Unveiling Sovereignty: A Traveler’s Guide to the Map of Native American Self-Governance

When we look at a map of the United States, our eyes are often drawn to state borders, national parks, and major cities. But beneath this familiar surface lies another, equally vital and far more complex cartography: the intricate web of Native American self-governance. This isn’t just a map of land; it’s a living document of inherent sovereignty, cultural resilience, and an ongoing journey of self-determination spanning millennia. For the curious traveler and the engaged student of history, understanding this map is key to appreciating the vibrant, diverse, and distinct nations that share this continent.

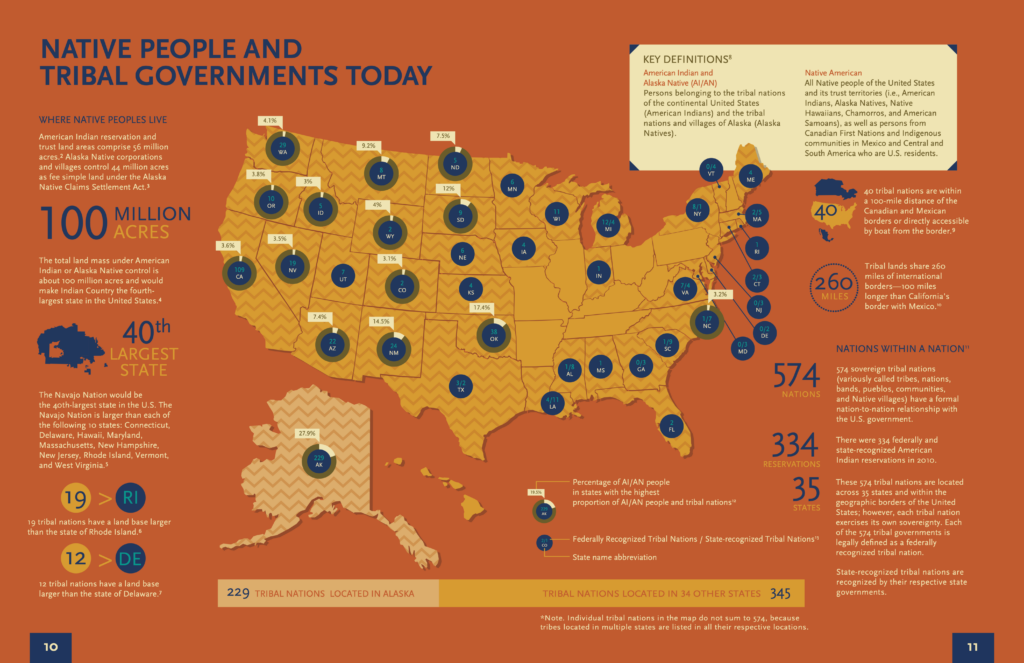

Forget the simplistic notion of "reservations." The reality is a dynamic tapestry of over 570 federally recognized tribal nations, alongside numerous state-recognized and unrecognized tribes, each with its own unique history, culture, and model of self-governance. This article will delve into the historical roots, the evolving models, and the profound identity embedded within this crucial map, offering a deeper understanding for anyone seeking to engage respectfully and knowledgeably with Indigenous peoples.

The Bedrock of Sovereignty: An Inherent Right, Not a Grant

To truly grasp the map of Native American self-governance, we must first understand the concept of tribal sovereignty. This isn’t a privilege granted by the United States government; it is an inherent right that predates the formation of the U.S. and continues to exist. Before European contact, North America was a continent of hundreds of distinct, self-governing nations, each with its own political systems, economies, languages, and cultures.

When European powers arrived, they engaged with these Indigenous nations as sovereign entities, often through treaties. While these treaties were frequently violated, coerced, or misinterpreted, their very existence affirmed the status of Indigenous peoples as independent nations capable of negotiating international agreements. The U.S. Constitution itself acknowledges treaties as the supreme law of the land, implicitly recognizing the original sovereignty of tribal nations.

The landmark Supreme Court cases of the 1830s, particularly Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia, further defined this unique status. Chief Justice John Marshall described tribal nations as "domestic dependent nations," a term that acknowledged their distinct governmental authority while placing them within the geopolitical boundaries of the U.S. This complex legal status forms the bedrock upon which all modern self-governance models are built. Tribal governments exercise powers similar to state or federal governments, including the ability to form their own governments, enact laws, establish court systems, levy taxes, regulate commerce, control membership, and manage natural resources within their territories.

