The dust of Chaco Canyon settles not just on your boots, but deep into your soul, carrying with it echoes of an ancient civilization whose understanding of their world transcended mere lines on parchment. Forget conventional cartography; the Native American maps of Chaco Canyon are etched into the very landscape, in the alignment of colossal stone structures, the invisible paths of celestial bodies, and the wisdom passed down through generations. To visit Chaco is not merely to tour ruins; it is to step into a living, breathing map, a testament to unparalleled ingenuity and a profound connection to the cosmos.

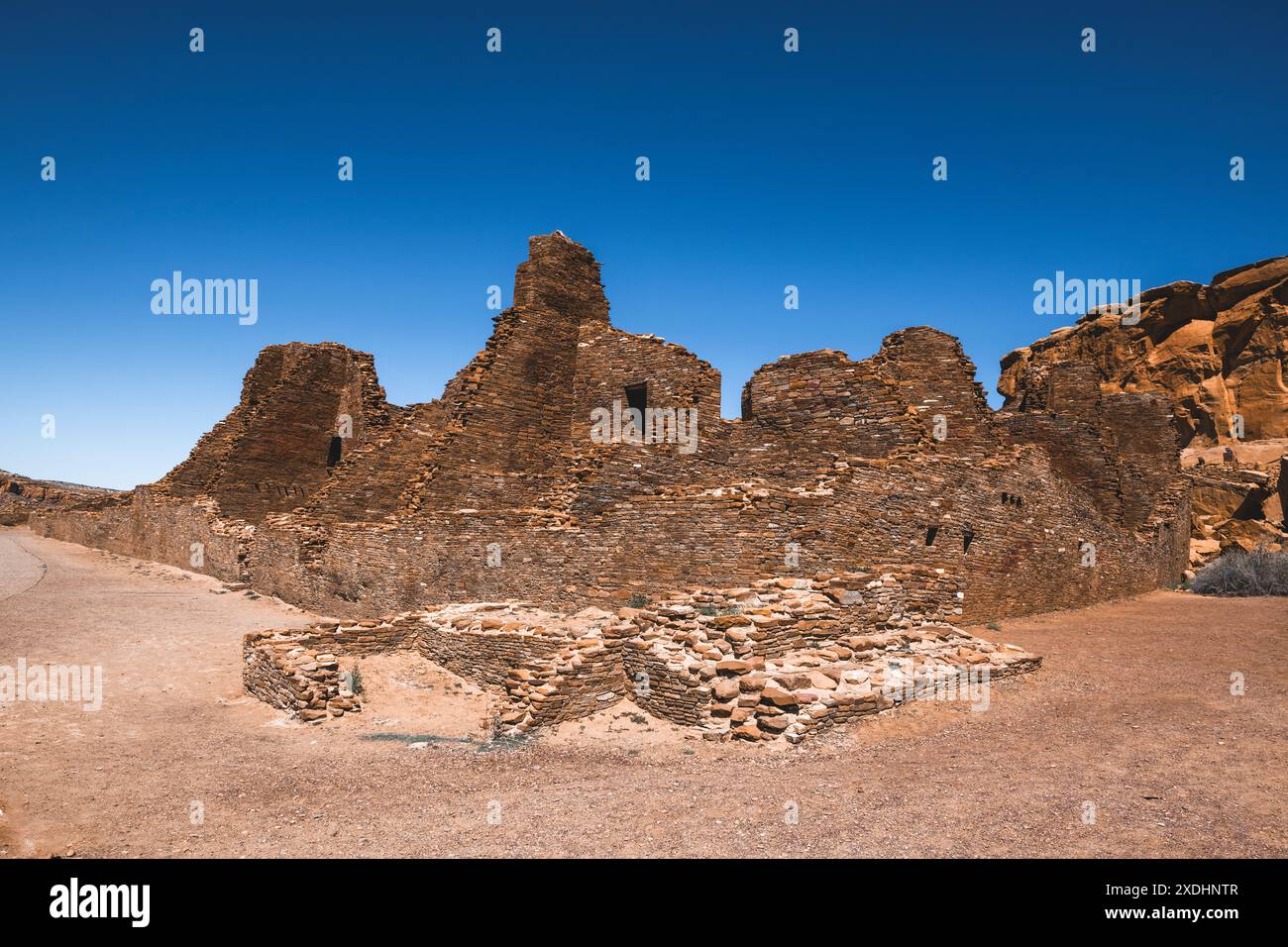

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, nestled in a remote, high desert basin of northwestern New Mexico, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site that served as a major center of Ancestral Puebloan culture between 850 and 1250 CE. It’s a place that demands effort to reach – a long, often unpaved drive down dusty roads – but the journey itself is part of the initiation. As the landscape slowly transforms, shedding signs of modern civilization, a sense of profound isolation and anticipation builds. Then, the canyon opens, revealing the monumental "Great Houses" that stand as silent sentinels, defying the arid environment and challenging our perceptions of ancient capabilities.

These Great Houses – Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, Kin Kletso, Hungo Pavi, and others – are the primary features of Chaco’s indigenous mapping system. They are not random settlements but meticulously planned, multi-story complexes built with astronomical precision. Each great house was a coordinate, a landmark on a vast, intricate map that encompassed not just the immediate canyon but extended hundreds of miles across the San Juan Basin. Their orientations are often aligned with cardinal directions, solstices, and equinoxes, transforming architecture into an observatory, a calendar, and a guide.

Consider Pueblo Bonito, the undisputed crown jewel. Its colossal D-shape dominates the canyon floor, a labyrinth of over 600 rooms, numerous kivas (circular ceremonial chambers), and plazas. Walking through its ancient doorways, feeling the cool stone walls, one can almost hear the hum of activity from a millennium ago. But its significance goes beyond its sheer scale. Pueblo