Uncharted Waters: Reimagining the Map of Native American Transoceanic Voyages

The conventional narrative of the Americas often begins with "discovery" by Europeans, painting a picture of two isolated hemispheres suddenly colliding in 1492. This Eurocentric view, however, increasingly gives way to a more complex, interconnected past, one where oceans were not insurmountable barriers but potential highways. Imagine a map, not of colonial conquests, but of pre-Columbian transoceanic voyages – a conceptual chart illustrating the journeys, accidental drifts, and cultural exchanges that may have linked the Americas to the wider world long before Columbus. Such a map would fundamentally reshape our understanding of history and affirm the sophisticated maritime capabilities and global awareness of Indigenous peoples.

This reimagined map challenges the very notion of "discovery" by highlighting pre-existing connections and the agency of Native American mariners. It’s a map built not just on archaeological finds, but also on ethnobotany, linguistics, genetics, and even the reinterpretation of ancient oral traditions.

The Americas as a Destination: Norse Encounters

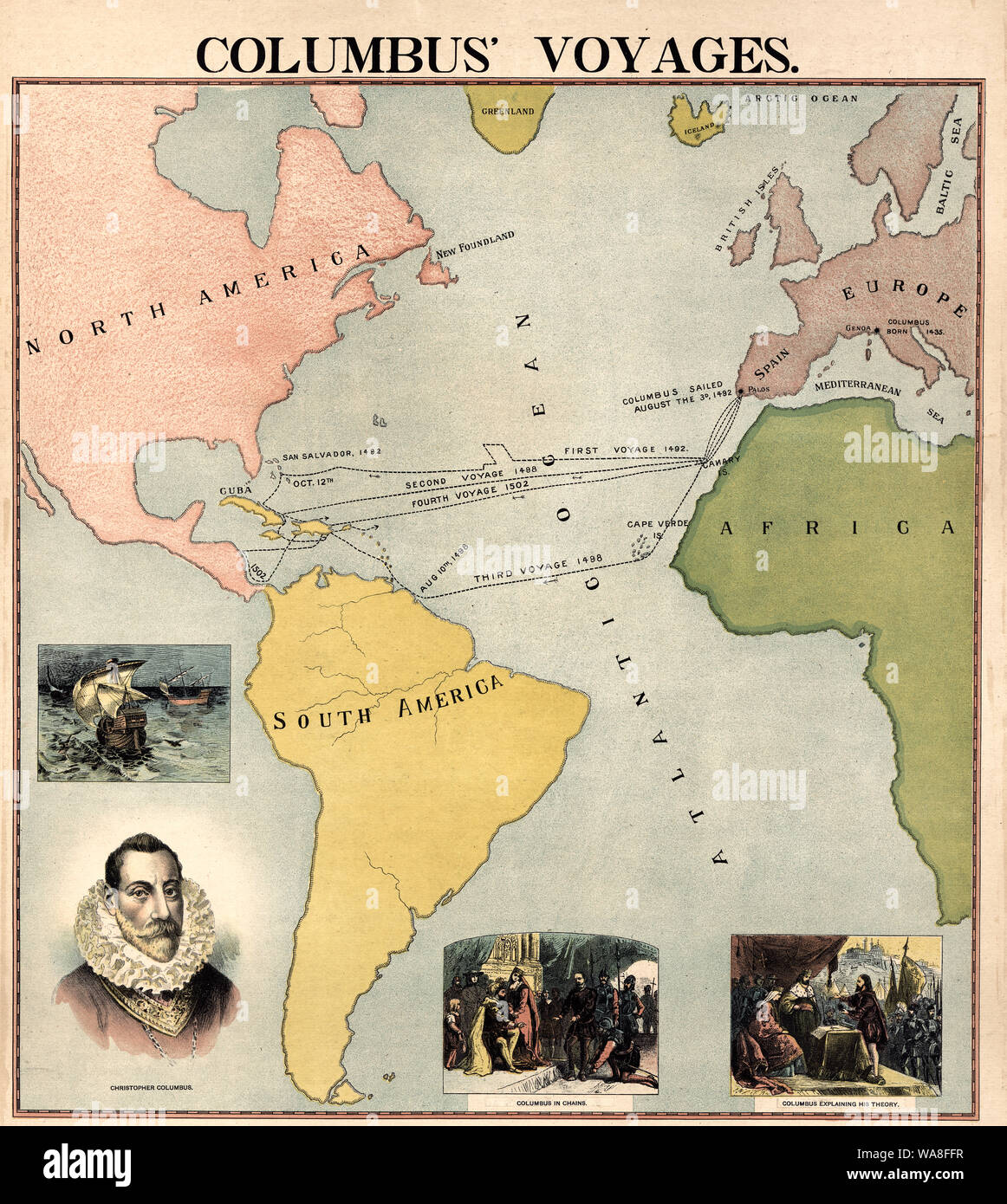

One of the most firmly established points on this conceptual map would be the Norse landings in North America. Around 1000 CE, Vikings, led by Leif Erikson, sailed from Greenland to a land they called Vinland, now definitively identified with L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland, Canada. Archaeological excavations have uncovered distinct Norse longhouses, workshops, and artifacts, providing irrefutable evidence of a European presence in the Americas five centuries before Columbus.

The Norse sagas, particularly the "Saga of Erik the Red" and the "Saga of the Greenlanders," vividly describe their encounters with Indigenous peoples, whom they called "Skraelings." These interactions ranged from trade to conflict, illustrating that the Americas were not an empty wilderness awaiting discovery, but a populated continent with established societies capable of defending their territories. This early contact, though ultimately short-lived and without lasting colonial impact, irrevocably places North America on a transoceanic map of human movement, challenging the isolationist paradigm. It proves that the Atlantic was navigable from East to West by advanced maritime cultures of the era.

The Pacific Highway: Polynesian-South American Exchange

Perhaps the most compelling and robust evidence for pre-Columbian transoceanic contact involves the vast Pacific Ocean, specifically between Polynesia and South America. This section of our map would be crisscrossed with theoretical routes, primarily originating from Polynesia but with strong implications for Native American involvement.