A Historical Odyssey: Shaping the Modern Map

The current map of self-governance is not static; it’s a product of centuries of policy shifts, resistance, and resilience.

Pre-Contact (Before 1492): The map was defined by vast territories of independent nations, from the Iroquois Confederacy in the Northeast to the Pueblo Nations in the Southwest, the expansive plains of the Lakota, and the complex societies of the Pacific Northwest. Each had well-defined political structures and traditional land use.

Colonial and Early U.S. Eras (1500s-1830s): European colonization brought devastating disease, warfare, and land encroachment. Treaties became tools for land cession, often under duress. The map began to shrink Indigenous territories, consolidating them into smaller "reserves" or "reservations," a term originally denoting land "reserved" by tribes, not "given" to them.

Removal Era (1830s-1850s): Driven by land hunger and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, the U.S. forcibly removed many Eastern Woodland tribes to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) via the "Trail of Tears." This dramatically redrew the map, creating concentrated tribal lands in the west.

Allotment and Assimilation Era (1887-1934): The Dawes Act of 1887 was a catastrophic attempt to dismantle tribal land bases and assimilate Indigenous peoples. Communal tribal lands were broken up into individual allotments, with "surplus" land sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy drastically fragmented tribal landholdings, often creating a checkerboard pattern of Native and non-Native ownership within reservation boundaries, a legacy still visible on the map today. Boarding schools simultaneously attacked Indigenous languages and cultures.

Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) Era (1934-1950s): Acknowledging the failures of allotment, the IRA sought to reverse the trend of assimilation by encouraging tribes to reorganize their governments and re-establish land bases. Many tribes adopted written constitutions and elected councils under the IRA, though not all tribes chose to do so, fearing continued federal oversight. This period saw a strengthening of tribal governmental structures.

Termination Era (1950s-1960s): This short-sighted and disastrous policy aimed to "terminate" the federal government’s relationship with tribes, ending their sovereign status and trust protections. Over 100 tribes were terminated, leading to severe poverty, loss of land, and cultural disruption. This period left deep scars on the map and tribal communities, with some terminated tribes still fighting for restoration.

Self-Determination Era (1970s-Present): The civil rights movement and growing Indigenous activism led to a monumental shift. The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975 allowed tribes to take over federal programs and services previously administered by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). This empowered tribes to manage their own healthcare, education, social services, and economic development, leading to a revitalization of tribal governance and a more robust exercise of sovereignty. This era profoundly shaped the modern map, as tribes began to assert greater control over their territories and destinies.

Unpacking the Map: Models of Self-Governance Today

The map today is a complex mosaic, reflecting these historical shifts and the unique circumstances of each nation.

-

Federally Recognized Tribes:

- The Majority: These 574 nations (as of 2023) maintain a direct, government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government. Their lands are often held in "trust" by the U.S., meaning the federal government holds legal title, but the beneficial ownership and use are by the tribe. This trust relationship is a critical aspect of federal Indian law.

- Powers: Federally recognized tribes exercise broad governmental powers over their members and lands. This includes establishing their own judicial systems (tribal courts), maintaining law enforcement (tribal police), regulating land use and zoning, managing natural resources, operating schools, healthcare facilities, and developing their own economies (including casinos, tourism, energy production, and agriculture).

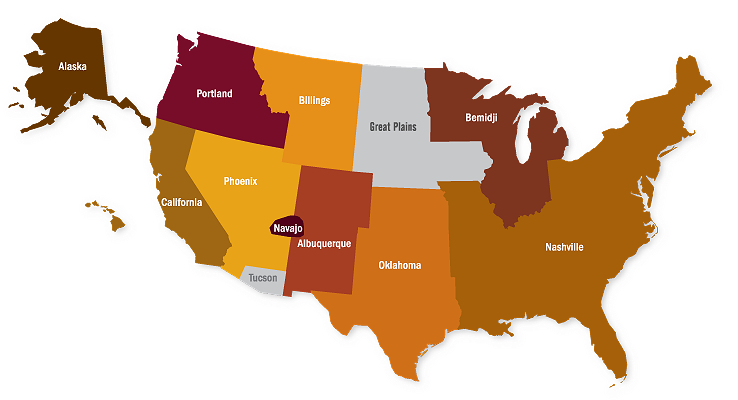

- Geographic Distribution: These tribes are found across the contiguous U.S. and Alaska, often on reservations or trust lands. The boundaries on the map denote areas of tribal jurisdiction, though land ownership within these boundaries can be mixed due to the legacy of allotment.

