>

Unfolding the Living Map: A Journey Through Michigan’s Native American Heritage

Maps are more than mere geographical outlines; they are palimpsests, layers of history, identity, and untold stories. For Michigan, a state defined by its majestic Great Lakes, understanding its Native American tribal map is not just an academic exercise – it’s an essential journey into the heart of its land, its people, and its enduring spirit. This isn’t a static map of lines drawn by colonial powers, but a dynamic, living testament to millennia of indigenous presence, resilience, and cultural richness.

To truly grasp Michigan’s Native American heritage, we must move beyond the conventional and explore the deep historical roots and contemporary vibrancy of its first peoples. This article will unfold the layers of Michigan’s indigenous map, revealing the intricate tapestry of its tribes, their historical territories, their identities forged through time, and their powerful modern-day presence.

The Anishinaabe Nations: The Heartbeat of Michigan

At the core of Michigan’s indigenous landscape are the Anishinaabe peoples, often referred to as the "Three Fires Confederacy": the Ojibwe (Chippewa), Odawa (Ottawa), and Potawatomi. Bound by common language (Algonquian), cultural practices, and a profound sense of shared destiny, these nations have called the Great Lakes region home for centuries, shaping its environment and being shaped by it.

The Ojibwe (Anishinaabemowin: Anishinaabeg): The Keepers of the Faith

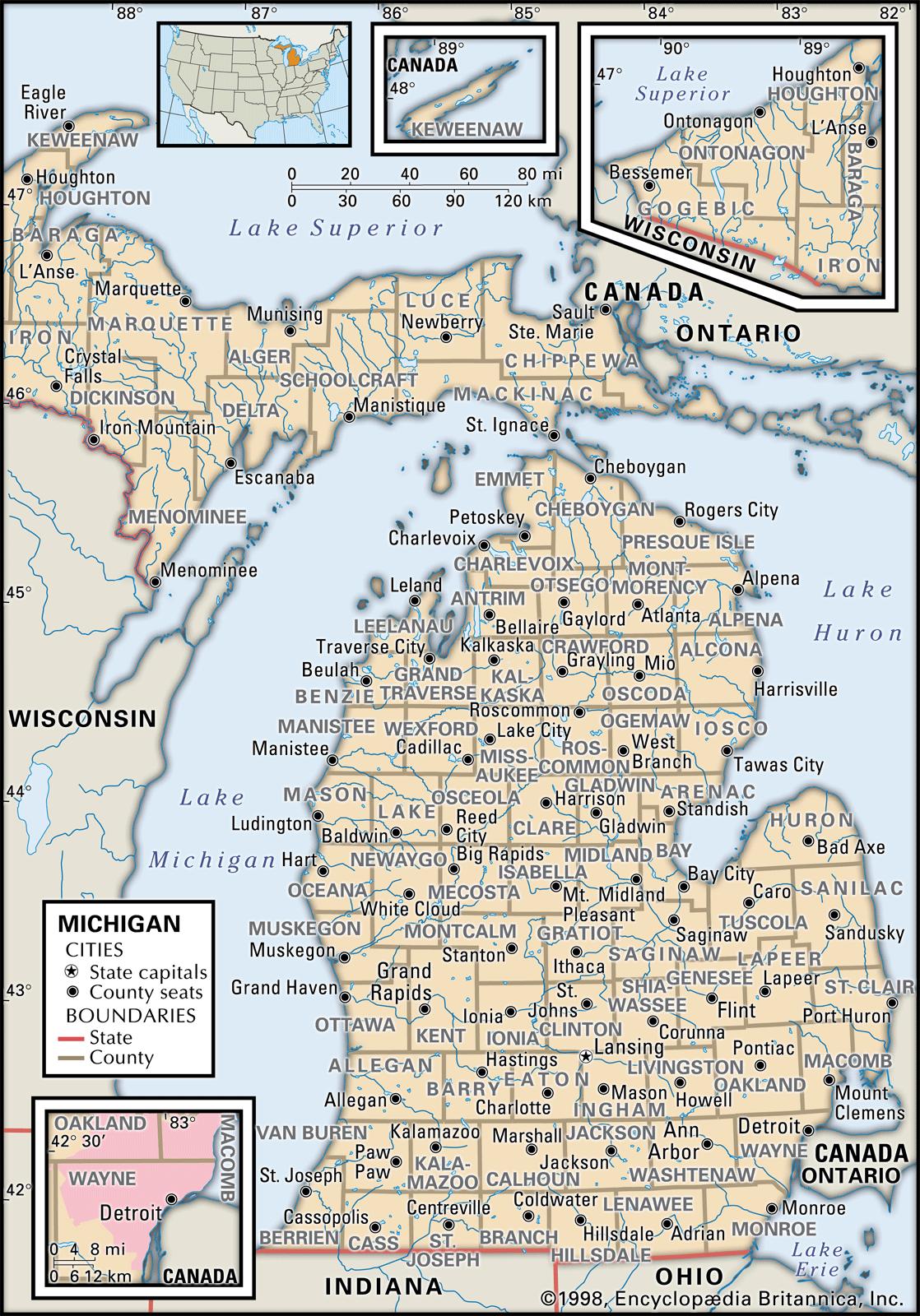

The Ojibwe, or Chippewa as they are often known, are the most populous and widespread of the Anishinaabe nations, their traditional territories stretching across the Upper Peninsula and northern Lower Peninsula of Michigan, and far beyond into Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Canada. Their name, often translated as "puckered moccasin," speaks to their craftsmanship. The Ojibwe were renowned for their sophisticated use of birchbark for canoes, containers, and even scrolls for recording sacred knowledge. They were masterful hunters, fishers, and gatherers, utilizing the abundant resources of the Great Lakes – particularly wild rice (manoomin), which was a staple and a spiritual gift. Their identity is deeply tied to the land’s spiritual power and the intricate ceremonial life, including the Midewiwin, or Grand Medicine Society, which preserves ancient teachings and healing practices.

The Odawa (Anishinaabemowin: Odaawaa): The Traders and Navigators

The Odawa, whose name means "traders" or "those who trade," were strategically positioned along the vital waterways of the Great Lakes, particularly around the northern Lower Peninsula and its surrounding islands, such as Mackinac Island. Their identity was intrinsically linked to their role as skilled navigators and merchants, facilitating trade networks that stretched for hundreds of miles, exchanging furs, corn, tobacco, and other goods. Their mastery of canoe travel and their extensive knowledge of the region’s geography made them indispensable partners and formidable independent actors in the early contact period with European explorers. The Odawa were also known for their agricultural prowess, cultivating corn, beans, and squash, which complemented their hunting and fishing activities.

