A Sacred Geography: Navigating the Map of Native American Spiritual Sites

The landscape of North America is not merely a collection of geographical features; it is a profound spiritual map, etched with millennia of Native American history, identity, and sacred connection. For indigenous peoples, land is not property to be owned but a living entity, a relative, imbued with spirit, memory, and an intricate web of relationships. A "Map of Native American Spiritual Sites" is therefore far more than a cartographic exercise; it is an invitation to understand a worldview, a testament to enduring resilience, and a guide to the sacred heart of a continent. This journey through such a map reveals not just locations, but stories, ceremonies, and the unbreakable bond between people and place.

Defining the Sacred Landscape

What constitutes a "spiritual site" in Native American traditions? It extends far beyond the Western concept of a church or temple. Spiritual sites are diverse and deeply integrated into the natural world. They can be ancient burial grounds, monumental earthworks, rock art panels, ceremonial circles, specific mountain peaks, rivers, lakes, caves, forests, or even unique rock formations. These places are sacred because they are where ancestral spirits reside, where creation stories unfolded, where ceremonies have been performed for generations, where healing powers manifest, or where individuals undertake vision quests to connect with the spiritual realm. Each site carries layers of meaning, often specific to a particular tribe or nation, but universally revered as places of power, memory, and profound spiritual significance. They are anchors of identity, living libraries of oral traditions, and vital centers for ongoing cultural practices.

Ancient Roots: A Continent Woven with Spirit

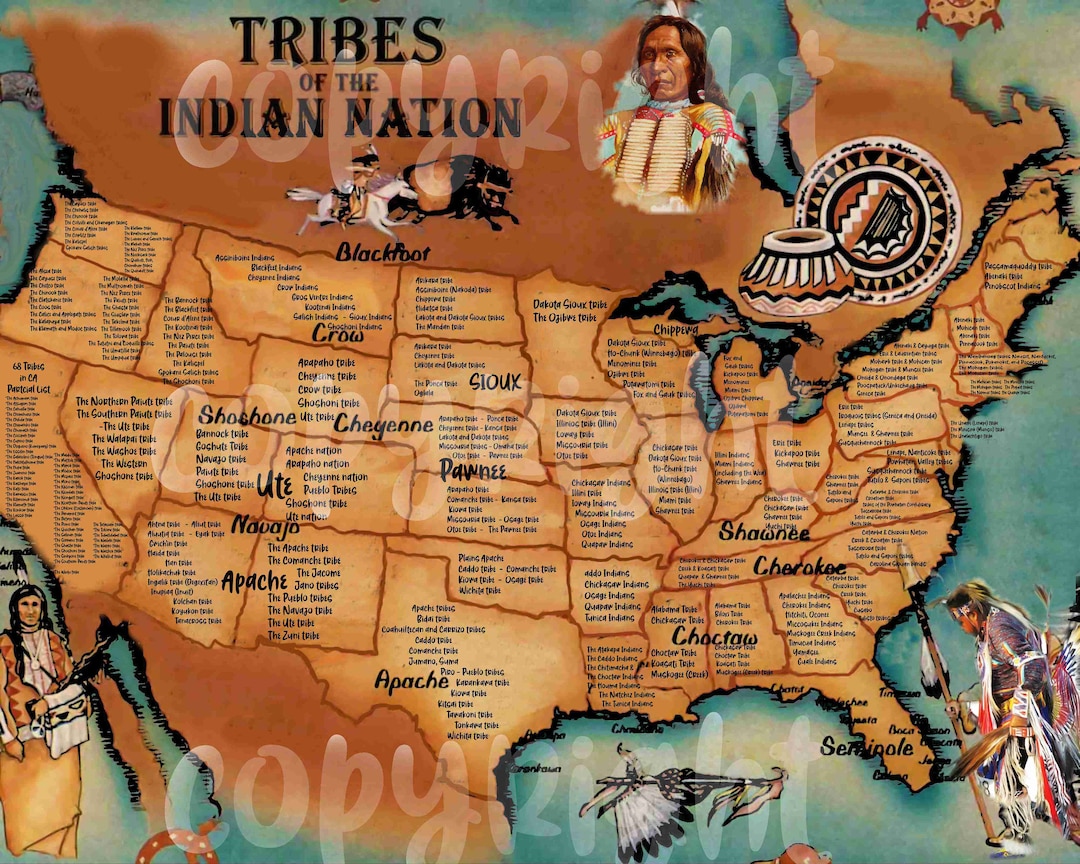

Before European colonization, the North American continent was a vibrant mosaic of hundreds of distinct Native American nations, each with its own language, culture, and spiritual traditions. Yet, a shared reverence for the land and an understanding of its inherent sacredness permeated all these diverse societies. Spiritual sites were integral to daily life, guiding movements, dictating seasonal ceremonies, and shaping social structures.

Consider the Cahokia Mounds near modern-day St. Louis, Illinois. Once the largest and most sophisticated pre-Columbian city north of Mexico, Cahokia was a bustling metropolis centered around Monks Mound, a colossal earthen pyramid. This was not just an urban center but a spiritual hub for the Mississippian culture, a place of astronomical observation, elaborate ceremonies, and a vibrant spiritual economy that influenced vast regions. Further west, the Ancestral Puebloan people constructed the intricate urban centers of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, aligning their great houses and kivas (underground ceremonial chambers) with celestial events, creating a sacred landscape that mirrored their cosmology. These sites were testaments to advanced engineering, but more importantly, to a profound spiritual understanding of their place in the universe.

