Beyond the Border: Understanding Native American Sovereignty Through Maps

The land beneath our feet in North America isn’t just "America"; it’s a vast, intricate tapestry woven from millennia of Indigenous presence, governance, and profound spiritual connection. For the curious traveler and the discerning student of history, understanding this deeper landscape begins not with modern state lines, but with the complex, often contentious, and always significant maps of Native American sovereignty. These aren’t just historical curiosities; they are living documents that explain identity, ongoing struggles, and the very fabric of nation-to-nation relationships. This article will delve into the history, identity, and profound implications of Native American sovereignty issues as understood through the lens of maps, providing essential context for any journey through these ancestral lands.

The Invisible Landscape: Before the Lines Were Drawn

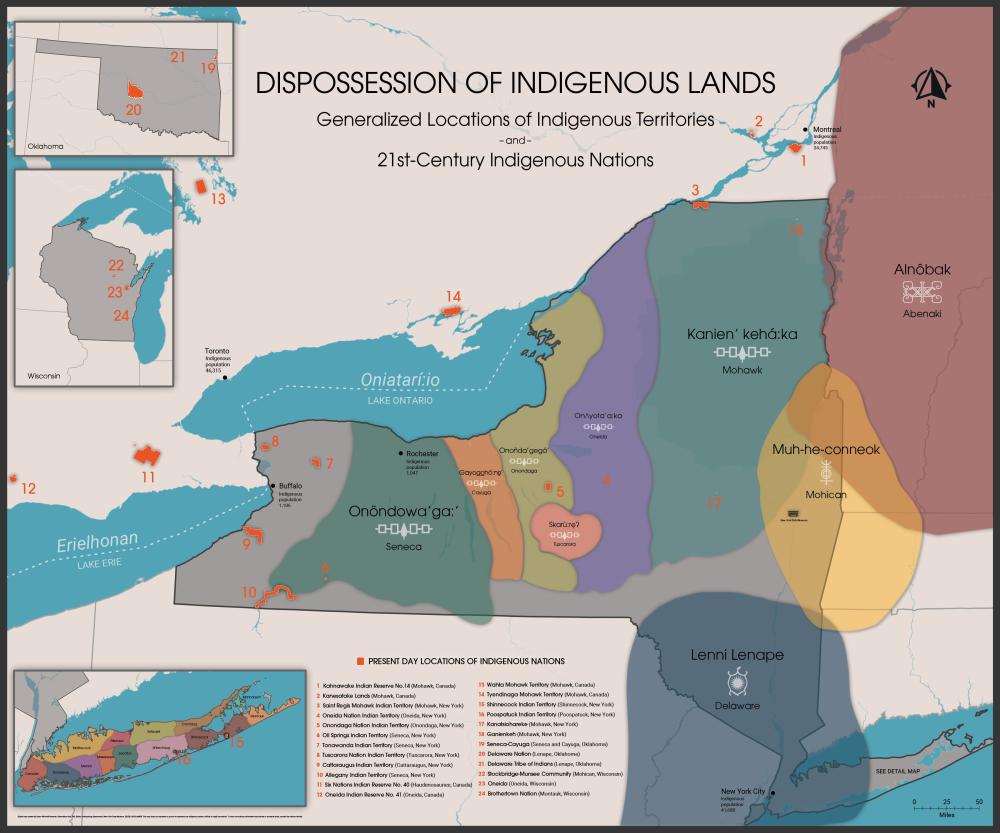

To truly grasp the concept of Native American sovereignty, we must first cast our minds back to a time before European colonization. Millions of Indigenous people inhabited the continent, organized into hundreds of distinct nations, tribes, and confederacies, each with its own sophisticated systems of governance, laws, trade networks, and cultural practices. Their "maps" weren’t always etched on paper; they were lived, remembered, and passed down through oral traditions, song, and ceremony. Boundaries were often defined by natural features – rivers, mountain ranges, distinct ecological zones – and were understood through patterns of resource use, hunting grounds, seasonal migrations, and inter-tribal agreements.

These were not empty lands awaiting discovery. They were fully formed societies with complex political geographies. The idea of absolute, exclusive land ownership in the European sense was often alien; instead, concepts of stewardship, shared resources, and usufructuary rights (the right to use and enjoy the profits and advantages of property belonging to another as long as it is not damaged or altered) prevailed. This pre-colonial understanding is foundational: it establishes that Indigenous sovereignty is inherent, predating the arrival of any colonial power. It wasn’t granted; it was, and is, an intrinsic right.

