The Enduring Echoes: A Journey Through Native American Identity Along the Apalachicola River

The Apalachicola River, a vital artery weaving through the Florida Panhandle, is more than just a natural wonder; it is a profound historical tapestry, deeply interwoven with the lives, struggles, and enduring identities of Native American tribes. For millennia, this river and its fertile basin have served as a cradle of culture, a strategic pathway, and a final refuge, bearing witness to the rise and fall of ancient societies, the devastating impact of European contact, and the remarkable resilience of indigenous peoples. Understanding the map of Native American tribes near the Apalachicola River is not merely a geographical exercise; it is an immersion into a complex narrative of adaptation, conflict, and the unwavering spirit of a people tied to their ancestral lands.

Ancient Roots: The Apalachee and the Mississippian Legacy

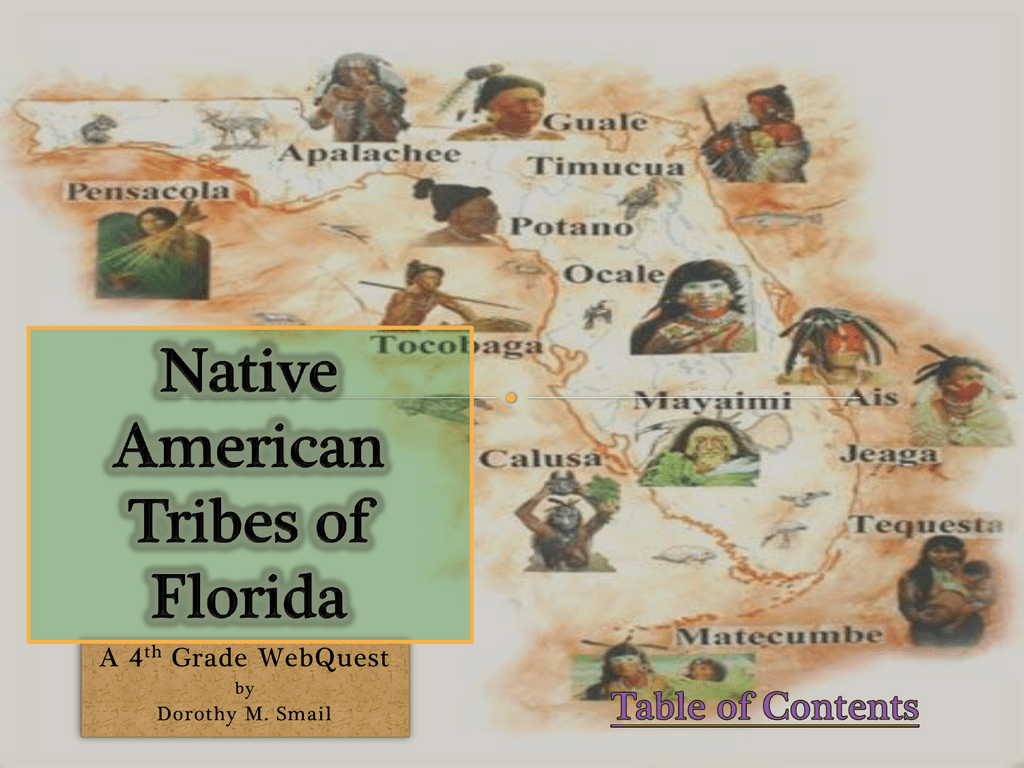

Long before European explorers set foot on its shores, the Apalachicola River basin was a bustling center of Mississippian culture, exemplified most prominently by the Apalachee people. Flourishing from roughly 900 to 1700 CE, the Apalachee were a sophisticated agricultural society, renowned for their extensive cornfields, which fed a populous and organized community. Their villages, often strategically located along waterways and on fertile uplands, were characterized by impressive mound architecture – earthen platforms that supported temples, chiefs’ residences, and ceremonial structures, signifying a complex social and religious hierarchy.

