Standing atop Monks Mound at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, the wind whispers tales not just of the city that once thrived beneath your feet, but of the vast, intricate network of human movement that brought it into being and eventually saw its people disperse across the continent. This isn’t just a collection of ancient earthworks; it’s a monumental, physical record – a living map – of historical population movements in North America, predating European contact by centuries.

Cahokia, near modern-day St. Louis, Missouri, was the largest pre-Columbian city in what is now the United States, a sprawling metropolis that, at its peak around 1050-1200 CE, housed an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 people within its core, with perhaps another 30,000 in surrounding satellite communities. To understand Cahokia is to grapple with the sheer scale of human ambition and organization, and critically, the dynamic flow of populations that converged here. This site doesn’t offer neatly drawn parchment maps; instead, it presents an archaeological landscape that, through careful interpretation, reveals the movements of people as clearly as any modern cartographic projection.

The initial "mapping" of Cahokia’s population influx began long before its zenith. The fertile floodplains of the Mississippi River, a natural superhighway, acted as a magnet, drawing diverse groups of people from across the Midwest and Southeast. These early settlers, ancestors of the Mississippian culture, brought with them sophisticated knowledge of agriculture, especially maize cultivation, which allowed for unprecedented population density. Their "maps" were not drawn on paper but existed in oral traditions, shared knowledge of river currents, forest trails, and fertile hunting grounds. They understood the seasonal movements of game, the best places to fish, and the rhythms of the land – all critical information for successful migration and settlement. The very act of choosing this specific location, at the confluence of major waterways and rich agricultural lands, speaks to a collective understanding of geography and resources that enabled significant population aggregation.

The rise of Cahokia was a story of consolidation, a period when diverse groups, perhaps speaking different dialects and holding varying cultural practices, coalesced into a complex, stratified society. The monumental construction of over 120 mounds, including the colossal Monks Mound, required an immense, coordinated labor force – a testament to a highly organized society capable of directing tens of thousands of individuals. This process of urban growth and mound building itself can be seen as a form of spatial mapping, where labor was allocated, communities were organized around central plazas, and a distinct urban footprint was etched onto the landscape. Archaeological excavations reveal evidence of distinct neighborhoods, craft specialization areas, and ceremonial spaces, all suggesting a meticulously planned city that grew as people moved in, settled, and contributed to its development. The very act of bringing raw materials – chert from distant quarries, copper from the Great Lakes, shells from the Gulf Coast – to Cahokia demonstrates the extensive trade networks that pulled people and resources towards this central hub, forming economic "maps" of interaction and movement.