A Legacy of Lines: Treaty Maps and Their Betrayal

The arrival of European powers introduced a new era of mapping – and a new era of conflict. European colonizers, and later the United States, sought to define, acquire, and control land through treaties. For Indigenous nations, these treaties were solemn agreements between sovereign entities, outlining boundaries, rights, and responsibilities. For the U.S. government, treaties initially served as a mechanism to legitimize land cessions, allowing for westward expansion while ostensibly maintaining peace.

Early treaty maps, though often drawn by non-Native surveyors, are crucial documents. They represent the initial recognition of tribal land claims and, by extension, tribal sovereignty. When a tribe signed a treaty, they were not "giving up" their sovereignty; rather, they were exercising it, negotiating terms with another sovereign power. These maps delineate the vast territories tribes ceded to the United States, but crucially, they also show the lands tribes retained. These retained lands often formed the basis for what would become modern reservations.

However, the history of these treaties is overwhelmingly one of betrayal. As U.S. expansionist desires grew, treaties were routinely broken, reinterpreted, or simply ignored. The infamous Indian Removal Act of 1830, for example, forcibly relocated numerous Eastern Woodlands tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) from their ancestral lands to "Indian Territory" (present-day Oklahoma) along the "Trail of Tears." The maps of this period illustrate a shrinking Indigenous presence, a relentless push westward, and the violent redrawing of the continent’s human geography, often with little regard for the sovereign agreements previously made.

Eras of Erosion: Allotment, Termination, and the "Checkerboard"

The late 19th and 20th centuries saw further assaults on tribal land and sovereignty, vividly reflected in the evolving maps.