The Potawatomi (Anishinaabemowin: Bodéwadmi): The Keepers of the Fire

The Potawatomi, meaning "Keepers of the Fire," traditionally inhabited the southern Lower Peninsula of Michigan, extending into parts of Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Their name signifies their role in maintaining the sacred fire of the Three Fires Confederacy, symbolizing their spiritual and political connection. The Potawatomi were primarily agriculturalists, growing extensive fields of corn, beans, and squash, alongside hunting and gathering. Their identity is often associated with their remarkable resilience and adaptability, particularly in the face of immense pressure and forced removals during the 19th century. Despite significant displacements, communities in Michigan and elsewhere fiercely maintained their cultural identity, language, and ceremonial practices.

Beyond the Three Fires: Other Historical Presences

While the Anishinaabe nations form the bedrock of Michigan’s indigenous history, it’s important to acknowledge other groups whose historical territories or influences touched the region. The Menominee people, whose name means "Wild Rice People," historically occupied lands along Michigan’s western Upper Peninsula border with Wisconsin, reflecting their profound connection to the staple grain. Their presence, though primarily associated with Wisconsin, extended into the rich resource areas of Michigan’s westernmost regions.

Further east, the Wyandot (Huron), though primarily located in Ohio and southern Ontario, had significant interactions and historical ties with the Anishinaabe nations, particularly in the early colonial period. Their displacement and alliances often rippled through the Great Lakes region, influencing tribal maps and political landscapes.

The Pre-Colonial Map: A Fluid Tapestry of Life

Before European contact, the "map" of Michigan’s Native American tribes was not defined by rigid, colonial-style borders. Instead, it was a fluid tapestry of seasonal movements, resource-based territories, and kinship networks. Tribes utilized vast areas for hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture, often sharing hunting grounds or having overlapping claims that were managed through complex diplomatic protocols and occasional conflicts.

The Great Lakes themselves were not boundaries but highways, facilitating trade, communication, and cultural exchange. Rivers and trails crisscrossed the land, connecting communities and defining pathways of life. This pre-colonial map was a living entity, reflecting the deep ecological knowledge and sustainable practices of its peoples, who understood the land as a relative, not merely a resource to be exploited. Their settlements shifted with the seasons, following game, fish runs, and ripening berries, embodying a profound connection to the natural cycles of their environment.

