Beyond the Borders: Mapping Native American Traditional Justice – A Journey Through History, Identity, and Resilience

Forget the standard political maps that delineate states and countries with rigid lines. To truly understand justice among Native American nations, one must embark on a journey across an invisible, dynamic map – a landscape of interwoven histories, profound cultural identities, and enduring resilience. This is not a map of physical territories alone, but a complex overlay of traditional law, spiritual principles, community structures, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination. For the curious traveler and the dedicated educator, understanding this map offers a vital window into the soul of Indigenous peoples and their unique contributions to the concept of justice.

The Invisible Map: What is Traditional Justice?

At its heart, Native American traditional justice differs fundamentally from the Western adversarial system. While the latter often focuses on punishment, individual guilt, and state-sanctioned retribution, Indigenous systems are overwhelmingly restorative, holistic, and community-centered. They prioritize healing – for the victim, the offender, and the entire community – aiming to re-establish balance and harmony rather than simply assigning blame. This "map" is charted not by statutes and courtrooms alone, but by a deep understanding of interconnectedness, the sacredness of relationships, and the long-term well-being of the collective.

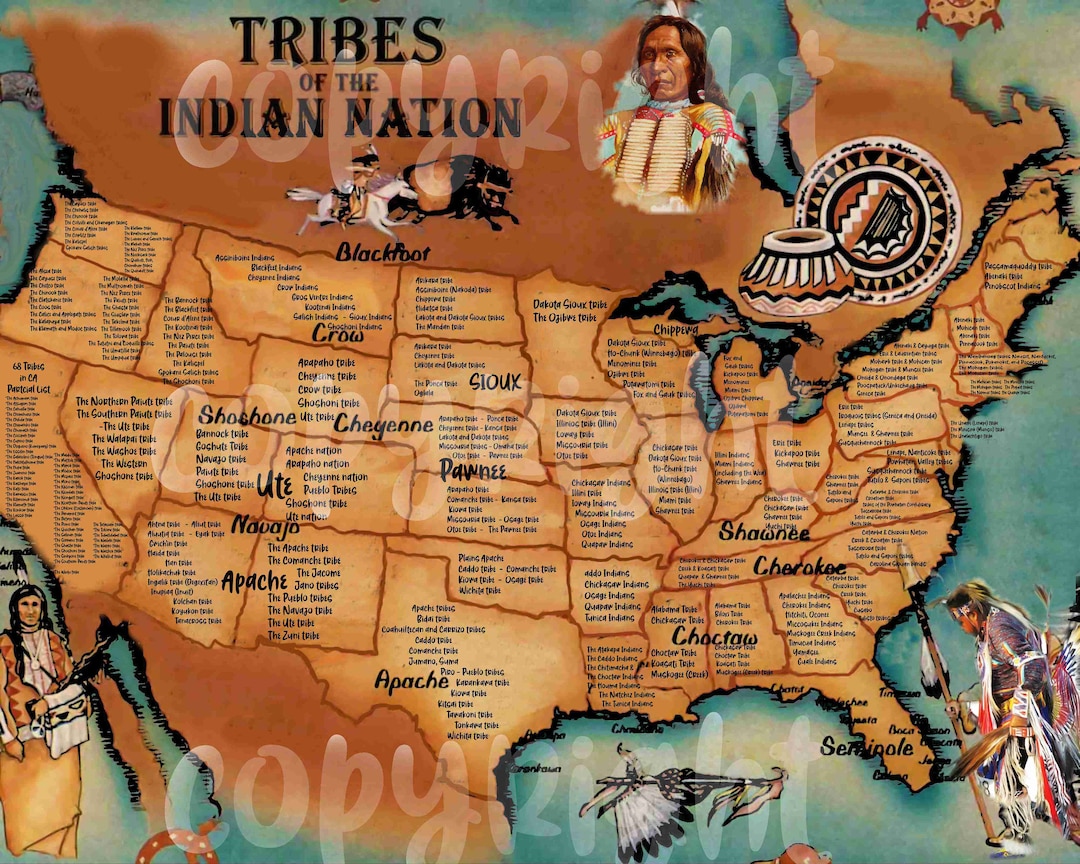

This invisible map is incredibly diverse. With over 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States alone, and many more unrecognized or in Canada (First Nations) and Mexico, there is no single "Native American justice system." Each nation, shaped by its unique history, language, spiritual beliefs, and environment, developed distinct practices. However, common threads emerge: the emphasis on consensus-building, the wisdom of elders, the power of ceremony, and the understanding that an offense against one is an offense against all.