In the Ohio Valley, the Great Serpent Mound, an effigy mound stretching over a quarter-mile, coils across the landscape, an enigmatic testament to the Adena and Fort Ancient cultures. Its precise astronomical alignments suggest a sophisticated understanding of the cosmos and its spiritual implications, likely used for calendrical purposes and ceremonies marking significant celestial events. These examples merely scratch the surface of a continent teeming with spiritual power, from the sacred Black Hills of the Lakota to the ancient fishing sites along the Columbia River, each a vital artery in the spiritual body of indigenous nations.

The Cataclysm of Colonization: Dispossession and Desecration

The arrival of European colonists brought an unprecedented cataclysm to Native American peoples and their sacred lands. Driven by ideologies of manifest destiny, religious zeal, and the insatiable desire for land and resources, colonial powers systematically dispossessed indigenous nations, leading to widespread violence, disease, and forced removal. This process was not merely a physical displacement; it was a spiritual assault.

Sacred sites were often desecrated, destroyed, or appropriated for colonial purposes. Burial grounds were plowed over, ceremonial sites were mined, forests cleared, and mountains developed. The very concept of land as a living, spiritual entity was alien to the European mindset, which viewed it as a commodity to be exploited or "improved." Treaties, often broken, rarely acknowledged the spiritual significance of the land. The infamous "Trail of Tears," the forced removal of the Cherokee and other Southeastern tribes, was not just a journey of physical suffering but a profound spiritual sundering from their ancestral lands, where their creation stories, ceremonies, and ancestors resided.

Later U.S. government policies, such as the reservation system and assimilation efforts, further aimed to sever Native Americans’ connection to their traditional spiritual homelands. Children were sent to boarding schools, forbidden to speak their languages or practice their ceremonies, further attempting to erase their cultural and spiritual ties to the land. Even today, many national parks and monuments, celebrated for their natural beauty, were once, and often still are, deeply sacred sites for indigenous peoples, their original caretakers forcibly removed or denied access. Places like Devils Tower (Mateo Tepee) in Wyoming, sacred to numerous Plains tribes for vision quests and ceremonies, became a tourist attraction, often without adequate respect for its spiritual significance.

Resilience and the Fight for Protection

Despite centuries of systematic oppression, Native American peoples have demonstrated extraordinary resilience in maintaining their spiritual practices and fighting for the protection and repatriation of their sacred sites. The spiritual connection to the land proved unbreakable. Hidden ceremonies continued, oral traditions were secretly passed down, and the memory of sacred places endured.

The late 20th century saw a resurgence in Native American activism and a growing awareness of indigenous rights. Landmark legislation like the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978 affirmed the right of Native Americans to practice their traditional religions and access sacred sites. However, AIRFA has often been criticized for its lack of enforcement power and its failure to prevent federal agencies from developing or otherwise impacting sacred lands. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 was another crucial step, mandating the return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated tribes. While imperfect, these acts have provided some legal framework for tribes to challenge desecration and reclaim what was lost.

The struggle continues today. Tribes are actively engaged in legal battles, protests, and educational campaigns to protect their sacred places from threats such as mining, oil and gas drilling, logging, dam construction, and unchecked tourism. The fight for Bear Butte (Noahvose) in South Dakota, a sacred site for the Lakota, Cheyenne, and other Plains tribes, continues against surrounding development. The successful return of Blue Lake to the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico in 1970 after decades of advocacy stands as a powerful testament to the enduring commitment to these sacred places. These contemporary struggles highlight that the "map" of spiritual sites is not static; it is a living document of ongoing cultural vitality and resistance.

The Map as a Guide to Understanding and Respectful Travel

For those interested in history, culture, and respectful travel, a "Map of Native American Spiritual Sites" offers an unparalleled opportunity for deeper understanding. It serves as an educational tool, challenging dominant narratives that often erase indigenous presence and contributions. By locating these sites, we begin to see the land through a different lens – not as wilderness to be conquered, but as a cultivated, spiritual landscape, carefully stewarded for millennia.

When approaching these sites, whether physically or conceptually, it is paramount to do so with humility and respect. This means:

- Seeking permission: Many sacred sites are not open to the public or require specific protocols for visitation. Respecting tribal sovereignty and customs is essential.

- Learning from indigenous voices: Prioritize information from tribal historians, elders, and cultural centers.

- Leaving no trace: Physically and spiritually. Do not disturb artifacts, rock art, or natural features.

- Understanding context: Appreciate that these are not merely historical relics but living places of ongoing spiritual practice. Avoid treating them as mere tourist attractions.

- Supporting tribal efforts: Contribute to organizations working to protect these sites and support Native American-owned businesses and cultural initiatives.

Consider a visit to Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, home to incredible Ancestral Puebloan cliff dwellings. Understanding that these were not just homes but intricate spiritual complexes, connected to the sky, earth, and underworld, transforms the experience. Similarly, exploring the spiritual significance of Mount Shasta in California for the Wintu, Karuk, and Modoc peoples, or the powerful ceremonial landscape of Canyon de Chelly for the Navajo (Diné), enriches the journey beyond mere sightseeing. These are not just points on a map; they are gateways to understanding the rich, diverse, and enduring spiritual traditions of Native America.

The Enduring Power of Place

Ultimately, the map of Native American spiritual sites is a testament to the enduring power of place in shaping identity and sustaining culture. These sites are not merely historical markers; they are living landscapes that continue to nourish the spiritual, cultural, and physical well-being of Native American peoples. They are anchors of memory, repositories of traditional ecological knowledge, and vital centers for cultural revitalization.

For those of us who share this land, understanding and respecting this sacred geography is not just an act of historical education; it is an imperative for reconciliation and a path toward a more just and interconnected future. By engaging with this spiritual map, we are invited to listen to the land, to learn from its original caretakers, and to recognize the profound and unbroken spiritual legacy that continues to resonate across the North American continent. It is a map that guides us not just through space, but through time, spirit, and the enduring heart of Native America.