The most famous piece of evidence is the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas). This staple crop is native to the Americas but was widely cultivated across Polynesia centuries before European contact. The linguistic evidence is equally striking: the Quechua word for sweet potato, "kumara," closely resembles the Polynesian "kumala" or "kumara." Genetic studies confirm the American origin of the Polynesian sweet potato varieties. How did it get there? The prevailing theory is that Polynesian navigators, renowned for their incredible seafaring skills and voyaging canoes, sailed eastward to the coast of South America, acquired the sweet potato, and successfully transported it back across thousands of miles of open ocean.

However, the reverse journey – Native Americans reaching Polynesia – cannot be entirely discounted. The balsa raft technology of ancient Peruvians, exemplified by Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki expedition (a deliberate recreation, not an actual historical voyage), demonstrated the feasibility of such a journey. While Heyerdahl’s specific claims about direct South American colonization of Polynesia are largely disputed, the expedition undeniably showcased the seaworthiness of Indigenous American vessels.

Further strengthening the case for two-way or Indigenous American contact is the discovery of pre-Columbian chicken bones in Chile with Polynesian DNA. This suggests that chickens, native to Asia and introduced to Polynesia, somehow made their way to South America before European arrival. While Polynesians bringing chickens to South America is a strong possibility, it also opens the door to more complex interactions, potentially involving Native American mariners.

The evidence from the Pacific is crucial because it demonstrates not just fleeting contact, but successful, sustained exchange of vital resources and knowledge across immense distances. It paints a picture of Indigenous peoples on both sides of the Pacific as sophisticated navigators, agriculturalists, and cultural disseminators, actively participating in a global network of exchange.

The Enigmatic Atlantic Crossings: Theories and Speculations

While the Norse and Polynesian connections are supported by strong evidence, other proposed pre-Columbian transoceanic voyages across the Atlantic remain far more speculative, yet they form a vital part of our conceptual map, highlighting ongoing debates and the limitations of current archaeological understanding.

African Theories and the Olmec Connection:

One of the most provocative theories involves potential pre-Columbian contact between West Africa and Mesoamerica, particularly the Olmec civilization (c. 1200-400 BCE). Proponents, most notably Ivan Van Sertima in "They Came Before Columbus," point to stylistic similarities between Olmec colossal heads and West African facial features, as well as shared cultural traits like pyramid building, mummification practices, and specific botanical similarities (e.g., the cotton species Gossypium barbadense). Van Sertima suggests that West African mariners, perhaps from the powerful Mali Empire, could have crossed the Atlantic. Indeed, historical accounts from the 14th century, such as those by Al-Umari, describe the predecessor of Mansa Musa sending two large expeditions across the Atlantic, with only one returning to report on their findings.