Historical Coordinates: Pre-Colonial Justice Systems

Before the arrival of European colonizers, Native American nations possessed sophisticated, self-governing legal and social structures. Their justice systems were intricately woven into their daily lives, often inseparable from their spiritual beliefs and social organization.

For many nations, the family, clan, or extended kinship group was the primary unit of social control and justice. Disputes were often resolved within these groups, with elders playing crucial roles as mediators and decision-makers. The concept of "blood law" among some nations, like the Cherokee, illustrates an early form of restorative balance, where an offense against a clan member might require restitution or even a life from the offender’s clan to restore equilibrium – though this system evolved significantly over time.

The Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, for example, developed the Great Law of Peace (Kaianere’kó:wa), a complex constitutional system that governed their five (later six) nations. This law emphasized peace, power, and righteousness, establishing councils, procedures for resolving disputes, and a framework for inter-tribal relations that predated many European concepts of democratic governance. Their system prioritized deliberation, consensus, and the long-term welfare of the people, demonstrating an advanced understanding of governance and conflict resolution.

Justice was often administered through public forums, ceremonies, or council meetings where all community members, or at least representatives, could participate. The goal was not to "win" a case, but to find a resolution that addressed the harm, repaired relationships, and ensured the continued health of the community. Ostracization or banishment, rather than incarceration, were common forms of severe punishment, as being cut off from the community was often considered the ultimate hardship. These systems were deeply rooted in the land, the seasons, and the spiritual world, reflecting a worldview where humans were part of a larger, interdependent web of life.

The Seismic Shift: Colonization and the Imposition of Western Law

The arrival of European powers marked a catastrophic disruption of these indigenous justice systems. The colonial project, driven by land acquisition, resource extraction, and cultural assimilation, systematically undermined Native American sovereignty and legal traditions. This period represents a dark chasm on our invisible map, where traditional pathways were obliterated or forcibly suppressed.

Early colonial policies often ignored or directly suppressed Native American legal authority. As the United States expanded, it enacted a series of laws and policies designed to dispossess Native nations of their land and force them into conformity with Western norms. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, the establishment of reservations, and the subsequent allotment policies (like the Dawes Act) fractured communities and eroded the land base upon which traditional justice systems depended.

A crucial turning point was the Major Crimes Act of 1885, which asserted federal jurisdiction over seven major crimes (later expanded) committed by Native Americans on reservations. This was a direct infringement on tribal sovereignty and a profound blow to the authority of tribal courts and traditional leaders. It essentially created a dual system where some crimes fell under federal jurisdiction, others under tribal, and states often asserted jurisdiction in complex ways. Public Law 280 (1953) further complicated matters by unilaterally transferring criminal and some civil jurisdiction over Native Americans in certain states from the federal government to state governments, often without tribal consent.

These legislative actions, coupled with the devastating impact of boarding schools that aimed to "kill the Indian to save the man," systematically dismantled traditional governance, languages, and cultural practices – all of which were integral to Indigenous justice. Generations were traumatized, losing connection to their heritage and, by extension, their traditional ways of resolving conflict and maintaining social order. The invisible map became fragmented, with traditional routes obscured by imposed, alien legal structures.

Navigating the Resurgence: Contemporary Traditional Justice Practices

Despite centuries of assault, Native American traditional justice systems have demonstrated remarkable resilience. The self-determination era, beginning in the 1970s, ushered in a period of renewed tribal sovereignty and the revitalization of Indigenous governance. This period saw many nations re-establishing tribal courts, developing their own legal codes, and, significantly, reviving or adapting traditional justice practices.

