Here is a 1200-word article for a travel blog, directly reviewing Badlands National Park through the lens of 1800s land surveys and Native American maps.

>

The first breath of air in Badlands National Park is a revelation: dry, vast, carrying the scent of ancient dust and resilient prairie grass. The landscape itself is a lesson in erosion, a raw, exposed tapestry of buttes, pinnacles, and spires carved by millennia of wind and water. This isn’t merely a scenic drive; it’s a journey into the very fabric of American history, a place where the stark beauty of the land forces a confrontation with how it was understood, mapped, and ultimately, claimed during the tumultuous 1800s. For a traveler seeking more than just Instagrammable vistas, the Badlands offers a profound entry point into the colliding worlds of early American land surveys and the intricate, deeply spiritual "maps" of its Indigenous inhabitants.

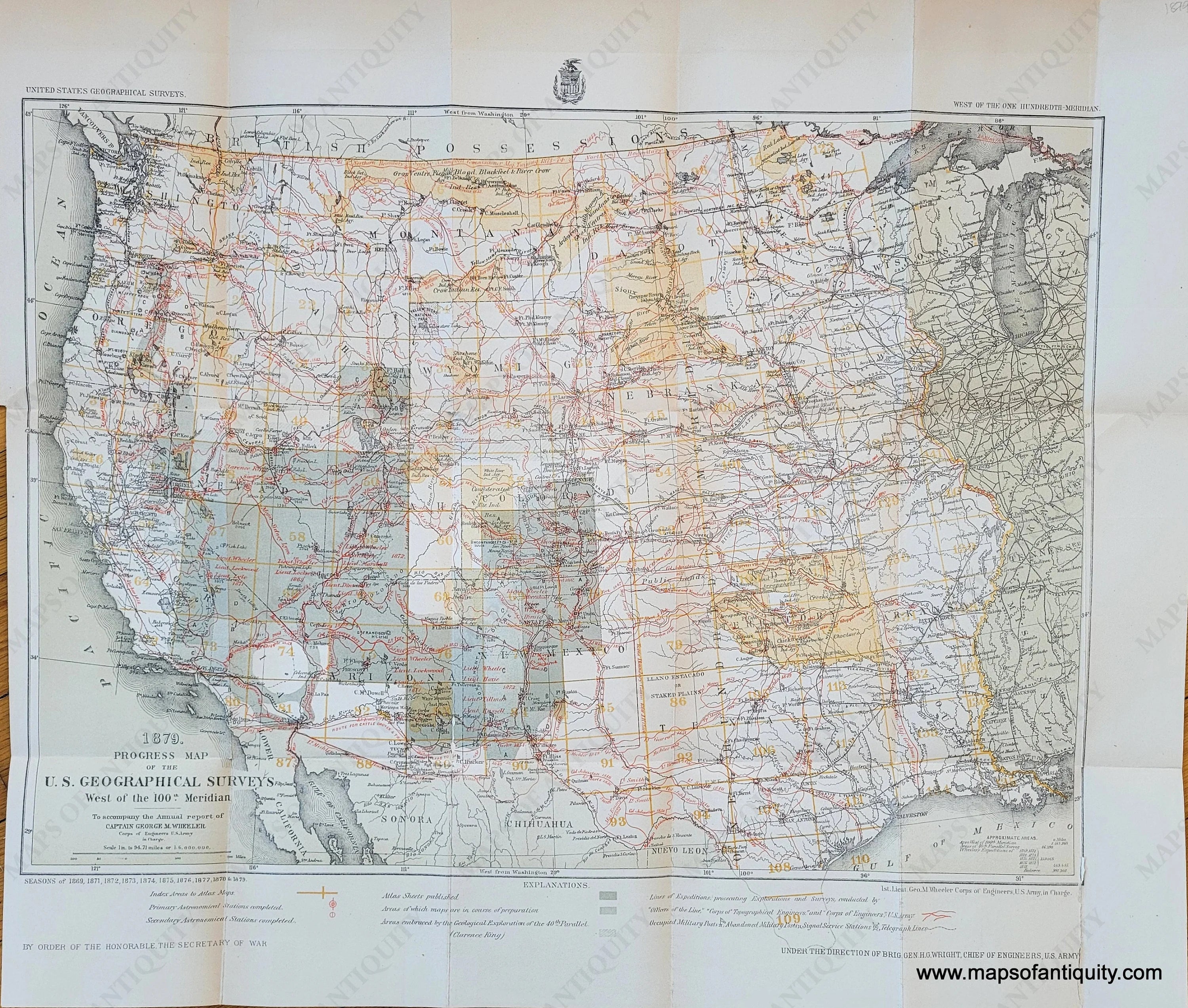

Driving the Badlands Loop Scenic Byway, the undulating terrain seems to defy any notion of a straight line. Yet, it was precisely the imposition of straight lines – the relentless, methodical grid of the General Land Office (GLO) surveys – that fundamentally reshaped this continent. Imagine the surveyors of the 1800s, often ex-soldiers or hardy frontiersmen, standing on a ridge much like the one overlooking the Pinnacles Overlook. Their instruments – transits, chains, magnetic compasses – were crude by modern standards, yet they were tasked with carving an abstract geometric order onto a chaotic, untamed wilderness. They were the vanguards of manifest destiny, laying down the invisible meridians and base lines that would define townships, sections, and eventually, private property.