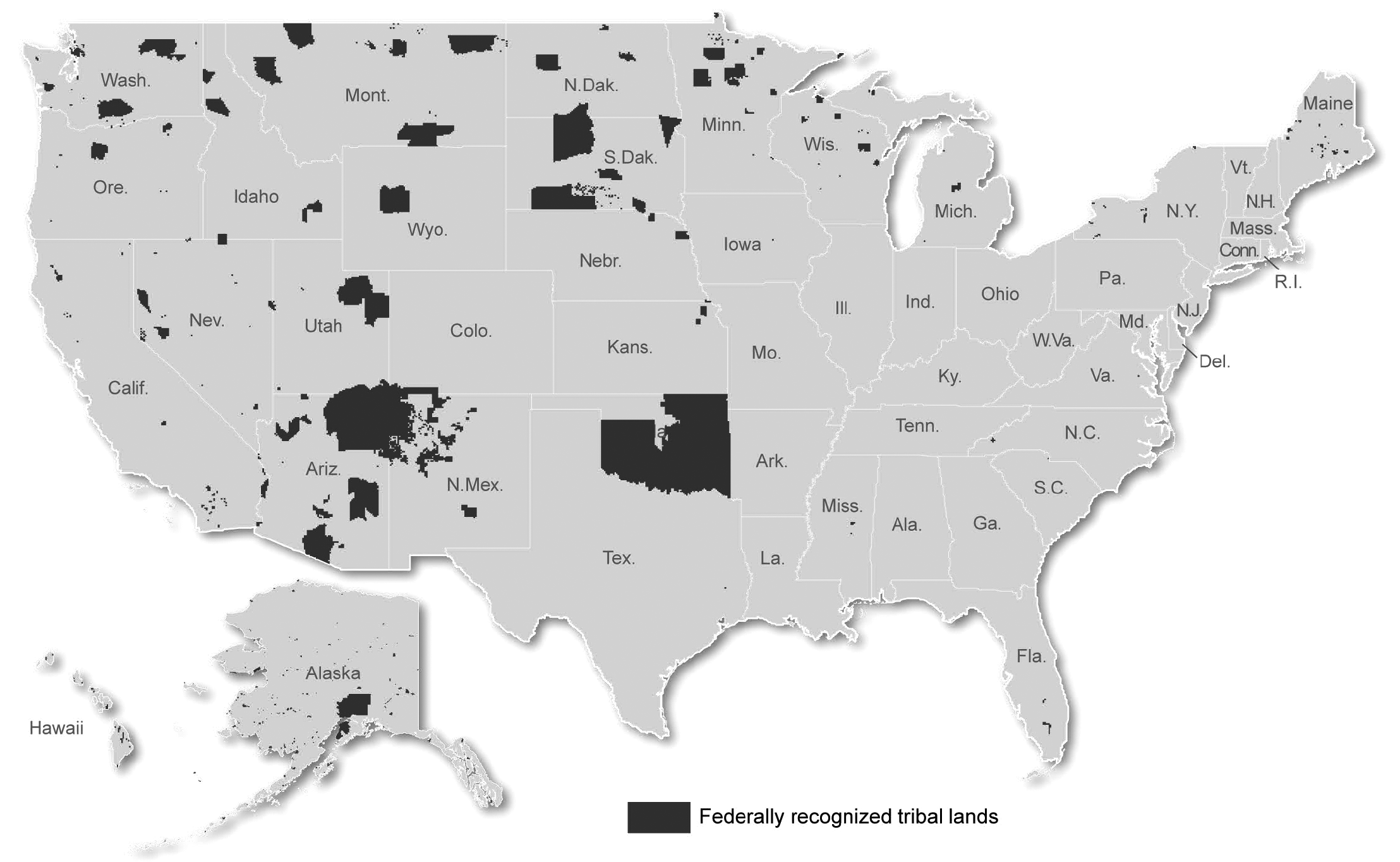

The Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) of 1887 was a particularly devastating policy. Driven by a desire to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream society and to open up more land for non-Native settlement, the Act sought to dismantle communal tribal land ownership. Reservation lands were surveyed and divided into individual plots (allotments) of 40, 80, or 160 acres, to be owned by individual Native families. Any "surplus" land, after allotments were made, was declared open for sale to non-Native settlers. The result was a massive loss of tribal land – from 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million by 1934.

The maps generated by the Dawes Act era are visually striking and illustrate a phenomenon known as the "checkerboard" ownership pattern. Within the exterior boundaries of a reservation, parcels of land might be owned by the tribe, by individual Native Americans (often held in federal trust), or by non-Native individuals or corporations. This checkerboard pattern creates immense jurisdictional complexities, making it difficult for tribal governments to exercise consistent authority over land use, taxation, and law enforcement within their own reservation boundaries. It’s a direct visual representation of fragmented sovereignty.

Decades later, the Termination Era (1950s-1960s) presented another existential threat. Federal policy aimed to "terminate" the federal government’s relationship with tribes, dissolving tribal governments, selling off remaining tribal lands, and relocating Native people to urban areas. Over 100 tribes were terminated during this period, resulting in immense poverty, cultural dislocation, and further loss of land. The maps of this period show entire tribal entities disappearing from the federal record, only to fight for decades to regain their federally recognized status.

Thankfully, the Self-Determination Era, beginning in the 1970s, marked a significant shift. Tribes began to regain control over their own affairs, assert their sovereignty, and rebuild their nations. This era has seen a resurgence in tribal land acquisition, the re-establishment of tribal governments, and renewed efforts to protect cultural heritage.

What is Tribal Sovereignty Today?

