The San Antonio River, a verdant ribbon weaving through the heart of South Texas, is most often celebrated for its iconic Spanish missions, the Alamo, and the vibrant River Walk. Yet, beneath these familiar layers of history lies an even deeper, more profound narrative: the story of the Indigenous peoples who lived along its banks for millennia, long before any European set foot on this soil. Their history, identity, and enduring legacy are inextricably linked to this river, transforming it from a mere geographical feature into a living historical artery. This article delves into the rich, complex tapestry of Native American tribes near the San Antonio River, offering an educational journey suitable for both the curious traveler and the dedicated history enthusiast.

The Ancient Landscape: A Lifeline of Indigenous Existence

Before the arrival of Europeans, the San Antonio River valley was a thriving ecosystem, a true oasis in the semi-arid landscape of South Texas. Its consistent flow provided fresh water, nurtured diverse plant life, and attracted an abundance of game – deer, bison, rabbits, and a variety of fowl. This richness made the river an ideal home for numerous Indigenous groups, primarily hunter-gatherers, whose lives revolved around its rhythms and resources.

These early inhabitants were not a monolithic entity but a constellation of distinct bands and tribal groups, each with their own language, customs, and territories, though often sharing similar adaptive strategies to the environment. Their existence was characterized by a deep understanding of the land, seasonal migrations for hunting and foraging, and sophisticated social structures that ensured their survival and cultural continuity.

