The Woven Landscape: A Map of Native American Textile Arts, History, and Identity

Imagine a map of North America, not delineated by modern political borders, but by brilliant threads, intricate patterns, and the deep hues of natural dyes. This is the "Map of Native American Textile Arts"—a living, breathing atlas where each stitch, bead, and weave chronicles centuries of history, embodies profound cultural identity, and charts the resilience of Indigenous peoples. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this textile cartography offers an unparalleled journey into the heart of Native American heritage.

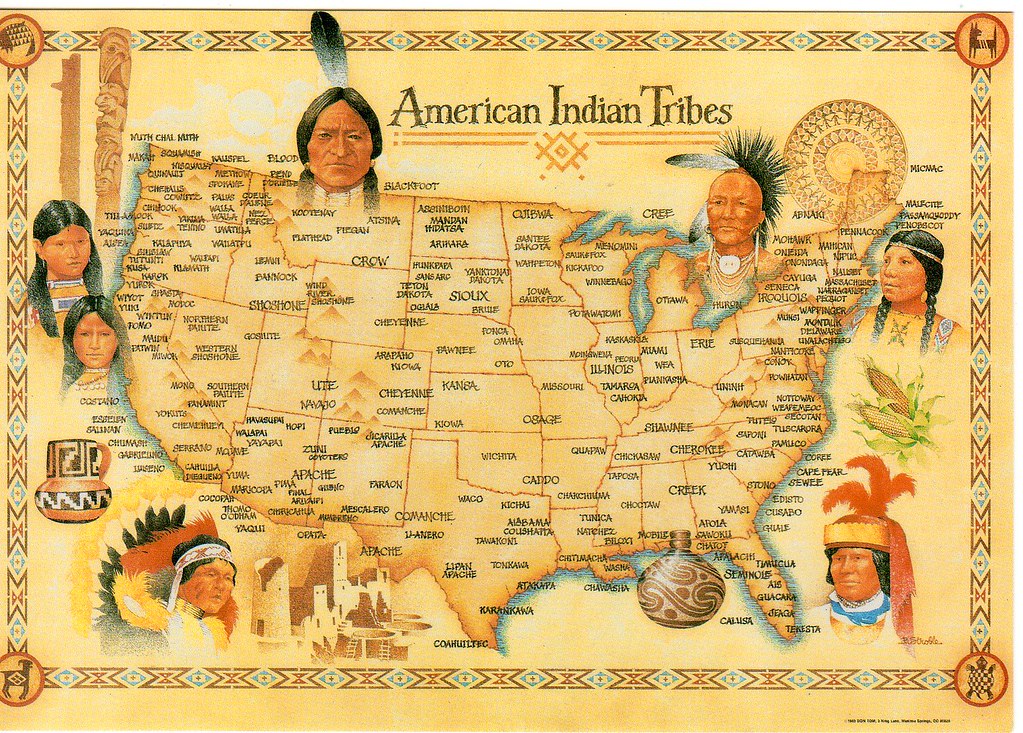

This is not a static parchment, but a dynamic, ever-evolving landscape of artistic expression. From the arid deserts of the Southwest to the lush forests of the Northwest Coast, from the vast plains to the dense woodlands of the East, distinct textile traditions emerged, shaped by environment, spiritual beliefs, social structures, and interactions with neighboring tribes and, later, European newcomers. Each regional style represents a unique dialect in the grand language of Indigenous art, speaking volumes about the land and its people.

Mapping the Threads: A Regional Overview

The Southwest: Geometric Narratives and Sacred Weaves

The Southwest is perhaps the most iconic region on our textile map, dominated by the unparalleled weaving traditions of the Navajo (Diné) people. For centuries, Diné weavers have transformed Churro sheep wool into masterpieces of color and design – rugs and blankets that are both utilitarian and profoundly artistic. Early Navajo "Chief Blankets" were prized trade items, their bold stripes and later, complex geometric patterns, signifying status and wealth. With the introduction of the vertical loom and new dye colors, styles diversified, leading to regional variations like the vibrant Ganado Red, the intricate Two Grey Hills, and the pictorial Teec Nos Pos designs. Each pattern often holds symbolic meaning, connecting the weaver to the land, cosmology, and generations of knowledge.

