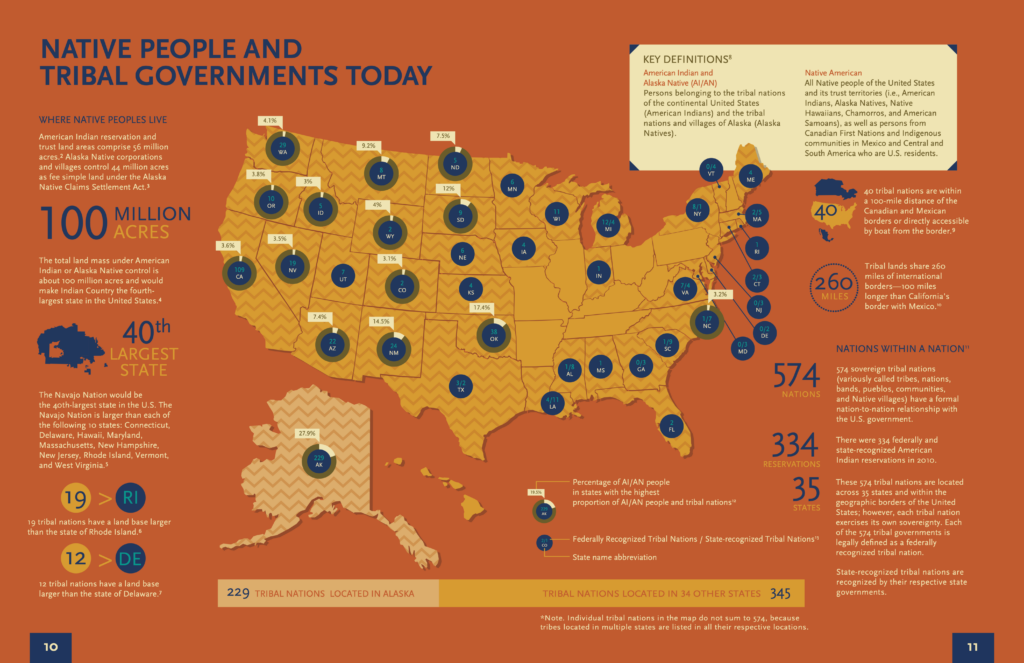

The Map of Native American Self-Determination Era is not a static atlas of ancient history; it is a dynamic, living document reflecting a profound shift in U.S. federal policy and an ongoing testament to the resilience and sovereignty of Indigenous nations. Far from merely delineating reservation borders, this map embodies centuries of struggle, the strategic reclamation of inherent rights, and the vibrant, evolving identities of over 574 federally recognized tribes within the United States. For anyone interested in American history, cultural identity, or responsible travel, understanding this map is essential.

From Dispossession to the Dawn of Self-Determination: A Necessary Historical Context

To truly grasp the significance of the self-determination map, one must first understand the historical trajectory that preceded it. For centuries, U.S. policy towards Native American tribes was characterized by a series of devastating, often genocidal, approaches:

- Removal (Early 19th Century): Policies like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 forcibly relocated eastern tribes to lands west of the Mississippi, epitomized by the Trail of Tears. This era established the concept of "Indian Territory" but also laid the groundwork for broken treaties and further land loss.

- Reservations and Assimilation (Mid-19th to Early 20th Century): As westward expansion continued, tribes were confined to increasingly smaller, often undesirable, reservation lands. The Dawes Act (General Allotment Act) of 1887 fragmented communal tribal lands into individual parcels, with the "surplus" sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy aimed to destroy tribal structures, assimilate Native peoples into mainstream American society, and further erode their land base and cultural identity. Boarding schools, where Native children were forcibly removed from their families and forbidden to speak their languages or practice their cultures, were a cruel extension of this assimilationist agenda.

- The Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) and its Limitations (1934): A brief departure from the assimilationist policies, the IRA sought to reverse some of the damage of allotment, encourage tribal self-governance, and promote economic development. While it allowed many tribes to reconstitute their governments, it was often criticized for imposing a one-size-fits-all model of governance (based on Western democratic structures) that didn’t always align with traditional tribal systems.

- Termination and Relocation (1950s-1960s): The nadir of this assimilationist policy arrived with the "Termination Era." Driven by the belief that Native Americans should be fully integrated into American society, Congress passed resolutions and acts aimed at ending the federal government’s trust relationship with tribes, liquidating tribal assets, and abolishing tribal sovereignty. Over 100 tribes were "terminated," losing their federal recognition, lands, and services. Simultaneously, the Relocation Program encouraged Native Americans to move to urban centers, promising jobs and opportunities but often leading to further cultural dislocation and poverty.