Critics, however, largely dismiss these claims, attributing facial similarities to artistic conventions or coincidental convergences, and shared cultural traits to independent invention. The lack of definitive African artifacts in pre-Columbian Mesoamerican archaeological sites or vice-versa remains a significant hurdle. Nevertheless, these theories compel us to consider the maritime capabilities of ancient African civilizations and the potential for drift voyages or even deliberate expeditions across the Atlantic, expanding the scope of our conceptual map to include an African-American corridor.

Other European Speculations (Beyond the Norse):

Tales of early European voyages to the Americas prior to Columbus also punctuate our map, though with even less conclusive evidence. The legend of St. Brendan the Navigator, an Irish monk, describes a miraculous voyage across the Atlantic in the 6th century in a leather boat, reaching a "Promised Land of the Saints." While a modern recreation proved the journey’s feasibility, no archaeological evidence supports Brendan’s actual arrival in the Americas.

Similarly, claims of Phoenician or Roman contact often rest on disputed artifacts, such as the infamous Paraíba inscription in Brazil (a hoax) or isolated finds of Roman coins in the Americas, which are generally dismissed as post-Columbian losses or hoaxes. These theories, while captivating, currently lack the rigorous archaeological and scientific backing to be firmly placed on our map of proven voyages.

Native American Voyages Outward: The Missing Links?

The most challenging, yet crucial, aspect of our "Map of Native American Transoceanic Voyages" is evidence of Indigenous peoples from the Americas themselves undertaking significant, documented voyages to other continents. While the sweet potato’s presence in Polynesia strongly suggests either Polynesians returning from the Americas or Native Americans voyaging to Polynesia, direct, unambiguous evidence of Native Americans landing in Europe, Africa, or Asia and leaving a lasting mark is scarce.

However, the absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence. The maritime capabilities of various Native American groups were considerable. Peoples like the Caribs and Arawaks in the Caribbean, the Chinook on the Pacific Northwest coast, and the Inuit in the Arctic were expert navigators and boat builders, constructing canoes and umiaks capable of long-distance travel, sometimes over a thousand miles along coastlines or to distant islands. While these were primarily coastal or inter-island voyages, they demonstrate sophisticated seafaring knowledge and technology.

Accidental drift voyages, especially from West Africa to the Americas, are well-documented post-Columbian (e.g., enslaved Africans escaping shipwrecks), and the reverse is also theoretically possible given favorable currents. The potential for such accidental, or even deliberate but undocumented, voyages from the Americas to other continents exists. The map acknowledges this possibility, marking it as an area of active research and speculation, urging a re-examination of global history through an Indigenous lens.

Reclaiming History and Identity

This conceptual map of transoceanic voyages is far more than an academic exercise; it is a powerful tool for reclaiming history and affirming Indigenous identity.

- Challenges Eurocentrism: By demonstrating pre-Columbian global connections, it dismantles the myth of European "discovery" and places Indigenous peoples as active agents in a larger, interconnected human story, rather than passive recipients of European influence.

- Highlights Indigenous Ingenuity: The map showcases the incredible maritime technology, navigational skills, and ecological knowledge of Indigenous peoples. From Polynesian star navigators to South American balsa raft builders and North American longboat experts, these were not isolated, static societies, but dynamic cultures capable of remarkable feats of exploration and exchange.

- Reframes "Isolation": The Americas were never truly isolated. They were part of a global web of contact, albeit one with different pathways and intensities than post-Columbian interactions. This understanding enriches the tapestry of human migration and cultural diffusion.

- Promotes Interdisciplinary Research: Constructing this map requires collaboration across archaeology, genetics, linguistics, oceanography, and the careful study of oral traditions, which often hold clues to ancient movements and interactions.

- Educational and Travel Impact: For a travel and education blog, this perspective is transformative. It encourages visitors to Indigenous lands to look beyond simplistic narratives and appreciate the profound history, resilience, and global contributions of Native American cultures. It fosters a deeper respect for Indigenous knowledge systems and challenges us to see Indigenous communities not as relics of the past, but as inheritors of a dynamic, globally connected heritage.

Conclusion

The "Map of Native American Transoceanic Voyages" is not a static artifact but a dynamic, evolving concept. It is a testament to the human spirit of exploration and connection that transcends continents and centuries. By acknowledging the Norse in the North Atlantic, the Polynesians in the Pacific, and critically examining the possibilities across the South Atlantic, we begin to sketch a far richer, more nuanced, and respectful history of the Americas. This map reminds us that the narrative of human civilization is one of constant movement, exchange, and adaptation, a story in which Indigenous peoples played central, active roles long before the arrival of European ships in 1492. It invites us to explore, question, and ultimately, to embrace a truly global history.