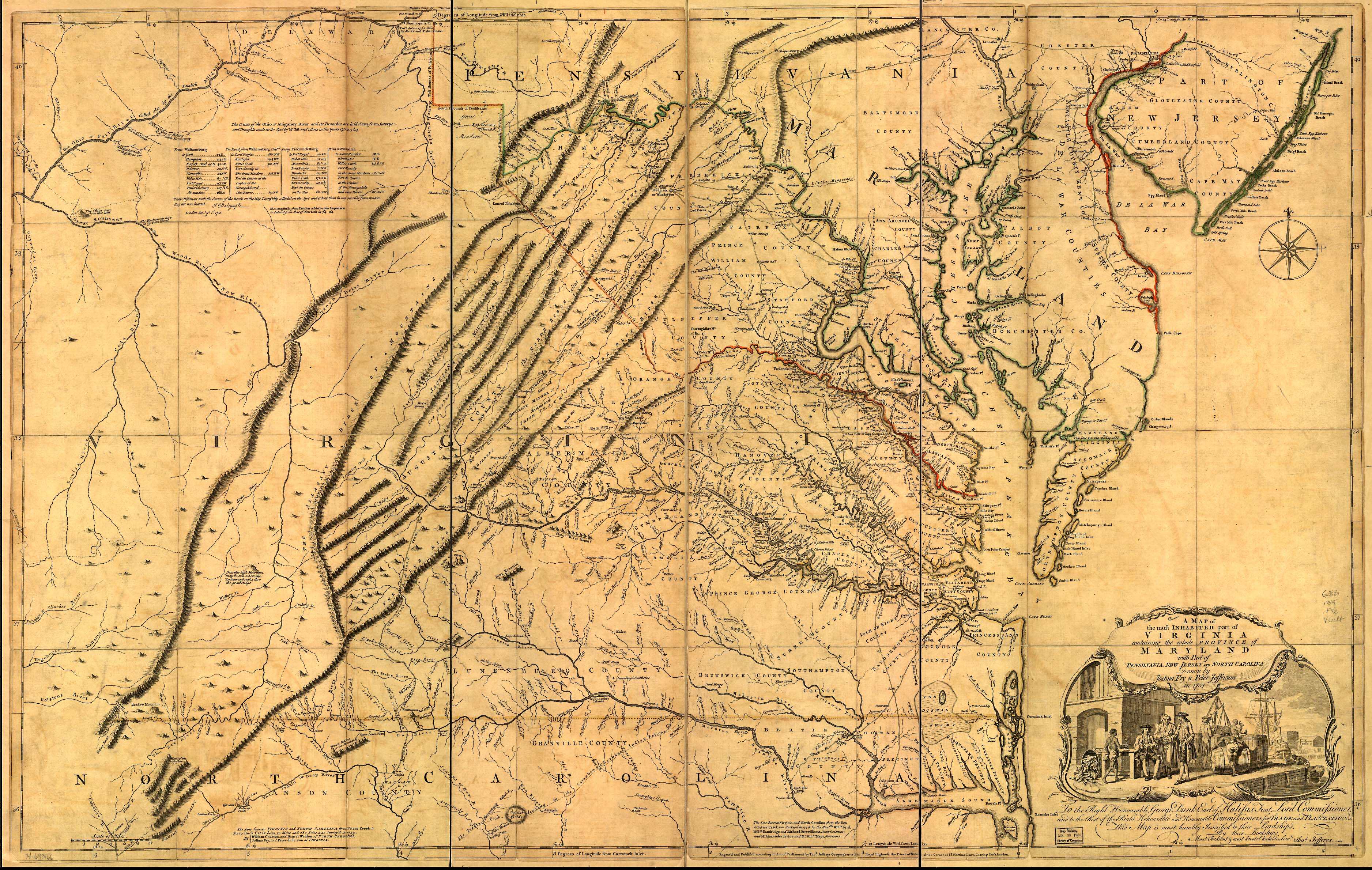

The challenges they faced here in the Badlands would have been immense. This isn’t fertile farmland; it’s a geological wonderland, treacherous to traverse, prone to sudden weather shifts, and teeming with wildlife that could be both a resource and a threat. Every rise and fall, every impassable gully, every sudden drop-off into a chasm had to be accounted for, measured, and recorded. Their maps, meticulously drawn on vellum or linen, were not artistic interpretations but cold, hard data: bearings, distances, and descriptions of "witness trees" or other natural markers that would delineate boundaries. These maps were the legal blueprints for an expanding nation, the foundation upon which land patents would be issued, railroads built, and settlements established.

But these GLO maps, for all their precision in geometric terms, were profoundly ignorant of the landscape’s true meaning. They were a colonial imposition, a foreign language spoken over the ancient narratives of the Lakota and other Indigenous peoples who had called this land home for generations. Their maps were not drawn on paper with lines and numbers; they were etched into memory, passed down through oral tradition, embodied in sacred stories, and reflected in the intimate knowledge of seasonal cycles, water sources, game trails, and sacred sites.

Consider the Lakota understanding of the Badlands, or Mako Sica – "bad lands" – a name that speaks less to its navigability and more to its stark beauty, its spiritual power, and its role as a refuge and hunting ground. Their maps were fluid, relational, and ecological. A "map" might be a story of a vision quest taken on a particular butte, or a detailed understanding of where bison herds grazed in spring versus winter, or the location of specific medicinal plants. The rivers, like the White River that skirts the northern edge of the park, weren’t just lines on a grid; they were lifelines, arteries of connection, sources of sustenance. The Black Hills, visible on a clear day to the west, were not just another mountain range but Paha Sapa, the sacred heart of their world, a place of profound spiritual significance.

The clash between these two mapping ideologies – the Euclidean grid versus the ecological and spiritual web – lies at the heart of the dispossession of Indigenous lands. The Fort Laramie Treaties of 1851 and 1868, for instance, attempted to define vast tracts of land as "Great Sioux Reservation," using the very boundary lines that GLO surveyors would eventually demarcate. Yet, even these treaties, signed under duress and often violated, failed to capture the true Indigenous understanding of territory, which encompassed not just exclusive ownership but also communal use, access to vital resources across broad landscapes, and the spiritual interconnectedness of all things. When gold was discovered in the Black Hills, a region supposedly protected by treaty, the lines on the GLO maps meant nothing to the gold-hungry prospectors, nor to the U.S. government that soon moved to seize the land, leading to the devastating Great Sioux War.