Beyond the Navajo, the Pueblo peoples (Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, etc.) are renowned for their cotton textiles, particularly ceremonial sashes, kilts, and blankets, often adorned with embroidery and designs reflecting agricultural cycles, rain, and fertility. Hopi overlay weaving, with its distinctive two-layer technique, creates stunning graphic imagery. These textiles are not merely decorative; they are integral to spiritual ceremonies, embodying prayers and cultural narratives.

The Plains: Beadwork and Quillwork, Stories of Power and Spirit

Moving north to the vast expanse of the Great Plains, the map shifts to a vibrant mosaic of beadwork and porcupine quillwork. Tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfeet mastered the art of adorning hides, clothing, bags, and ceremonial objects with intricate designs. Before the introduction of glass beads by Europeans, porcupine quills were meticulously flattened, dyed, and sewn onto buckskin, creating geometric patterns that often symbolized natural elements or spiritual visions.

The arrival of glass beads revolutionized this art form. Plains beadwork became an explosion of color and detail, depicting everything from abstract geometric patterns to realistic scenes of buffalo hunts and battles. Each bead, painstakingly sewn, contributed to a narrative or a symbol of personal achievement, tribal identity, or spiritual protection. War shirts, moccasins, pipe bags, and cradleboards became canvases for these powerful artistic expressions, worn as statements of identity and spiritual strength.

The Northwest Coast: Crests, Clans, and Chilkat Majesty

Along the rugged Pacific coastline, from what is now Alaska down through British Columbia and into Washington state, the textile map reveals another distinct and breathtaking tradition: the Chilkat and Ravenstail weaving of tribes like the Tlingit, Haida, and Kwakwaka’wakw. These ceremonial blankets, made from mountain goat wool and cedar bark, are instantly recognizable by their complex "formline" designs – curvilinear shapes that depict stylized animals (raven, bear, wolf, eagle) and ancestral crests.

Chilkat weaving is unique in that the patterns are woven directly into the fabric, rather than being applied afterwards. The weft threads are twined around warp threads, allowing for the creation of intricate, symmetrical designs that appear to flow. These blankets are not only stunning works of art but also powerful symbols of clan identity, status, and spiritual connection, worn during potlatches and other significant ceremonies. The equally intricate Ravenstail weaving, characterized by geometric patterns and a unique three-strand braid, also demonstrates the profound technical skill and aesthetic sensibilities of these coastal peoples.

The Eastern Woodlands & Northeast: Wampum, Finger Weaving, and Forest Fibers

In the dense forests and along the waterways of the Eastern Woodlands, our map shows a different set of textile traditions. Here, the Iroquois Confederacy, Ojibwe, Wampanoag, and other tribes utilized materials like bark, natural fibers, and shells. Wampum, made from carefully drilled and strung quahog and whelk shells, was more than adornment; it served as a medium for recording history, treaty agreements, and spiritual messages. Wampum belts, with their symbolic patterns, were crucial in diplomacy and community governance.

Porcupine quillwork also flourished in the Northeast, particularly among the Ojibwe and Huron, where quills were dyed and applied to birchbark boxes, clothing, and moccasins, often depicting floral motifs and geometric designs inspired by the natural world. Finger weaving, a technique of interlacing threads without a loom, produced intricate sashes and belts, particularly among the Métis and other Woodland tribes, known for their vibrant colors and chevron patterns. Basketry, utilizing splints of black ash, sweetgrass, and birch bark, was also highly developed, with both utilitarian and ceremonial forms.

The Southeast: Patchwork, Pine Needles, and River Cane

The Southeastern United States, home to tribes like the Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, and Muscogee (Creek), showcases textile arts adapted to a humid, resource-rich environment. The Seminole people are particularly famous for their vibrant patchwork clothing, a distinctive art form that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Strips of brightly colored fabric are cut into geometric shapes and sewn together to create intricate, repetitive patterns that adorn shirts, skirts, and jackets. This art form became a powerful symbol of Seminole identity and resilience in the face of forced removal and assimilation.

Basketry also thrives in the Southeast, with materials like river cane, pine needles, and split oak being expertly woven into a variety of shapes and sizes. Cherokee double-weave baskets, for example, are renowned for their strength and intricate patterns, showcasing a deep connection to the natural resources of their ancestral lands.

California & Great Basin: Masterful Basketry

In the diverse landscapes of California and the Great Basin, basketry reigns supreme. Tribes such as the Pomo, Washoe, Paiute, and Yokuts created some of the most technically advanced and aesthetically stunning baskets in the world. Using incredibly fine fibers from sedge, willow, and juncus, these weavers achieved astonishingly tight weaves, often so fine they were watertight. Baskets served myriad purposes – for gathering, storage, cooking (using hot stones), and ceremony. The designs, often geometric or featuring subtle animal motifs, are a testament to the weavers’ patience, skill, and profound understanding of their local environment. Washoe weaver Louisa Keyser (Dat So La Lee) became particularly famous for her exquisite coiled degikup baskets.