The Coahuiltecan World: An Umbrella of Identities

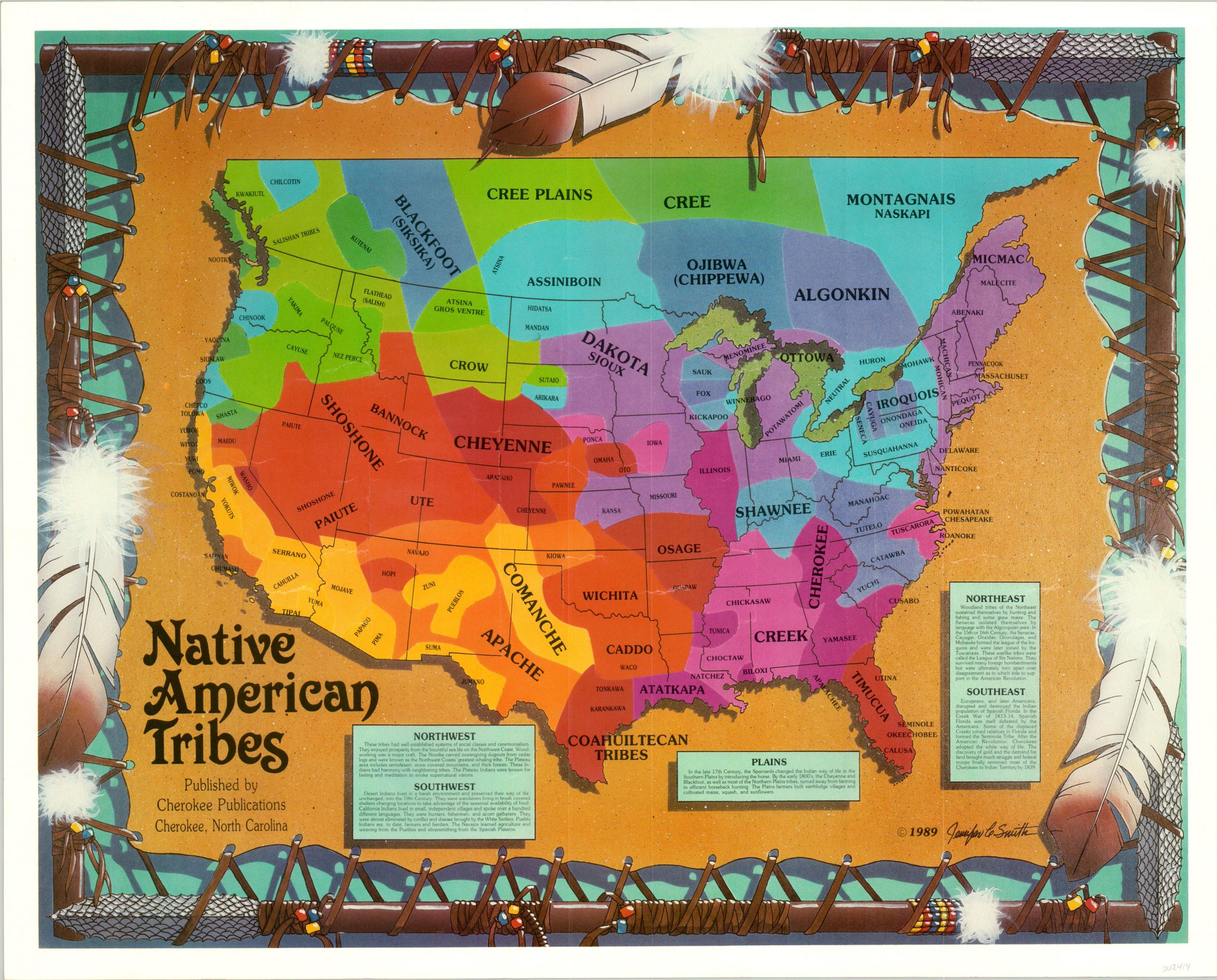

Perhaps the most prominent, though often misunderstood, grouping associated with the San Antonio River were the Coahuiltecans. It’s crucial to understand that "Coahuiltecan" is not the name of a single tribe, but rather an umbrella term applied by ethnographers and historians to dozens, if not hundreds, of small, independent bands who shared similar linguistic roots and cultural patterns across South Texas and northeastern Mexico. Bands like the Payaya, Pacuache, Pajalat, and many others lived in the immediate vicinity of what is now San Antonio.

Their lives were largely nomadic or semi-nomadic, dictated by the availability of food. They hunted small game, fished in the river, and gathered a wide array of plants, including mesquite beans, prickly pear fruit, pecans, and various roots. Their material culture was adapted to their mobile lifestyle, consisting of tools made from stone, bone, wood, and plant fibers. Socially, they were organized into family units and bands, with decisions often made by consensus or through respected elders. Spiritually, they held a profound connection to the natural world, believing in spirits that inhabited animals, plants, and natural phenomena. Their ceremonies and oral traditions, though largely lost due to the devastating impact of colonization, were central to their identity and worldview.

Beyond the Coahuiltecan: Other Riverine and Influential Tribes

While the Coahuiltecans were the primary inhabitants of the immediate San Antonio River area, other significant tribal groups either lived along its broader stretches or exerted considerable influence on the region:

- The Tonkawa: To the north and east of the Coahuiltecans, the Tonkawa were a distinct linguistic and cultural group. They were skilled hunters, particularly of bison, and were known for their distinctive tattoos and their often-turbulent relationships with neighboring tribes. While their primary territory was further north, their movements and interactions frequently brought them into the San Antonio River basin.

- The Karankawa: Dwelling primarily along the Gulf Coast, the Karankawa people’s territory extended to the lower reaches of the San Antonio River as it meandered towards the sea. Known for their unique physical stature, distinctive language, and their mastery of dugout canoes, they were adept at exploiting coastal resources, including fishing, shellfishing, and hunting coastal game. Their presence added another layer of cultural diversity to the river’s Indigenous tapestry.

- The Lipan Apache: As horse culture spread from the north, Apache groups, particularly the Lipan Apache, began to range into South Texas. While not original inhabitants of the immediate river valley, their presence became increasingly significant in the 17th and 18th centuries. They were formidable warriors and skilled hunters, often clashing with both the Spanish and other Indigenous groups. Their pressure from the north often pushed smaller, less militarized groups towards the relative "safety" of the Spanish missions.

- The Comanche: Even further north, the Comanche rose to become the dominant power on the Southern Plains by the 18th century. Their equestrian skills and military prowess made them a force to be reckoned with. While their core territory was well north of San Antonio, their raiding parties and vast hunting grounds extended into the region, impacting Spanish settlements and the smaller Indigenous groups, creating a complex and often dangerous frontier environment.

The Spanish Arrival and the Mission System: A Collision of Worlds

The early 18th century marked a dramatic turning point with the arrival of Spanish missionaries and soldiers. The Spanish vision for Texas involved establishing a chain of missions and presidios (forts) to assert their claim against French encroachment, convert Indigenous peoples to Catholicism, and "civilize" them into loyal Spanish subjects. The San Antonio River, with its abundant water and strategic location, became a focal point for this colonial project.

The establishment of missions like San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo), Concepción, San José, San Juan, and Espada fundamentally altered the lives of the Indigenous peoples. For many Coahuiltecan bands and other smaller groups, the missions represented a complex mix of refuge and subjugation. Faced with increasing pressure from hostile Plains tribes (like the Apache and later the Comanche), devastating European diseases, and the disruption of their traditional hunting and gathering grounds, the missions offered a potential source of food, protection, and a new way of life, albeit one imposed by the Spanish.