Today, the invisible map is being redrawn and reclaimed. Many tribal courts now blend elements of Western legal frameworks with traditional principles. However, a growing movement emphasizes the return to purely traditional or deeply culturally informed methods, often termed "peacemaking" or "healing justice."

Navajo Peacemaking (Hózhóogo Naat’áanii) is a prominent example. Based on the Diné philosophy of Hózhó (harmony and balance), peacemaking councils led by respected elders resolve disputes through dialogue, mediation, and a focus on restoring relationships. Unlike a Western court, which might assign guilt and punishment, peacemaking aims to understand the root causes of conflict, encourage confession and apology, and facilitate agreements that bring the parties back into harmony with themselves, their families, and the community. This often involves specific ceremonies, prayer, and a deep respect for the wisdom of the collective.

Other tribes have implemented variations of restorative justice circles, healing-to-wellness courts (drug/alcohol courts that integrate cultural practices and traditional healing), and elder councils. These systems are not about being "soft on crime" but about being effective at addressing the underlying issues that lead to harm, fostering accountability, and preventing future offenses by building stronger, healthier communities. They recognize that justice is not just about individuals, but about the intricate web of relationships that define a community.

Identity, Sovereignty, and the Future of the Map

The revitalization of traditional justice is inextricably linked to Indigenous identity and sovereignty. For Native nations, the ability to define and administer their own justice is a fundamental expression of their right to self-governance and cultural preservation. It is a powerful act of decolonization, asserting that their ancient ways hold wisdom and efficacy that Western systems often lack.

The "map" of Native American traditional justice is therefore a living, breathing entity, constantly evolving while remaining anchored to deep historical and cultural roots. It is a testament to the enduring power of Indigenous identity, language, and spiritual practices. Elders, fluent in their native tongues and steeped in generational knowledge, are vital cartographers of this map, guiding communities back to pathways of healing and balance.

However, challenges persist. Jurisdictional complexities remain a significant hurdle, particularly in cases involving non-Native offenders on tribal lands or "Major Crimes" where federal jurisdiction often overrides tribal authority. Underfunding of tribal courts and justice programs, the pervasive impact of intergenerational trauma from historical injustices, and the ongoing struggle for recognition and respect from dominant legal systems are constant battles.

For the Traveler and Educator: Navigating with Respect

For those interested in exploring this profound aspect of Native American culture, whether as a traveler seeking deeper understanding or an educator sharing knowledge, a few principles are paramount:

- Recognize Sovereignty: Understand that Native American nations are sovereign entities with their own governments, laws, and justice systems. Respect their authority and jurisdiction.

- Listen and Learn: Seek out information directly from Native communities, scholars, and tribal governments. Avoid relying solely on non-Native interpretations. Attend cultural events (when appropriate and invited) and engage with educational materials provided by tribes.

- Appreciate Diversity: Remember there is no single "Native American" culture or justice system. Learn about the specific traditions of the nation you are visiting or studying.

- Understand the "Why": Focus on the underlying principles of traditional justice – healing, restoration, community well-being – rather than simply comparing it to Western systems.

- Support Indigenous Initiatives: If you wish to contribute, support Native-led organizations working on justice reform, cultural revitalization, and self-determination.

Conclusion: A Map for All Humanity

The map of Native American traditional justice is not confined to reservation borders or ancient texts; it is a conceptual framework that offers profound lessons for all societies. It challenges us to look beyond punitive measures and individual blame, encouraging us to consider the health of the entire community, the power of restorative dialogue, and the deep wisdom embedded in cultural traditions.

This invisible map, etched by centuries of history, resilience, and unwavering identity, reveals pathways toward healing and harmony that are more vital than ever in a fractured world. To truly understand it is to gain not just knowledge of a unique legal system, but a deeper appreciation for the interconnectedness of all life and the enduring power of human spirit in the pursuit of genuine justice. It is a journey well worth taking, offering insights that transcend borders and enrich our collective understanding of what it means to be a just society.