The Threads of History: From Ancient Roots to Modern Revival

The history woven into this textile map is as complex and layered as the art itself.

Pre-Contact Sophistication: Long before European arrival, Indigenous peoples across North America developed sophisticated textile technologies. Cotton was cultivated in the Southwest, yucca and other plant fibers were processed for cordage and weaving, and animal hides and furs were tanned and decorated. The skills involved—spinning, dyeing with natural pigments from plants and minerals, and various weaving and sewing techniques—were passed down through generations, forming the bedrock of cultural identity.

European Contact and Adaptation: The arrival of Europeans brought profound changes. While initially disruptive, new materials like glass beads, commercial wool, and aniline dyes were quickly adopted and integrated into existing traditions, often leading to innovative artistic expressions. Navajo weavers, for instance, readily incorporated commercial yarn and new color palettes into their rugs. Plains tribes embraced glass beads, creating the vibrant beadwork we recognize today. However, this period also saw the suppression of many cultural practices, forced relocations, and the devastating impact of disease, which threatened the survival of these art forms.

Resilience and Revival: Despite immense pressures, Native American textile arts endured. Many traditions were maintained in secret or passed down within families. The 20th century witnessed a significant revival, fueled by a renewed interest in Indigenous cultures, the establishment of tribal cultural centers, and the dedication of artists to reclaim and innovate upon their heritage. Today, Native American textile artists are celebrated globally, their work collected by museums and art enthusiasts, and their skills taught to new generations, ensuring the continuity of these vital cultural expressions.

Identity Woven In: More Than Just Art

For Native American peoples, textile arts are far more than decorative objects; they are profound carriers of identity, history, and spirituality.

Storytelling and Oral Tradition: Each pattern, color, and design often tells a story—of creation, migration, personal experience, or tribal history. A Navajo rug might depict a storm pattern, symbolizing balance and the forces of nature. A Plains beadwork design might commemorate a warrior’s deed or a spiritual vision. These visual narratives reinforce oral traditions and connect individuals to their ancestral past.

Spiritual Connection: Many textile arts are imbued with spiritual significance, used in ceremonies, rituals, and as offerings. The act of creation itself can be a meditative and spiritual practice, connecting the artist to the materials, the land, and the spiritual world. The symbolism woven into a piece often reflects a deep respect for nature and the interconnectedness of all life.

Community and Status: Textile arts play a crucial role in defining community and individual status. Skill in weaving or beadwork is highly respected, and master artists are revered. Specific designs or materials might be reserved for leaders or used to signify clan affiliation, marital status, or achievements. The sharing of knowledge and techniques within families and communities strengthens social bonds.

Economic and Cultural Survival: In contemporary times, the creation and sale of textile arts also contribute significantly to the economic well-being of Native American communities, providing livelihoods for artists and their families. Moreover, these arts serve as powerful statements of cultural sovereignty and resilience, asserting Indigenous presence and identity in a world that has often sought to erase them.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging with the Woven Map

For those embarking on a journey through Native American lands, understanding this woven map enriches the experience immeasurably.

- Visit Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums: These institutions are invaluable resources, offering context, historical insights, and opportunities to see exquisite examples of textile arts firsthand.

- Support Native Artists Directly: Whenever possible, purchase art directly from the creators at tribal markets, art fairs, or through galleries that ethically represent Indigenous artists. This ensures fair compensation and supports the continuation of these traditions.

- Learn About Authenticity: Be mindful of "faux-Native" goods. Seek out authentic, handmade pieces and learn to recognize the hallmarks of quality and traditional techniques.

- Engage with Respect: Approach these art forms with respect and an open mind. Understand that each piece carries a legacy of history, culture, and personal expression.

The Map of Native American Textile Arts is not merely a collection of beautiful objects; it is a profound testament to human creativity, adaptability, and an enduring connection to land and spirit. Each thread is a whispered history, each pattern a declaration of identity, inviting us to look closer, listen deeper, and appreciate the rich, vibrant tapestry of Indigenous North America. To trace this map is to embark on a journey of discovery, woven through time and across the diverse landscapes of a continent.