Life within the missions was a radical departure from traditional Indigenous ways. Neophytes (as the converted Indigenous people were called) were expected to abandon their languages, spiritual beliefs, and nomadic lifestyles. They were taught Spanish, Catholic doctrine, farming, and various trades. While the missions provided some material benefits, they also brought disease, forced labor, and strict discipline. The cultural suppression within the mission walls led to the erosion of distinct tribal identities, as different bands were often grouped together, their languages and customs gradually fading into a new, syncretic "mission Indian" culture.

The Illusion of Disappearance and the Reality of Resilience

For many years, the prevailing historical narrative suggested that the Indigenous peoples of the San Antonio River "disappeared" into the missions or were wiped out by disease and warfare. While it is true that distinct tribal identities were severely impacted and populations plummeted, the story is far more nuanced and resilient.

Indigenous people did not vanish; they adapted, transformed, and persisted. Many who entered the missions intermarried with other Indigenous groups and eventually with Spanish settlers, creating a mestizo population that carries Indigenous ancestry to this day. Others resisted, fleeing the missions, or retreating to areas beyond Spanish control. Some joined larger, more powerful tribes like the Lipan Apache or Comanche, seeking safety and a new identity.

The "disappearance" was often a linguistic and cultural one, rather than a complete demographic erasure. The languages and many specific cultural practices of the Coahuiltecans, for example, were largely lost, but their genetic legacy and a general sense of Indigenous identity continue in many families throughout South Texas and northern Mexico.

Contemporary Identity and the Reclamation of History

Today, the Indigenous story of the San Antonio River is experiencing a resurgence. Descendants of the original inhabitants, often identifying as Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation or other specific ancestral groups, are actively working to reclaim their history, language, and cultural heritage. They are challenging the colonial narratives, advocating for recognition, and educating the public about the enduring presence and contributions of their ancestors.

This movement is vital for several reasons:

- Historical Accuracy: It ensures a more complete and truthful understanding of Texas history, moving beyond a Eurocentric perspective.

- Cultural Preservation: It supports efforts to revive languages, traditions, and spiritual practices that were suppressed for centuries.

- Identity and Belonging: For descendants, it provides a crucial link to their heritage, fostering a sense of pride and belonging.

- Social Justice: It highlights the ongoing struggles for Indigenous rights, land acknowledgment, and sovereignty.

For the Traveler and Educator: Engaging with Indigenous History

For those visiting the San Antonio River area, or for educators seeking to enrich their curriculum, understanding this Indigenous past is not just an academic exercise; it’s an opportunity for deeper connection and empathy.

- Visit the Missions with a New Lens: While admiring the Spanish architecture of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, remember that these were built by and for Indigenous people. Imagine the daily lives of the mission Indians, their struggles, their resilience, and their adaptation. Look for subtle Indigenous influences in the art and architecture, and consider the Indigenous perspective often missing from traditional interpretations.

- Explore Local Museums: Institutions like the Witte Museum, the Briscoe Western Art Museum, and especially the Institute of Texan Cultures at UTSA offer exhibits that delve into the Indigenous history of Texas, often showcasing artifacts and narratives from a more Indigenous-centered viewpoint.

- Acknowledge the Land: Before beginning any historical tour or educational discussion, take a moment to acknowledge that you are on the ancestral lands of the Coahuiltecan peoples and other Indigenous groups. This simple act is a powerful gesture of respect and recognition.

- Seek Out Indigenous Voices: Look for opportunities to engage with contemporary Indigenous artists, historians, and community leaders. Their perspectives are invaluable for understanding the past and present. Support Indigenous-led initiatives and cultural events.

- Read and Learn: Dive into books, scholarly articles, and documentaries that focus specifically on the Indigenous history of South Texas. Seek out resources written by or in collaboration with Indigenous scholars.

The San Antonio River is more than just a beautiful waterway; it is a profound historical archive, a silent witness to millennia of Indigenous life, struggle, and endurance. By understanding the stories of the Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa, Karankawa, Lipan Apache, and Comanche peoples who shaped this land, we gain a richer, more accurate, and ultimately more human understanding of Texas history. Their legacy is not just etched in the landscape, but lives on in the spirit and descendants of those who called this river home long before it bore a Spanish name. It is a history that deserves to be known, honored, and celebrated.