Here’s an article for a travel blog, reviewing a location deeply connected to the Native American linguistic groups map, written in English and directly addressing the topic without preamble.

>

Decoding the Continent: A Deep Dive into Native American Linguistic Tapestries at the National Museum of the American Indian

For the avid traveler, maps are more than mere navigation tools; they are invitations to discovery, stories etched in lines and colors. But few maps possess the profound, living narrative of the Native American linguistic groups map. It’s a cartographic marvel that doesn’t just delineate borders but echoes millennia of human ingenuity, adaptation, and profound connection to land. To truly grasp the weight and wonder of this map, one must move beyond the two-dimensional representation and step into a space where these ancient voices resonate. My journey took me to the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., a place that doesn’t just display artifacts, but actively breathes life into the complex, beautiful, and often challenging story of Indigenous languages across the Americas.

Forget the conventional notion of a museum as a dusty repository of the past. The NMAI, with its distinctive curvilinear architecture of Kasota limestone, evokes natural geological formations – a deliberate choice reflecting Native American respect for the earth. Its setting on the National Mall is significant; it positions Indigenous voices at the very heart of the nation’s capital, a powerful statement in itself. My review isn’t just about the building or its collections, but how it functions as an unparalleled gateway to understanding the incredible linguistic diversity that predates and permeates the North American continent.

Bringing the Linguistic Map to Life: Beyond the Static Image

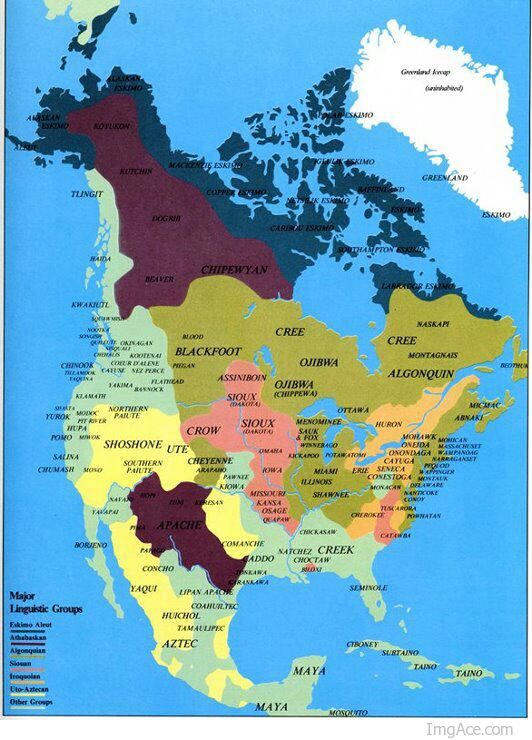

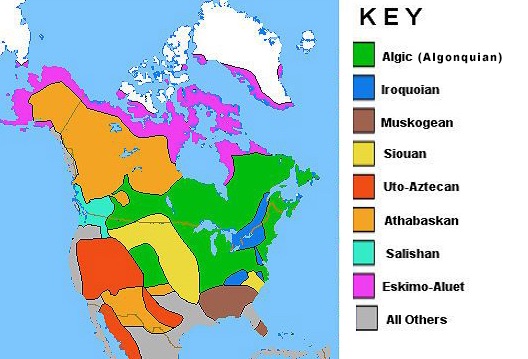

The linguistic map of Native North America is a breathtaking mosaic. It’s not just a handful of languages, but hundreds, grouped into dozens of distinct families – Algic, Iroquoian, Siouan, Uto-Aztecan, Athabaskan, Salishan, Eskimo-Aleut, and countless isolates. Each family represents an ancient tree of knowledge, with its own unique phonology, grammar, and worldview. Seeing this map on a screen or in a textbook is one thing; experiencing it through the NMAI’s curated narratives is another entirely.

The museum’s approach is fundamentally different from many colonial-era institutions. It’s built on a foundation of consultation and collaboration with Native communities, ensuring that the stories are told by and through Indigenous perspectives. This is crucial when dealing with something as sensitive and integral as language. You won’t find sweeping, generalized statements here. Instead, you encounter specific voices, specific tribes, and specific linguistic traditions, allowing you to trace the contours of that map with tangible examples.

One of the most impactful ways the NMAI illuminates linguistic diversity is through its strategic use of multimedia. Throughout the permanent exhibitions like "Our Universes: Traditional Knowledge Shapes Our World" and "Our Peoples: Giving Voice to Our Histories," visitors encounter audio and video installations that feature Native speakers. Hearing the guttural clicks of a Salishan language, the melodic tones of an Iroquoian tongue, or the complex inflections of Navajo (Diné Bizaad) transforms abstract linguistic categories into vibrant, living sounds. It’s an auditory journey that literally gives voice to the map. You begin to grasp that these aren’t just "different words" but fundamentally different ways of perceiving and structuring reality. The very syntax often reflects different cultural priorities and relationships to the environment.

A Journey Through Linguistic Families (and Their Challenges)

The museum doesn’t shy away from the challenges faced by Indigenous languages – the devastating impact of colonization, forced assimilation, and the ongoing struggle for revitalization. Yet, it frames these not as tales of defeat, but as testaments to resilience and ongoing efforts.

