, establishing their rigid grid of missions, presidios, and pueblos, the lands now known as California were a mosaic of diverse Indigenous nations. Over 300 distinct groups, speaking more than 100 languages, thrived in complex, interconnected societies. Their relationship with the land was not one of ownership in the European sense, but of stewardship, reciprocity, and deep spiritual connection.

Their "maps" were not static lines on parchment but living narratives woven into the very fabric of existence. These cartographies were dynamic, multi-sensory, and passed down through generations via oral traditions, songlines, ceremonial practices, and intimate knowledge of the landscape. For the Kumeyaay of the south, the Tongva (Gabrieleño) of the Los Angeles basin, the Chumash of the central coast, or the Ohlone of the Bay Area, a map was a story. It encoded the locations of sacred sites, seasonal foraging routes, water sources, ancestral burial grounds, and the boundaries of kinship and trade networks.

Imagine a map made of constellations guiding seasonal migrations, of the scent of wildflowers indicating a fertile harvesting ground, of the sound of a specific creek marking a territorial boundary. Place names, often describing a physical feature or an event that occurred there, were mnemonic devices, loaded with ecological and historical information. Rock art, such as the intricate polychrome paintings of the Chumash found in places like the Carrizo Plain, served not just as spiritual expressions but as records of cosmology, astronomical observations, and possibly even territorial markers or migration routes. These were sophisticated, deeply integrated systems of knowing and navigating their world, a world fundamentally altered by the arrival of the missions.

The Missions: Imposed Geometries and Disrupted Landscapes

The 21 California missions, established between 1769 and 1833, were not merely religious outposts; they were instruments of colonial expansion, designed to assimilate Indigenous populations into Spanish culture, labor systems, and Catholicism. Each mission was strategically placed approximately a day’s ride apart, creating a linear "El Camino Real" that imposed a new, European-centric map onto an ancient, Indigenous landscape.

From a Native American perspective, the missions represent a profound disruption. They were built on ancestral lands, often near existing villages, exploiting natural resources and vital water sources. The forced relocation of Indigenous peoples, often referred to as "neophytes," into the missions severed their connection to their traditional territories, their invisible maps rendered useless or dangerous. Their sacred sites were desecrated, their languages suppressed, and their traditional lifeways dismantled in favor of agricultural labor, craft production, and Catholic worship.

The architectural uniformity of the missions—the quadrangular courtyards, the adobe churches, the workshops—reflected a desire for order and control, a stark contrast to the organic, adaptable structures of Native villages. This physical imposition was mirrored by a conceptual one: the European concept of land ownership, with its fences and property deeds, replaced the Indigenous understanding of shared stewardship. The very act of building the missions was an act of mapping, drawing new boundaries and asserting new claims over lands that had been stewarded by Native peoples for millennia.

Your Journey: Tracing Both Maps on the Mission Trail

To truly engage with the California missions and the rich, complex history they embody, a conscious effort must be made to seek out and understand the Indigenous perspective. This means looking beyond the curated beauty of the adobe walls and asking: Whose land is this? What stories are untold here?

Here’s how to embark on a journey that honors both the visible mission architecture and the invisible Native American maps:

1. Re-evaluating the Mission Sites Themselves:

Many mission sites are beginning to incorporate Indigenous voices and histories, though progress varies. When you visit:

- Look for Interpretive Panels: Seek out exhibits that specifically address the experiences of the Indigenous people associated with that particular mission. Do they acknowledge forced labor, disease, and cultural suppression? Do they feature contemporary tribal voices?

- Mission San Juan Capistrano (Acjachemen/Juaneno): While famous for its swallows and "Great Stone Church," actively seek out information about the Acjachemen people. Their cultural center or events may offer deeper insights.

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa (Chumash): This mission, like many, sits on historically Chumash land. Look for any signage that acknowledges their presence before, during, and after the mission period.

- Mission Santa Inés (Chumash): The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians has a strong presence in the area. While the mission tells its story, consider how their perspective might differ.

2. Visiting Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums:

This is perhaps the most crucial step for understanding Native American maps and perspectives. These institutions are curated by and for Indigenous communities, offering authentic voices and interpretations of history, culture, and their enduring connection to the land.

- Barona Cultural Center & Museum (Lakeside, near San Diego): Run by the Barona Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay), this award-winning museum offers a comprehensive look at the history, culture, and resilience of the Kumeyaay people. It provides vital context for understanding the Indigenous experience in Southern California, including the impact of nearby missions.

- Santa Ynez Chumash Museum & Cultural Center (Santa Ynez): Located on the Santa Ynez Chumash Reservation, this center is dedicated to preserving and sharing Chumash history and culture. It offers a direct connection to the living descendants of the people who inhabited the central coast for millennia, providing a powerful counter-narrative to the mission story.

- California Indian Museum and Cultural Center (Santa Rosa): While not tied to a single mission, this center offers a broader perspective on the diverse Indigenous cultures of California, providing essential context for understanding the pre-contact and post-contact histories across the state.

- Tongva Cultural Center (near Los Angeles): As the original inhabitants of the Los Angeles basin, the Tongva (Gabrieleño) people have a rich history entwined with Missions San Gabriel Arcángel and San Fernando Rey de España. Seek out their cultural initiatives to learn about their ancestral maps and ongoing efforts to reclaim their heritage.

3. Exploring the Landscape Beyond the Adobe:

Remember that Indigenous maps are deeply rooted in the land itself. To truly see these maps, you must look beyond the mission compounds.

- Sacred Sites and Natural Landmarks: Research significant natural landmarks in the areas you visit. Mountains, rivers, and specific rock formations often hold deep spiritual and historical significance for Native peoples. For example, the Carrizo Plain National Monument in central California offers a chance to see ancient Chumash rock art, providing a direct visual link to their ancestral mapping of the landscape and cosmology.

- Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK): Learn about the plants and animals native to the region. Indigenous peoples possessed vast knowledge of their ecosystems, using plants for food, medicine, and tools. Understanding TEK helps to reconstruct their intricate relationship with the land and the "maps" that guided their sustainable practices.

- Place Names: Pay attention to surviving Indigenous place names (e.g., Malibu, Yosemite, Sonoma). These names often carry deep meaning and can be fragments of ancient maps, telling stories about the land that predate colonial naming conventions.

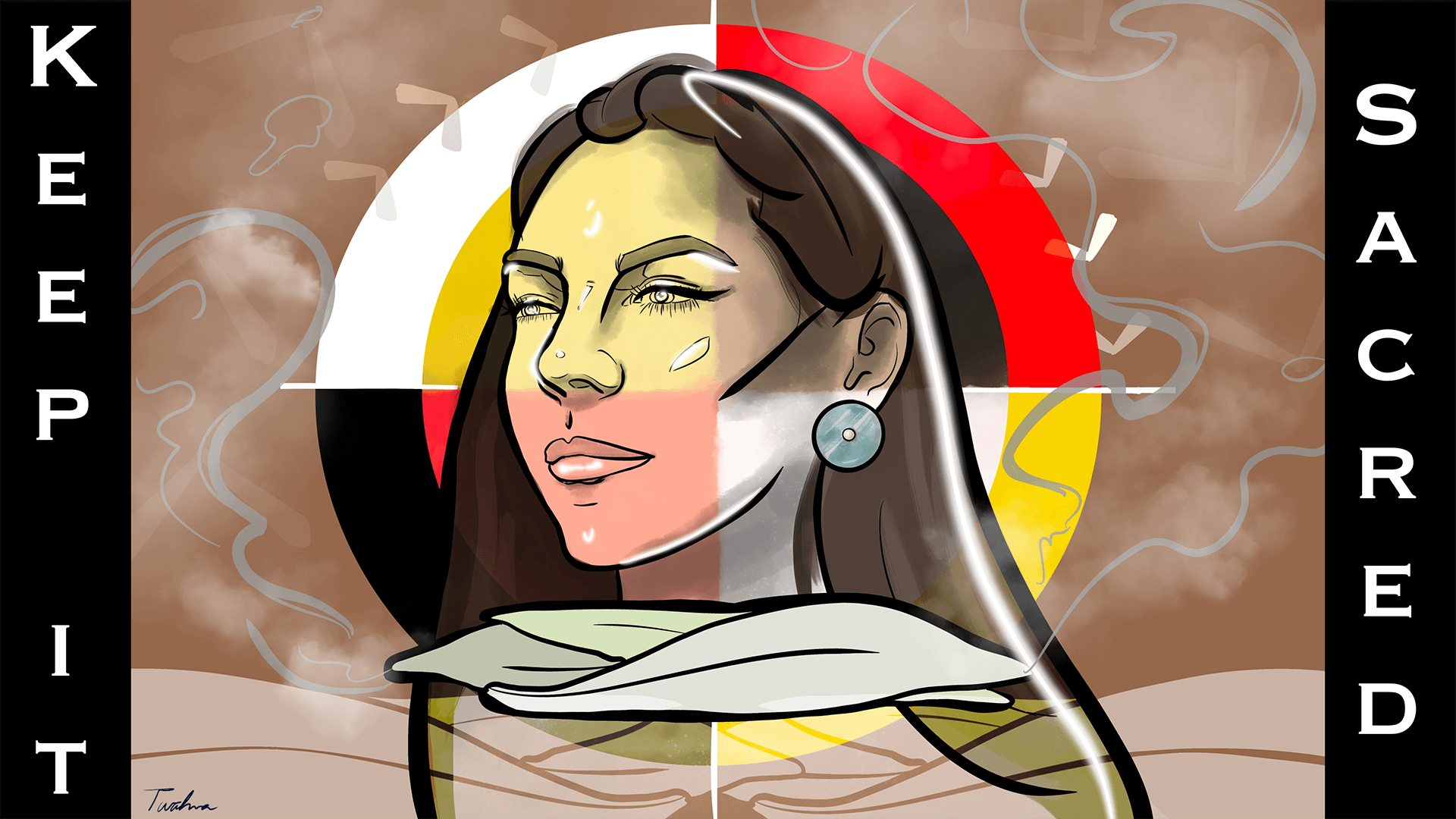

4. Engaging with Contemporary Indigenous Voices:

The mission era is not merely a historical footnote for California’s Native Americans; it is a living legacy. Seek out opportunities to engage with contemporary Indigenous artists, scholars, and community leaders. Many tribes host cultural events, lectures, and workshops that offer invaluable insights into their continuing presence and resilience. Supporting Indigenous-owned businesses and organizations also contributes directly to the revitalization of their cultures.

A Call for Conscious Exploration

Traveling the California Mission Trail with an awareness of Native American maps transforms a picturesque historical tour into a profound exploration of layered histories, cultural resilience, and ongoing struggles for recognition and justice. It encourages you to ask critical questions, to listen for the voices that have often been silenced, and to see the land through multiple lenses.

By consciously seeking out the Indigenous perspectives, by understanding that the missions were not built on empty land but on vibrant, ancient territories, you gain a far richer, more honest, and ultimately more respectful understanding of California’s past and present. Your journey becomes not just a travel experience, but an act of empathy and acknowledgement, helping to ensure that the invisible maps of California’s first peoples are seen, remembered, and honored for generations to come. This is the true mission of understanding—to connect with the enduring spirit of the land and its original inhabitants.