Mapping the Heart of the Plains: A Traveler’s Guide to Indigenous Cartography at the Buffalo Bill Center

Forget everything you think you know about maps. For centuries before European contact, and long after, the Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains navigated, understood, and depicted their world not with grid lines and compass roses, but with stories, memory, and an intimate connection to the land itself. Their maps were living documents, etched onto hides, painted on rocks, woven into narratives, and memorized through generations. To truly grasp the vastness and cultural depth of the Great Plains, one must learn to read these original maps – and there’s no better place to begin this transformative journey than the Plains Indian Museum, a cornerstone of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

Nestled on the eastern edge of the Yellowstone ecosystem, Cody might seem an unlikely epicenter for such an exploration, yet the Buffalo Bill Center is a world-class institution dedicated to preserving and interpreting the diverse histories of the American West. Within its five museums, the Plains Indian Museum stands as a vibrant tribute to the art, history, and enduring spirit of the Native peoples who called this immense landscape home. It’s here that the concept of Indigenous cartography, often relegated to academic texts, springs to life, offering travelers a profound opportunity to see the world through a different lens.

Beyond Lines and Grids: The Living Maps of the Plains

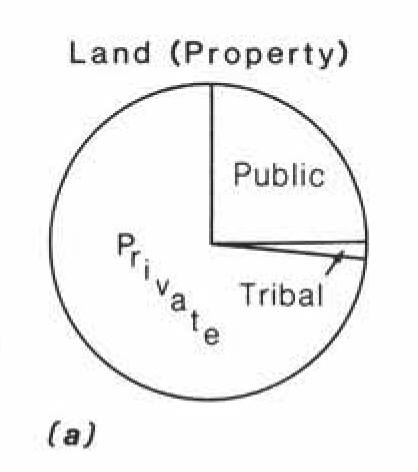

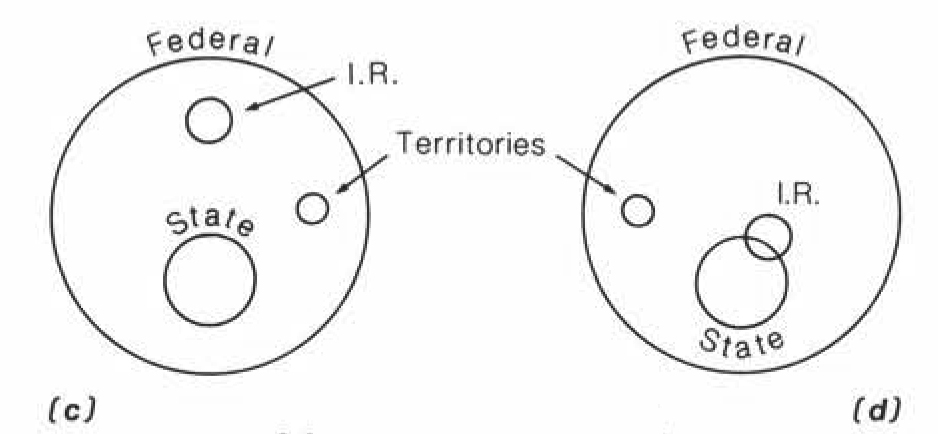

Western cartography, with its emphasis on fixed points, cardinal directions, and quantifiable distances, aims to create a universal, objective representation of space. Indigenous cartography, particularly among the nomadic and semi-nomadic nations of the Great Plains – the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, Blackfeet, Arapaho, Comanche, and many others – operated on fundamentally different principles. Their maps were subjective, contextual, and deeply integrated with their spiritual beliefs, social structures, and practical needs for survival.

These were not maps for detached navigation, but for experiential understanding. They conveyed not just where a river flowed or a mountain stood, but what happened there: a successful buffalo hunt, a significant battle, a sacred ceremony, a seasonal camp. They were repositories of ecological knowledge, guiding people to vital resources like water sources, medicinal plants, and migration routes of game animals. For a travel blogger seeking authentic experiences, understanding this distinction is crucial; it redefines the very act of travel from merely seeing places to understanding them through the eyes of those who have lived there for millennia.

The Plains Indian Museum: A Portal to Indigenous Worlds

Stepping into the Plains Indian Museum is an immersive experience. The air hums with a quiet reverence, and the exhibits are thoughtfully curated, featuring stunning examples of regalia, weapons, tools, and art. While you won’t find a dedicated "cartography wing," the principles of Indigenous mapping are woven throughout the museum’s narrative, inviting visitors to piece together this understanding through various artifacts and interpretive displays.