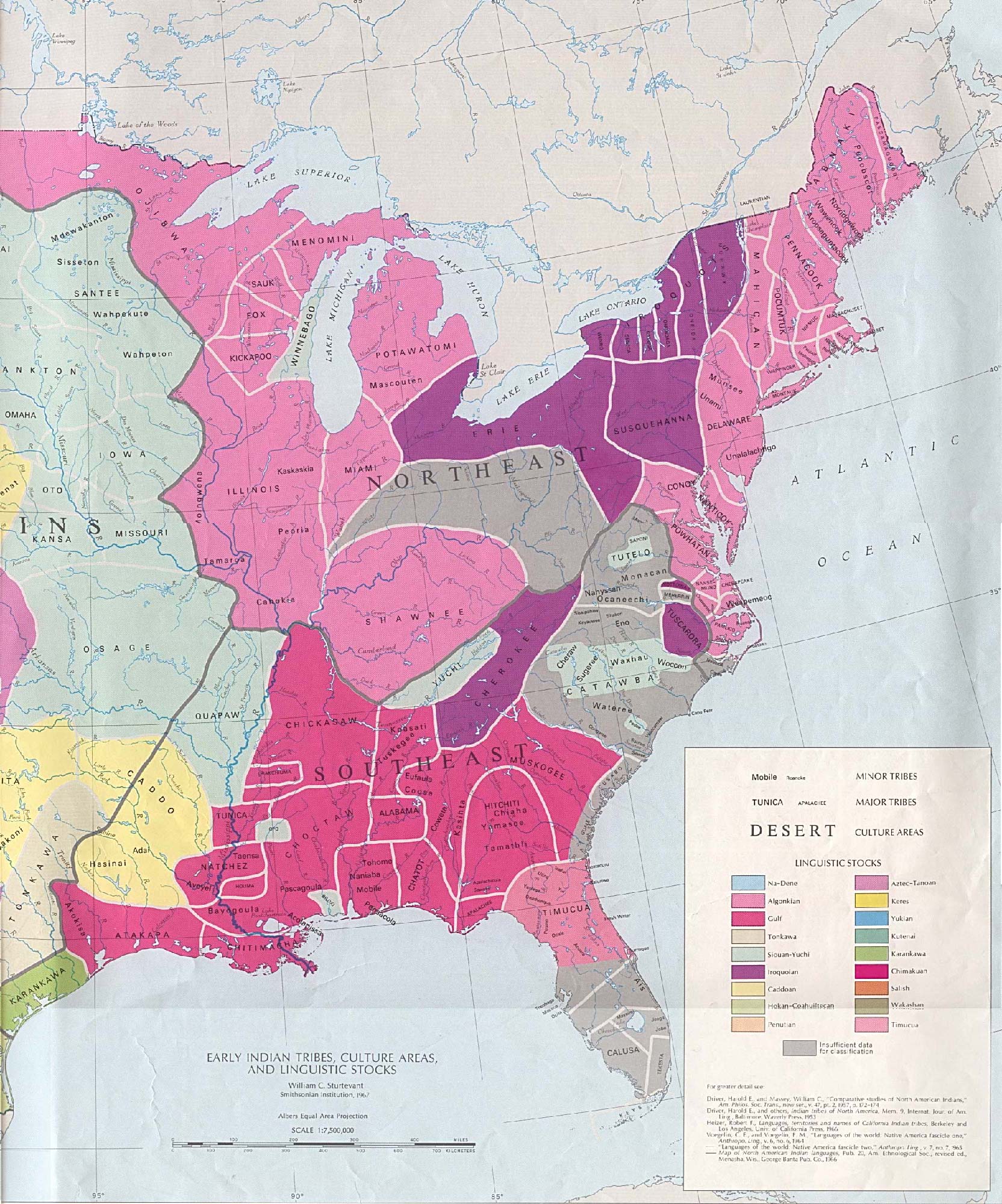

Perhaps even more compelling for understanding population movements is the eventual decline and dispersal of Cahokia’s inhabitants. By around 1200-1300 CE, the city began to empty, and by 1400 CE, it was largely abandoned. The reasons are still debated: environmental degradation, deforestation, resource depletion, climate change, social upheaval, or even disease are all plausible factors. Regardless of the exact cause, the archaeological record meticulously "maps" this exodus. The cessation of mound building, the change in pottery styles, the dwindling refuse piles – these are all indicators of a population in flux, packing up and moving on. The people didn’t simply vanish; they dispersed, becoming ancestors to many of the Native American nations we know today, including the Osage, Quapaw, Omaha, Ponca, Kansa, Caddo, and Wichita. Their movements away from Cahokia are traced through shared cultural practices, linguistic connections, and the presence of Mississippian cultural traits in later archaeological sites across the Midwest and Southeast. The landscape itself, with its scattered remnants of smaller settlements that rose and fell in the centuries following Cahokia’s decline, tells a story of constant adaptation and migration.

Visiting Cahokia today offers a profound, visceral connection to these ancient population movements. The sheer scale of Monks Mound, the largest earthwork in the Americas, is breathtaking. Climbing its wooden staircase to the summit, you gain a panoramic view of the Grand Plaza, the smaller mounds, and the surrounding floodplains. From this vantage point, it’s possible to visualize the bustling city that once stood here, the canoes plying the nearby waterways, and the footpaths radiating outwards like spokes from a wheel, connecting Cahokia to its satellite communities and distant trade partners. This elevated perspective literally provides a "map" of the ancient city and its sphere of influence, inviting contemplation of the vast journeys people undertook to reach this place and the equally significant journeys they embarked on when they left.

The interpretive center at Cahokia is crucial for translating the physical landscape into comprehensible "maps" of historical movement. Here, modern archaeological cartography comes to life through detailed site plans, topographical maps generated by LiDAR and GIS, and exhibits showcasing the distribution of artifacts. These visual aids allow visitors to understand how archaeologists trace population density, settlement patterns, and trade routes. Interactive displays explain the various theories for Cahokia’s rise and fall, illustrating how environmental factors or social dynamics influenced the movement of people into and out of the region. The center connects the abstract data to the human story, linking the ancient residents to their modern descendants and emphasizing the continuity of Indigenous presence in North America despite countless historical shifts.

Walking the various trails that crisscross the site, past the smaller mounds like Mound 72 (a significant burial mound), or exploring the reconstructed Woodhenge – a sophisticated solar calendar – you become acutely aware of the deep connection the Mississippian people had to their environment and the cosmos. Woodhenge, in particular, speaks to an intricate understanding of seasonal cycles, which in turn governed agricultural practices, hunting seasons, and ultimately, the rhythms of life that dictated where and when people moved. These ancient observatories and structures were not just static monuments; they were living tools that informed the movements and decisions of a vast population.

Beyond the specific archaeological interpretations, Cahokia also serves as a potent reminder of the broader concept of Native American cartography. Indigenous peoples across the continent possessed sophisticated ways of understanding, remembering, and conveying geographical information. While not always expressed as drawn maps in the European tradition, their "maps" were embedded in oral histories, epic narratives, ceremonial practices, and mnemonic devices. Landscape features themselves often served as markers in these mental or communal maps, guiding journeys, defining territorial boundaries, and commemorating historical events, including migrations. Cahokia, as a physical manifestation of a major population center and its subsequent dispersal, embodies this Indigenous understanding of place and movement. The very earthworks are a historical document, a three-dimensional map crafted by generations of people, telling a story of convergence, flourishing, and divergence that spans centuries.

To visit Cahokia is to undertake a journey into the heart of North America’s deep past, a past rich with complex societies and dynamic population movements that shaped the continent long before written history began for European settlers. It challenges simplistic narratives of static Indigenous cultures, revealing instead a vibrant tapestry of migration, innovation, and adaptation. It is a powerful reminder that the land itself holds the memory of these movements, and by engaging with sites like Cahokia, we can begin to decipher the profound, unwritten maps of the people who truly built and shaped this continent. It’s an essential pilgrimage for anyone seeking to understand the deep, living history of human migration and resilience.