Bonito’s northern wall is perfectly aligned with the cardinal directions, and its internal structures mark the sun’s passage at critical times of the year. The entire structure, therefore, functions as a grand, fixed map, indicating the sun’s movements and, by extension, the seasons for planting, harvesting, and ceremony. It was a central node, a civic and ceremonial heart, from which the Chacoan world was understood and organized.

Beyond the Great Houses themselves, the Chacoan "maps" extended through an astonishing network of ancient roads. These meticulously engineered pathways, some up to 30 feet wide and extending for dozens of miles, connected Chaco Canyon to over 150 outlying communities, known as "outliers." These roads weren’t merely utilitarian; they were straight, often ignoring natural topography, suggesting a ceremonial or symbolic purpose. They connected disparate communities, facilitating trade, communication, and the flow of people and ideas, but they also acted as lines on a vast, living map – a network of spiritual arteries linking the Chacoan world. For the traveler today, hiking sections of these ancient roads offers a profound sense of connection to the past, tracing paths walked by countless Ancestral Puebloans. You can feel the intention behind their unwavering straightness, a deliberate connection to distant points that must have held immense significance.

Another critical element of Chacoan mapping is found in its petroglyphs and pictographs. Carved and painted onto canyon walls and boulders, these images are more than just ancient art; many are sophisticated astronomical observations. The most famous example is the "Sun Dagger" site on Fajada Butte. While access to the top of Fajada Butte is now restricted for preservation, its story remains central to understanding Chacoan mapping. Here, three large stone slabs, precisely placed by ancient hands, create light and shadow patterns on a spiral petroglyph. At summer solstice noon, a "dagger" of light pierces the center of the spiral. At winter solstice, two daggers frame the spiral. And at equinoxes, another light pattern bisects it. This site is a calendrical map, a precise marker of the sun’s journey, crucial for an agricultural society. It demonstrates a level of astronomical knowledge and engineering prowess that continues to astound modern researchers and visitors alike.