The Apalachee language, a Muskogean dialect, connected them to a broader linguistic family that would later define much of the southeastern United States. Their identity was inextricably linked to the land and its resources. The river provided abundant fish, mussels, and game, while the rich soil yielded bountiful harvests. They were skilled artisans, producing intricate pottery, tools, and ceremonial objects from local materials, and their trade networks extended far beyond the immediate river basin, connecting them with distant tribes across the Southeast.

Their society was structured around powerful chiefdoms, with a strong emphasis on community and ceremony. The Green Corn Dance, a renewal ceremony celebrating the harvest and community solidarity, was a central feature of their spiritual life, a tradition that would persist and evolve among later Muskogean-speaking peoples. The Apalachee were a formidable force, known for their prowess in warfare and their robust economic system, commanding respect and fear among neighboring groups. Their presence defined the region for centuries, leaving an indelible mark on the landscape and shaping the pre-Columbian map of the Florida Panhandle.

The Cataclysm of Contact: European Arrival and Apalachee Decline

The arrival of European explorers in the 16th century irrevocably altered the trajectory of Native American life along the Apalachicola. Hernando de Soto’s brutal expedition in 1539-1540 cut a destructive swathe through Apalachee territory, introducing disease, violence, and disrupting established societal norms. While the Apalachee initially resisted fiercely, the invisible enemy of European pathogens proved far more devastating. Smallpox, measles, and influenza, against which indigenous populations had no immunity, decimated communities, weakening their social structures and reducing their numbers drastically.

By the 17th century, Spanish colonial efforts intensified, particularly through the establishment of missions. While ostensibly aimed at converting Native Americans to Christianity, these missions often served as tools of control and exploitation. The Apalachee were subjected to forced labor, compelled to contribute food and resources to the Spanish garrisons in St. Augustine, and their traditional belief systems were suppressed. Despite their immense suffering, many Apalachee adapted, incorporating elements of Spanish culture while striving to preserve their own. However, their strategic location between the Spanish in Florida and the English in the Carolinas made them vulnerable.

The early 18th century brought the final, devastating blow. English-backed Creek and Yamasee raiding parties, armed with firearms and driven by the lucrative slave trade, launched a series of brutal attacks on the Spanish missions and Apalachee villages. The Apalachee Province was virtually destroyed by 1704. Survivors were either enslaved, fled to other tribes, or sought refuge with the Spanish, who relocated many to new settlements near St. Augustine. The once-dominant Apalachee, as a distinct political and cultural entity along the Apalachicola, largely vanished, their identity absorbed into other groups or scattered across the Southeast. Their story serves as a stark reminder of the devastating human cost of colonization and the fragility of even powerful indigenous societies in the face of overwhelming external forces.

The Emergence of New Identities: The Creek Confederacy

From the ashes of the old world, new Native American identities began to coalesce along the Apalachicola and throughout the Southeast. The vacuum left by the Apalachee’s decline, coupled with the ongoing pressures of European expansion and inter-tribal warfare, led to the formation of powerful new alliances. The most significant of these was the Creek Confederacy, a diverse and expansive political and cultural entity that came to dominate much of what is now Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida.