As you wander through the exhibits, you implicitly trace the major linguistic families:

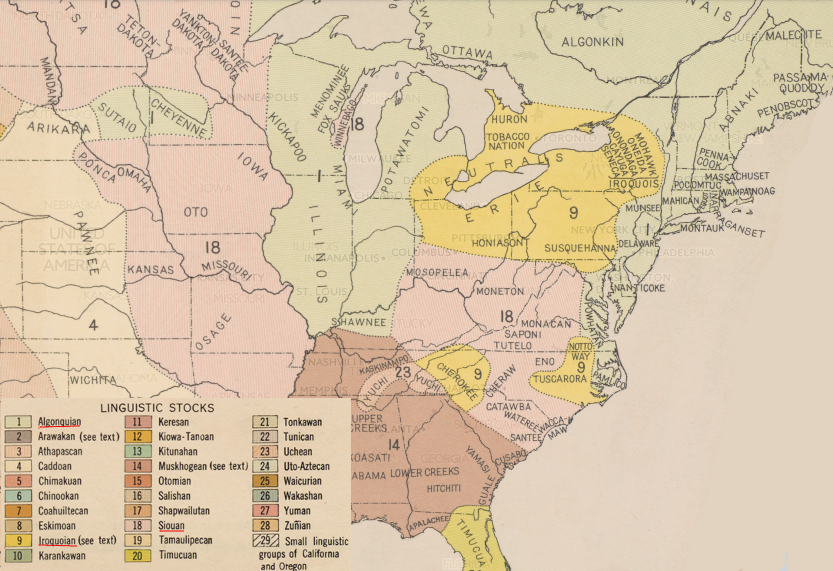

- The Northeast and Great Lakes: Here, the legacies of Algonquian languages (like Ojibwe, Cree, Blackfoot, Cheyenne) and Iroquoian languages (Mohawk, Seneca, Cherokee) are powerfully represented. Exhibits on wampum belts, governance, and agricultural practices often include explanations of their linguistic origins and how language carries cultural protocols and historical memory. You learn how words are not just labels but contain entire philosophies.

- The Southeast: While many languages here, like those of the Timucua or Natchez, are tragically lost, the enduring spirit of the Muskogean family (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek) and the transplanted Cherokee (an Iroquoian language) are highlighted. The story of Sequoyah and the Cherokee syllabary is a powerful testament to linguistic innovation and self-determination, a vital counter-narrative to the idea of "primitive" languages.

- The Plains: The vast prairies were home to a mosaic of Siouan (Lakota, Dakota, Omaha), Caddoan (Pawnee, Wichita), and Algonquian (Arapaho, Cheyenne) speakers. Displays of regalia, tipis, and ceremonial objects are accompanied by the stories and songs that define these cultures, often in their original languages, underscoring how language, song, and dance are inextricably linked.

- The Southwest: This region is a linguistic hotspot, featuring the ancient Keresan and Zuni isolates, the widely distributed Uto-Aztecan family (Hopi, Ute, Shoshone), and the relatively recent but expansive Athabaskan migration (Navajo/Diné, Apache). The NMAI showcases the profound spiritual and agricultural traditions of the Pueblo peoples and the intricate weaving and philosophical depth of the Navajo, all deeply embedded in their respective languages. Hearing Hopi ceremonial songs or Navajo blessings is a direct connection to a worldview shaped by these distinct linguistic frameworks.

- The Northwest Coast: Here, a dense cluster of unrelated language families – Salishan, Wakashan, Tsimshian, Haida – developed sophisticated societies with rich oral traditions, intricate art (like totem poles), and complex social structures. The museum’s focus on clan systems, potlatches, and spirit canoes implicitly highlights how language encoded these elaborate cultural systems.

- The Arctic and Subarctic: The languages of the Eskimo-Aleut family (Inuit, Yupik) and various Athabaskan groups (Gwich’in, Dene) are represented through the ingenious technologies and survival strategies developed for harsh environments. The precision of their vocabulary for snow, ice, and animal life speaks volumes about their deep ecological knowledge, a testament to how environment shapes language and vice versa.

More Than Words: The Cultural Context of Language

What makes the NMAI so effective is its refusal to isolate language from its cultural context. You don’t just learn about a language; you learn why it matters to its speakers. Through exhibits on traditional foods, you might learn Indigenous names for plants and animals, understanding the intimate relationship between language and subsistence. The Mitsitam Cafe, the museum’s exceptional restaurant, offers Indigenous-inspired cuisine from different regions, further immersing visitors in the tastes and traditions connected to these diverse linguistic groups. Eating a dish inspired by the Northwest Coast while contemplating the intricacies of a Salishan language creates a holistic, sensory experience of Indigenous culture.

Art, too, is presented as a form of communication, often carrying narratives and symbols that are deeply intertwined with oral traditions and specific linguistic concepts. Contemporary Native artists use their work to explore identity, history, and the future of their languages, demonstrating that Indigenous cultures are not static but dynamic and evolving. The museum frequently hosts living cultural demonstrations, performances, and talks by Native scholars and artists, providing direct interaction and the opportunity to hear Indigenous languages spoken in real-time. These events are where the "map" truly becomes alive, not as historical data, but as a vibrant, ongoing legacy.

A Call to Action and Deeper Understanding

Visiting the NMAI is not just a passive educational experience; it’s an invitation to engage. It encourages visitors to think critically about the politics of language, the power of oral traditions, and the vital importance of language revitalization efforts. The museum subtly yet powerfully conveys that the loss of a language is not just the loss of words, but the loss of unique knowledge systems, worldviews, and cultural heritage. Conversely, the resilience and ongoing efforts to preserve and teach Indigenous languages represent a profound act of self-determination and cultural strength.

For anyone fascinated by the sheer diversity of human expression, by the intricate relationship between language and culture, or simply by the rich history of the North American continent, the National Museum of the American Indian is an indispensable destination. It transforms the abstract lines of a linguistic map into a symphony of voices, stories, and living traditions. It is a place that challenges preconceptions, inspires awe, and leaves you with a profound appreciation for the enduring power and beauty of Indigenous languages – a journey that truly decodes the continent.

>