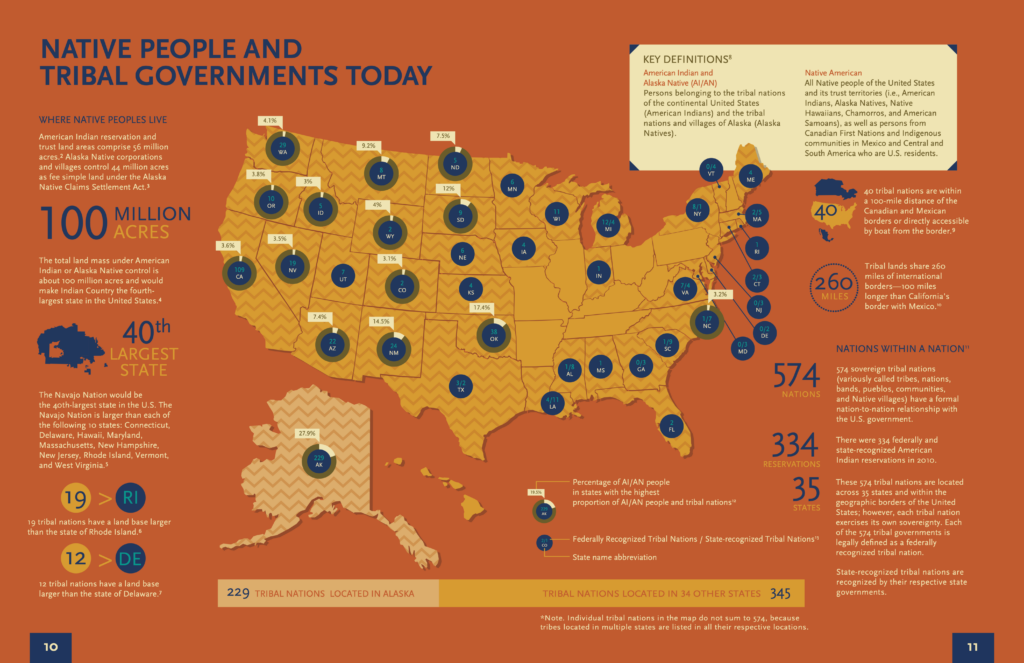

Understanding tribal sovereignty today is crucial. It is not "state sovereignty" or a "grant" from the U.S. government. Instead, tribal sovereignty is inherent, meaning it predates the United States and continues to exist. Tribes are recognized as distinct political entities, possessing the right to govern themselves. The relationship is often described as "nation-to-nation."

However, this sovereignty is also limited. The U.S. Congress holds "plenary power" over Native American affairs, meaning Congress can legislate for tribes in ways it cannot for states. This power, though controversial, has been upheld by the Supreme Court. Despite this limitation, tribes possess a wide range of governmental powers:

- Self-governance: Establishing their own forms of government (often constitutional republics, but some maintain traditional systems).

- Law enforcement and justice systems: Operating tribal police forces and tribal courts, which handle civil and, in some cases, criminal matters involving tribal members and, increasingly, non-members within their jurisdiction.

- Taxation: Imposing taxes on activities and property within their reservation boundaries, including businesses, sales, and sometimes income.

- Land use and zoning: Regulating development, environmental protection, and resource management on tribal lands.

- Economic development: Establishing businesses, casinos (where permitted), and other ventures to generate revenue for their communities.

- Natural resource management: Controlling hunting, fishing, water rights, and mineral extraction on their lands, often leading to significant legal battles with states and corporations.

Maps are absolutely vital in defining the boundaries within which these sovereign powers can be exercised. They delineate reservation borders, trust lands, fee lands, and areas of concurrent jurisdiction. The complexities arising from the checkerboard pattern mean that a crime committed by a non-Native person on fee land within a reservation, for example, might fall under state jurisdiction, while the same crime committed by a tribal member on trust land falls under tribal or federal jurisdiction. These jurisdictional mazes are a direct consequence of the historical erosion of clear, contiguous tribal lands.

Identity, Land, and Resilience

For Indigenous peoples, the connection between land, identity, and sovereignty is profound and inseparable. Land is not merely property; it is the repository of history, culture, language, and spiritual practice. Ancestral lands, even those long lost, continue to shape identity and inform claims for justice.

Maps, therefore, become powerful tools for asserting and reclaiming identity. They are used in land back movements, in legal battles for treaty rights, and in efforts to protect sacred sites and cultural resources. The fight for clean water at Standing Rock, for example, was fundamentally about tribal sovereignty, the protection of ancestral lands, and the right to manage resources vital to cultural survival, all within a geographical context defined by maps.

The resilience of Native American nations is a testament to their enduring connection to their lands and their commitment to self-determination. Despite centuries of dispossession, assimilation policies, and violence, Indigenous cultures thrive, languages are being revitalized, and tribal nations are asserting their place as vital, self-governing entities within the broader fabric of North America.

The Traveler’s Perspective: Engaging Respectfully

For travelers, understanding the maps of Native American sovereignty transforms a journey from mere sightseeing into a richer, more respectful experience. When you drive through a reservation, you are not just entering a different county or state; you are entering another nation.

- Respect Tribal Laws: Be aware that tribal nations have their own laws, which may differ from state or federal laws. Observe posted signs, respect cultural protocols, and if unsure, ask.

- Support Tribal Economies: Seek out tribally owned businesses, hotels, restaurants, and cultural centers. Your tourism dollars can directly support Indigenous communities.

- Learn and Listen: Visit tribal museums, cultural centers, and interpretative sites. Engage with tribal members if opportunities arise, and listen to their stories and perspectives.

- Be Mindful of Sacred Sites: Many areas, though seemingly natural landscapes, hold deep spiritual significance. Treat all lands with respect and adhere to any access restrictions.

- Challenge Misconceptions: Recognize that Native American communities are diverse and contemporary. Avoid perpetuating stereotypes or viewing Indigenous cultures as relics of the past.

By appreciating the complex history and ongoing reality of Native American sovereignty as depicted through maps – whether ancient ancestral territories or modern reservation boundaries – travelers gain a deeper understanding of the land, its true history, and the vibrant, living cultures that continue to shape it. It’s an invitation to look beyond the lines on a highway map and see the enduring nations that have always been here, and always will be.