The Colonial Impact: Redrawing the Map with Treaties and Displacement

The arrival of European powers – first the French, then the British, and finally the Americans – dramatically and tragically reshaped Michigan’s indigenous map. The fur trade initially forged alliances, but eventually led to competition, disease, and the erosion of indigenous sovereignty.

The 19th century marked a brutal era of treaty-making. Under immense pressure, and often through coercion and deception, Michigan’s Native American nations were forced to cede vast tracts of their ancestral lands to the United States government. Treaties such as the Treaty of Detroit (1807), Treaty of Saginaw (1819), Treaty of Chicago (1821), and the Treaty of Washington (1836) systematically carved up Michigan, leaving only small, fragmented parcels of land – the beginnings of what would become reservations.

This period of forced removal and land cession fundamentally altered the indigenous map. Traditional territories were dismembered, communities were displaced, and the intricate web of intertribal relationships was severely strained. The map became one of shrinking enclaves, isolated communities, and a desperate struggle for survival against overwhelming odds. Many Potawatomi were forcibly removed to lands west of the Mississippi, a journey known as the "Potawatomi Trail of Death," though some managed to resist removal and remain in Michigan.

The Modern Map: Resilience, Reassertion, and Sovereignty

Despite centuries of colonization, forced removals, and attempts at cultural assimilation, Michigan’s Native American nations have demonstrated extraordinary resilience. Today, the modern map of Michigan’s indigenous presence is a testament to their enduring sovereignty, cultural revitalization, and self-determination.

Michigan is home to 12 federally recognized Native American tribes, each with its own sovereign government, distinct identity, and vibrant community. These tribes are:

- Bay Mills Indian Community (Ojibwe)

- Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians (Odawa, Ojibwe)

- Hannahville Indian Community (Potawatomi)

- Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (Ojibwe, L’Anse and Lac Vieux Desert Bands)

- Lac Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians (Ojibwe)

- Little River Band of Ottawa Indians (Odawa)

- Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians (Odawa)

- Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians of Michigan (Gun Lake Tribe) (Potawatomi)

- Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi (Potawatomi)

- Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians (Potawatomi)

- Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi)

- Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians (Ojibwe)

These tribes represent the living map of Michigan’s indigenous heritage. Their lands, often referred to as reservations or trust lands, are sovereign territories where tribal laws and governance prevail. The map today shows pockets of vibrant self-governance, economic development (including casinos, resorts, and other enterprises that fund essential tribal services), and robust efforts in cultural preservation, language revitalization, and historical education.

For travelers and history enthusiasts, understanding this modern map is crucial. It signifies not just historical sites but living communities. Tribal cultural centers, museums, and annual powwows offer invaluable opportunities to learn directly from the source, to experience Anishinaabe culture, and to appreciate the ongoing contributions of Michigan’s first peoples.

Understanding the Map for Travelers and Learners

For those traveling through Michigan, particularly for education and appreciation of history, the indigenous map offers profound insights:

- Beyond the Stereotype: Move past outdated images and engage with the contemporary reality of sovereign nations.

- Acknowledge the Land: Recognize that every part of Michigan is ancestral land. Understanding whose traditional territory you are on deepens your connection to the place.

- Visit Tribal Cultural Centers: Many tribes operate museums and cultural centers that provide authentic historical narratives and showcase contemporary art, language, and traditions. These include the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabek Culture and Lifeways (Saginaw Chippewa), the Eyaawing Museum & Cultural Center (Grand Traverse Band), and the Pokagon Band’s cultural offerings.

- Attend Public Events: Public powwows are celebrations of culture, dance, and community. Attend with respect, follow etiquette, and embrace the opportunity to learn.

- Support Tribal Economies: Patronizing tribal businesses, from resorts to gas stations, directly supports tribal governments and services.

- Learn the Language: Even learning a few words of Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi) can be a powerful gesture of respect.

Conclusion: A Living Legacy

The map of Michigan’s Native American tribes is not a static artifact of the past, but a vibrant, evolving narrative. It tells a story of deep connection to the land, of profound cultural identity, of devastating loss, and of incredible resilience. From the ancient pathways of the Anishinaabe Confederacy to the sovereign territories of today’s federally recognized tribes, this map invites us to see Michigan not just as a state on a modern atlas, but as a homeland with thousands of years of human history embedded in its very soil and waters.

By exploring this living map, we honor the legacy of Michigan’s first peoples, gain a deeper understanding of its history, and commit to a future of respect, recognition, and collaboration. It is an invitation to look beyond the lines and discover the heart of Michigan.

>