Today, as you hike the Door Trail or the Notch Trail in the Badlands, scrambling over ladders and navigating narrow passages, you can almost feel the presence of those early surveyors, battling the terrain with their chains and transits. You can also imagine the Lakota hunting parties, moving silently and efficiently through this same landscape, guided by an internal map far more sophisticated for survival than any paper chart. The fossil beds, exposed by erosion, reveal not just ancient life but also the layers of time that shaped the land, a deep history that Indigenous narratives have always honored.

The Ben Reifel Visitor Center provides excellent interpretive exhibits, and often includes historical maps – both GLO surveys and attempts to represent Indigenous territories. Studying these side-by-side offers a powerful visual metaphor for the cultural collision. One sees the land as an empty canvas for ownership; the other sees it as a living entity, already named, already known, already sacred.

Even the park’s modern boundaries, though drawn with contemporary surveying techniques, echo this historical tension. Badlands National Park is surrounded by the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, home to the Oglala Lakota. This proximity is not accidental; it is a direct legacy of those 1800s land surveys and the treaties that confined Indigenous peoples to ever-shrinking parcels of their ancestral lands. Traveling through the park, and perhaps extending your journey to the reservation, offers a tangible connection to this ongoing historical narrative. It prompts reflection on the enduring resilience of Native cultures and their continued stewardship of the land.

Visiting Badlands National Park isn’t just about witnessing geological wonders; it’s an opportunity to engage with a pivotal chapter in American history written on the very landscape. It’s about understanding how the land was seen, how it was mapped, and how those different ways of seeing led to profound and lasting consequences. By consciously seeking out the echoes of 19th-century land surveys and the deep, rich tapestry of Native American maps – both physical and conceptual – your trip transforms from a simple scenic tour into a powerful, thought-provoking exploration of identity, ownership, and the enduring spirit of place. It’s a reminder that every line on a map tells a story, and often, many conflicting ones. To truly appreciate the Badlands, you must attempt to read them all.