One of the most compelling forms of Indigenous cartography on display, or represented through historical context, is the hide map. Imagine a tanned buffalo or deer hide, stretched taut, becoming a canvas for the landscape. These were the ultimate portable maps for a mobile people. They depicted migration routes, hunting grounds, and tribal territories, often illustrating significant landmarks with pictographs – a distinct rock formation, a grove of trees, a river bend. The contours of the hide itself could sometimes mimic the rolling plains or the curve of a river.

For instance, you might encounter interpretations of Mandan or Hidatsa village maps, often drawn on animal hides, illustrating the layout of their earthlodge communities along the Missouri River, showing agricultural fields, defensive palisades, and ceremonial spaces. These weren’t just architectural blueprints; they were social diagrams, reflecting kinship structures and spiritual connections to the land. The museum’s extensive collection, even if not every piece is a literal "map," provides the cultural context to understand how these societies would have interpreted their environment. You see the tools, the clothing, the art, and you begin to visualize the people who created these maps, their daily lives intimately tied to the land they depicted.

Stories Carved in Landscape: The Power of Oral Tradition

Beyond physical artifacts, Indigenous cartography is deeply embedded in oral tradition. Place names are not arbitrary labels but mnemonic devices, telling stories of creation, migration, and historical events. A mountain might be named "Where the Bear Stands Tall" because of a significant encounter, or a river "Whispering Waters" due to a particular sound. These names, passed down through generations, function as an intricate navigational system, guiding travelers not just by direction but by narrative.

The museum’s exhibits, through detailed text panels and multimedia presentations, often highlight the importance of these oral histories. As you walk through displays of traditional dwellings or spiritual artifacts, consider how every object, every story, every sacred site contributes to a vast, invisible map. The landscape itself becomes a living text, its features serving as markers in a grand narrative that extends back to time immemorial. For the modern traveler, this encourages a slower, more deliberate exploration, urging us to listen not just to museum audio guides, but to the whispers of history embedded in the very ground we walk upon.

From Hides to Ledgers: Adapting to a Changing World

The arrival of Euro-Americans brought profound changes to the Great Plains, including new materials and new pressures. Indigenous cartographic traditions, however, proved remarkably resilient and adaptable. With the advent of paper, pencils, and ink, particularly after tribes were confined to reservations, a new art form emerged: ledger art. These drawings, often made in old accounting ledgers, continued the tradition of pictorial storytelling, but with new subjects and sometimes new perspectives.

While many ledger drawings depict battles, ceremonies, and daily life, some also contain cartographic elements. They might show the layout of a reservation, the routes of buffalo hunts now confined to smaller areas, or even the new boundaries imposed by treaties. These pieces, often displayed in the Plains Indian Museum, are powerful testaments to the continuity of Indigenous knowledge systems, demonstrating how mapping continued even as the physical landscape and political realities shifted dramatically. They offer a poignant glimpse into a time of transition, where ancient ways of understanding space met new impositions, yet found ways to persist and evolve.

The Traveler’s Perspective: Redefining Exploration

For the discerning traveler, a visit to the Plains Indian Museum isn’t just about viewing historical artifacts; it’s an opportunity for a paradigm shift. It challenges the inherent biases in our own understanding of geography and history. As you wander through the exhibits, consider:

- How would you map your own life if you didn’t use a grid? What stories would define your journeys?

- What vital information would you include for future generations? Beyond simple directions, what spiritual or ecological knowledge would you impart?

- How does understanding Indigenous cartography change your perception of the vast Great Plains? Does it transform from an empty space into a landscape rich with meaning and history?

The museum encourages this kind of thoughtful engagement. It’s a place to slow down, to listen, and to learn. You’ll leave not just with a collection of facts, but with a deeper appreciation for the complex, nuanced ways in which people have always understood and represented their world.

Conclusion: A New Map for Your Journey

The Indigenous cartography of the Great Plains is a testament to human ingenuity, cultural depth, and an profound connection to the land. It reminds us that maps are never truly objective; they are reflections of the cultures that create them, imbued with their values, beliefs, and priorities. The Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West provides an unparalleled gateway to this understanding.

So, when you plan your next adventure to the American West, consider Cody, Wyoming, not just for its proximity to Yellowstone, but as a crucial stop on a different kind of map. Here, you’ll discover that the Great Plains were never truly "unmapped." They were, and remain, a landscape woven with intricate stories, memories, and wisdom, waiting for those willing to learn how to read their original, living maps. Your journey through the Plains Indian Museum will not only enrich your understanding of this incredible region but may just redefine how you look at every map you encounter thereafter.