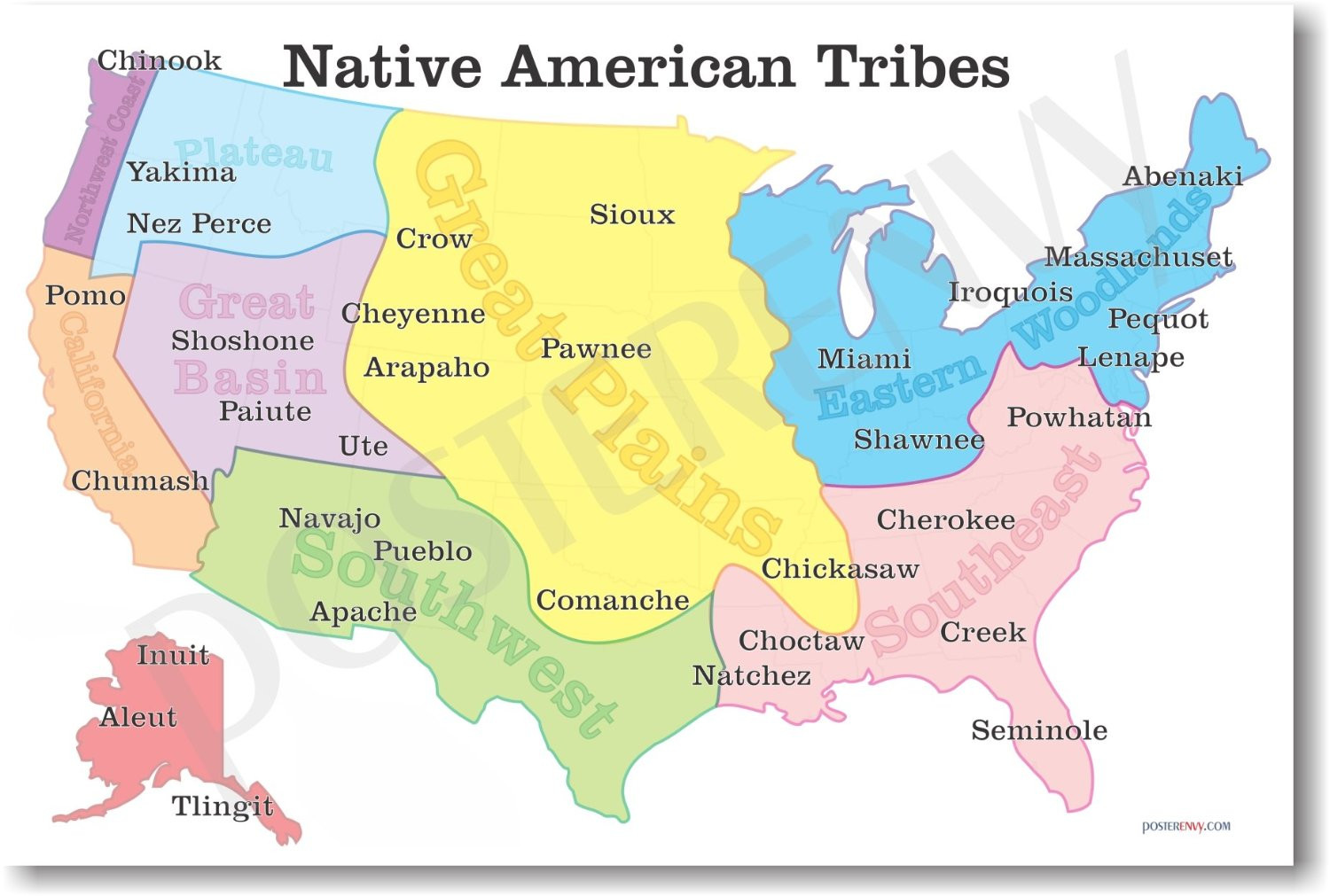

The Creek, or Muscogee people, were not a single tribe but rather a confederation of various linguistic and cultural groups, including remnants of the Apalachee, Timucua, Alabama, Koasati, and others, all speaking dialects of the Muskogean language family. They organized themselves into "Upper Towns" (located primarily along the Coosa and Tallapoosa Rivers) and "Lower Towns" (situated along the Chattahoochee and Apalachicola Rivers). The Apalachicola River region, in particular, became a crucial territory for the Lower Creeks, serving as a gateway to Florida and a vital trade route.

The Creek Confederacy was characterized by a sophisticated political system, with towns operating with a degree of autonomy but united by a shared culture, common laws, and a council system. They were adept diplomats, navigating the complex geopolitical landscape between the British, Spanish, and later, the Americans. Their identity was shaped by a blend of tradition and adaptation. They continued the agricultural practices of their ancestors, cultivated intricate social structures, and maintained the Green Corn Dance as a central unifying ceremony. The Apalachicola River, with its abundant resources, became a core part of their territory, supporting their communities and serving as a strategic frontier.