The night sky itself was arguably the most comprehensive and continuously observed "map" for the Ancestral Puebloans. Chaco Canyon is an International Dark Sky Park, offering some of the clearest, darkest night skies in North America. Imagine standing in the plaza of Pueblo Bonito on a moonless night, the Milky Way a brilliant river overhead, stretching from horizon to horizon. For the Chacoans, this wasn’t just a beautiful spectacle; it was a cosmic atlas, a spiritual guide, and a source of profound knowledge. Constellations, planetary movements, and meteor showers would have been meticulously observed and integrated into their cosmology, informing their architectural alignments and ceremonial practices. Visiting Chaco and experiencing its night sky is to commune with the same celestial map that guided its ancient inhabitants, forging a palpable link across millennia.

For the modern traveler, Chaco Canyon offers an experience unlike any other. It’s a place of profound silence, broken only by the whisper of the wind and the call of birds. This solitude allows for deep introspection and an intimate connection with the past. As you explore the Great Houses, either on foot or by bicycle (rentals available at the visitor center), you’re not just seeing stones; you’re witnessing the remnants of a highly organized, spiritually rich society that thrived in a challenging environment. The scale of their ambition, their communal effort, and their sophisticated understanding of their world are humbling.

A visit typically involves driving the 9-mile loop road that connects the major sites. Start at the Visitor Center to gain context, then proceed to the main attractions. Pueblo Bonito is a must, taking at least an hour or two to explore its intricate layout. Chetro Ketl, with its massive kiva and unique tri-wall structures, offers a different perspective on Chacoan architecture. Kin Kletso showcases influence from Mesa Verde and Aztec Ruins, hinting at wider connections within the Chacoan world. For those seeking more strenuous activity, trails lead to the top of the canyon mesas, offering panoramic views of the entire canyon and the distant outliers. These hikes, such as the South Mesa Trail, allow you to see the Great Houses from above, truly appreciating their placement within the landscape – how they fit into that grand, multi-dimensional map.

Beyond the major sites, the feeling of the place itself is a powerful draw. The remote location, the stark beauty of the desert, and the sheer antiquity of the structures combine to create an atmosphere of profound mystery. Why did they build so grandly? What led to their eventual departure around 1250 CE? These questions linger, adding to the allure. The Ancestral Puebloans left no written language in our modern sense, but their "maps" – their architecture, their roads, their rock art, and their astronomical observations – tell a story far richer than any text could convey. They speak of a people deeply attuned to their environment, who saw the land and the sky as interconnected, sacred entities.

Planning Your Chaco Adventure:

- When to Go: Spring and fall offer the most pleasant temperatures for exploring. Summer can be brutally hot, and winters can be cold with occasional snow, though winter stargazing can be spectacular.

- Getting There: Chaco is remote. Access is primarily via unpaved roads (CR 7900 or CR 7950 from US 550, or NM 57 from NM 371). Check road conditions with the park service before you go, especially after rain or snow. A high-clearance vehicle is recommended, though not strictly necessary in dry conditions.

- What to Bring: Water, water, and more water! There is no potable water available at the park beyond the Visitor Center. Also bring sun protection (hat, sunscreen), layers of clothing (desert temperatures fluctuate wildly), sturdy hiking shoes, and food. There are no services within the park.

- Where to Stay: Camping is available at Gallo Campground within the park, which often fills up. Reservations are highly recommended. Otherwise, the nearest towns with accommodations are Farmington (about 2.5 hours north) or Cuba (about 2 hours east). Many choose to make it a day trip.

- Respect the Site: Chaco is sacred to many Native American communities. Stay on marked trails, do not climb on walls, and leave no trace. Preserve this irreplaceable heritage for future generations.

- Stargazing: If possible, plan an overnight stay. The night sky at Chaco is an experience unto itself, a direct connection to the ancient "maps" that guided the Ancestral Puebloans. Check the park’s schedule for ranger-led night sky programs.

Chaco Canyon is more than a destination; it’s a journey into the profound wisdom of an ancient civilization. It challenges us to reconsider what a "map" truly is, revealing it not as a static diagram but as a dynamic, integrated understanding of the world – a fusion of architecture, astronomy, spirituality, and community. Walking its hallowed grounds, you don’t just see the past; you feel its enduring presence, a testament to the power of human ingenuity and an unbreakable bond with the earth and the cosmos. This is a travel experience that will resonate long after the dust has settled from your boots.