-

State-Recognized Tribes:

- Unique Status: Some tribes are recognized by individual states but do not have federal recognition. There are over 60 such tribes in states like California, New York, Virginia, and Massachusetts.

- Powers and Challenges: Their powers and benefits vary significantly by state. They may receive some state funding, cultural preservation support, or limited jurisdiction. However, they lack the federal protections, funding, and the direct government-to-government relationship with the U.S. that federally recognized tribes possess. Their status on the map is less clearly defined by federal boundaries and more by state legislative acts.

-

Unrecognized and Petitioning Tribes:

- The Fight for Recognition: Many Indigenous communities exist that are neither federally nor state-recognized. Some are historically documented tribes that lost their status due to termination, administrative errors, or simply never having a formal relationship with the U.S. government. Others are petitioning the federal government for recognition, a lengthy, costly, and often politically charged process.

- Identity Without Status: These communities maintain their cultural identity, traditions, and self-governance structures, but they lack the legal and financial benefits that come with recognition. Their presence on the map is often invisible in official government renderings, yet their identity and historical claims remain strong.

-

Alaska Native Villages and Corporations:

- A Distinct Model: Alaska has a unique model shaped by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) of 1971. Instead of creating reservations, ANCSA established 12 regional and over 200 village corporations, which received land and financial settlements in exchange for extinguishing aboriginal land claims. These corporations are for-profit entities that manage resources and provide economic benefits.

- Dual Governance: Alongside these corporations, many Alaska Native villages continue to operate as federally recognized tribal governments, exercising governmental functions. The map of Alaska thus shows a complex interplay between corporate land ownership and tribal governmental jurisdiction.

Identity, Culture, and Resilience: The Soul of the Map

Beyond the legal and political structures, the map of Native American self-governance is fundamentally about identity and culture. Each dot, each shaded area, represents a living community dedicated to preserving its unique heritage.

- Language Revitalization: Self-governance allows tribes to establish immersion schools, develop language programs, and fund efforts to bring back endangered Indigenous languages, which are intrinsically linked to cultural identity and worldview.

- Cultural Preservation: Tribal governments support traditional arts, ceremonies, storytelling, and historical sites, ensuring that ancient practices endure and evolve for future generations.

- Economic Self-Sufficiency: The ability to govern their own economies, whether through gaming, tourism, resource management, or other enterprises, provides the resources necessary to fund tribal programs and reduce dependency on federal aid. This economic sovereignty is vital for self-determination.

- Environmental Stewardship: Many tribes prioritize traditional ecological knowledge and sustainable practices, acting as guardians of their ancestral lands and waters. Their self-governance allows them to implement environmental regulations and conservation efforts that reflect their deep connection to the land.

- Health and Education: Taking control of healthcare and education systems allows tribes to address historical disparities and tailor services to meet the specific needs and cultural contexts of their communities, promoting holistic well-being.

The map, therefore, is not just a collection of administrative boundaries; it is a testament to the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples. It signifies the right to define oneself, to practice one’s culture, to speak one’s language, and to determine one’s future. It represents a continuous journey of rebuilding and strengthening nations after centuries of profound challenges.

For the Traveler and Learner: Engaging Respectfully

For those drawn to explore the rich history and vibrant cultures of Native America, understanding this map is paramount.

- Acknowledge Sovereignty: When visiting tribal lands, remember you are entering another nation. Respect their laws, customs, and governance.

- Research Before You Go: Learn about the specific tribe whose land you are visiting. Understand their history, their current governmental structure, and their cultural protocols.

- Support Tribal Economies: Purchase goods from Native-owned businesses, visit tribal museums and cultural centers, and consider staying at tribally owned hotels. Your dollars directly support self-determination.

- Be a Respectful Guest: Ask for permission before photographing individuals, respect sacred sites, and be mindful of local etiquette.

- Educate Yourself Continually: The story of Native American self-governance is dynamic. Engage with contemporary Indigenous voices, read Native authors, and listen to Indigenous perspectives.

The map of Native American self-governance is an invitation to look deeper, to challenge preconceived notions, and to recognize the profound and enduring presence of Indigenous nations within the modern landscape of North America. It tells a story of survival, adaptation, and an unwavering commitment to identity that enriches the entire continent. By engaging with this map, we not only learn history; we participate in its ongoing unfolding.