However, the Creek Confederacy also faced immense internal and external pressures. The early 19th century brought the "Red Stick War" (1813-1814), a civil conflict within the Creek Nation, fueled by internal divisions, religious revivalism, and American expansionist policies. Andrew Jackson’s decisive victory at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend effectively broke the power of the Upper Creeks, leading to significant land cessions. This conflict, and the subsequent American pressure, would have profound implications for the Native American presence along the Apalachicola, giving rise to a new, fiercely independent identity: the Seminoles.

The Seminole: A Distinct Identity Forged in Resistance

The Seminole people, whose name likely derives from the Creek word "simanó-li," meaning "runaway" or "wild ones," emerged as a distinct identity in Florida during the 18th and early 19th centuries. They were a diverse group, primarily composed of Lower Creeks who migrated south to escape American encroachment and internal Creek conflicts, along with remnants of earlier Florida tribes (like the Apalachee and Timucua) and a significant number of runaway enslaved people of African descent, known as Black Seminoles. The Apalachicola River and its surrounding wilderness became a crucial haven and a strategic stronghold for these nascent communities.

The Seminoles forged a new culture, blending Creek traditions with those of other groups and adapting to the unique subtropical environment of Florida. Their identity was defined by their fierce independence, their refusal to submit to American authority, and their determination to preserve their freedom and way of life. They developed a unique martial culture, becoming masters of guerrilla warfare, utilizing the dense swamps and forests of Florida to their advantage.

The Apalachicola River played a pivotal role in the Seminole Wars (1816-1858), a series of brutal conflicts between the Seminoles and the United States. The river served as a natural barrier, a supply route, and a strategic line of defense. Fort Gadsden, established by runaway slaves and Native Americans on the Apalachicola, became a symbol of their resistance before its destruction by U.S. forces in 1816. The First Seminole War (1816-1819) saw Andrew Jackson’s forces invade Spanish Florida, specifically targeting Seminole and Black Seminole settlements along the Apalachicola and Suwannee Rivers.

The Second Seminole War (1835-1842), the longest and costliest Indian war in American history, was a direct result of U.S. efforts to forcibly remove the Seminoles from Florida as part of the broader "Indian Removal" policy. Despite treaties, the Seminoles, led by iconic figures like Osceola, refused to leave their ancestral lands. The Apalachicola River basin was a constant theater of operations, with skirmishes, ambushes, and strategic movements occurring along its banks. Though many Seminoles were eventually forcibly relocated to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) via the "Trail of Tears," a significant number, primarily the Miccosukee and some Muscogee-speaking bands, managed to evade capture by retreating deep into the Everglades, preserving their cultural identity and establishing the modern Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes of Florida.

Enduring Legacy and Modern Echoes

Today, the Apalachicola River continues to echo with the stories of these resilient peoples. While the Apalachee as a distinct political entity vanished centuries ago, their descendants exist, having been absorbed into other tribes or having migrated and re-established communities elsewhere (such as the Apalachee Nation of Mexico, FL). The Creek Confederacy, though significantly altered by removal, continues to thrive as the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in Oklahoma, and smaller bands and descendants remain in the Southeast.

The Seminole and Miccosukee Tribes of Florida stand as powerful testaments to the enduring spirit of resistance and cultural preservation. They have maintained their distinct identities, languages, and traditions against overwhelming odds, and their reservations in Florida are vibrant centers of culture, tourism, and economic development. Visitors to the Apalachicola region can find traces of this rich history in various forms: archaeological sites, historical markers, and state parks that interpret the lives of these early inhabitants. The river itself, with its ancient currents, serves as a living museum, connecting the present to a past teeming with human endeavor, cultural richness, and profound struggle.

To truly appreciate the Apalachicola River is to understand its deep indigenous roots. It is to recognize that the land was not empty but was shaped by the hands, beliefs, and struggles of generations of Native Americans. Their history is not merely a chapter in a textbook; it is a vital, living narrative that continues to inform the identity of the region and offers profound lessons in resilience, adaptation, and the enduring connection between people and their ancestral lands. As travelers explore this beautiful region, a deeper appreciation emerges when one listens for the enduring echoes of the Apalachee, the Creek, and the Seminole, whose spirits remain intertwined with the ancient flow of the Apalachicola River.