This brutal history of land theft, cultural suppression, and policy reversals left Native American communities devastated, yet their inherent sovereignty and cultural identities persisted. It was against this backdrop of profound injustice that the self-determination era began to emerge.

The Turning Tide: The Era of Self-Determination

The shift towards self-determination was not a sudden act but the culmination of decades of Native American activism, legal challenges, and a gradual recognition by some federal policymakers that past approaches had failed catastrophically. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s provided a powerful template and impetus for Native Americans to assert their rights more forcefully.

Key milestones that shaped the "Map of Native American Self-Determination Era" include:

- Growing Activism (1960s-1970s): Groups like the American Indian Movement (AIM) emerged, using direct action and protests (e.g., the occupation of Alcatraz, Wounded Knee) to draw national attention to treaty violations, poverty, and systemic discrimination.

- President Nixon’s Special Message to Congress (1970): Often cited as the official turning point, President Richard Nixon rejected the termination policy and declared a new federal policy of "self-determination without termination." He called for strengthening tribal governments and providing them with greater control over their own affairs.

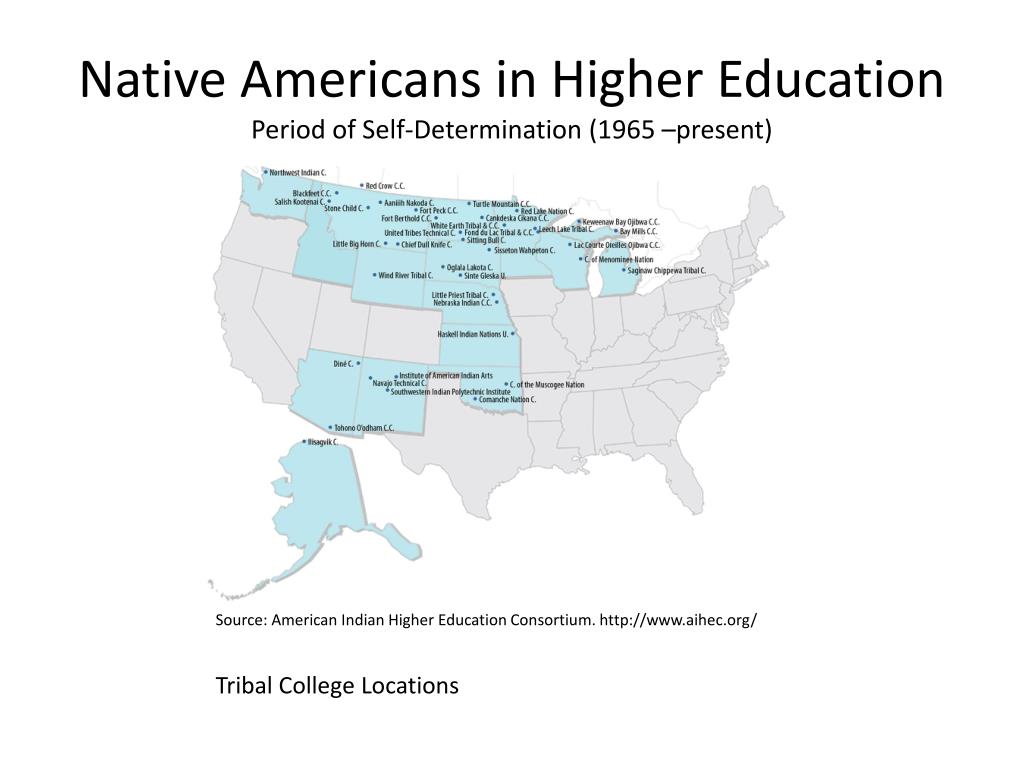

- The Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (ISDEAA) of 1975: This landmark legislation is the cornerstone of the self-determination era. It authorized federal agencies (like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service) to enter into contracts with tribal governments, allowing tribes to administer and manage their own programs and services previously run by the federal government. This was a monumental step towards empowering tribes to control their own destinies, from healthcare and education to law enforcement and resource management.

- Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) of 1978: Responding to the alarming rate of Native American children being removed from their homes and placed in non-Native foster or adoptive families, ICWA established federal standards to protect the best interests of Native children and promote the stability and security of Native families and tribes.

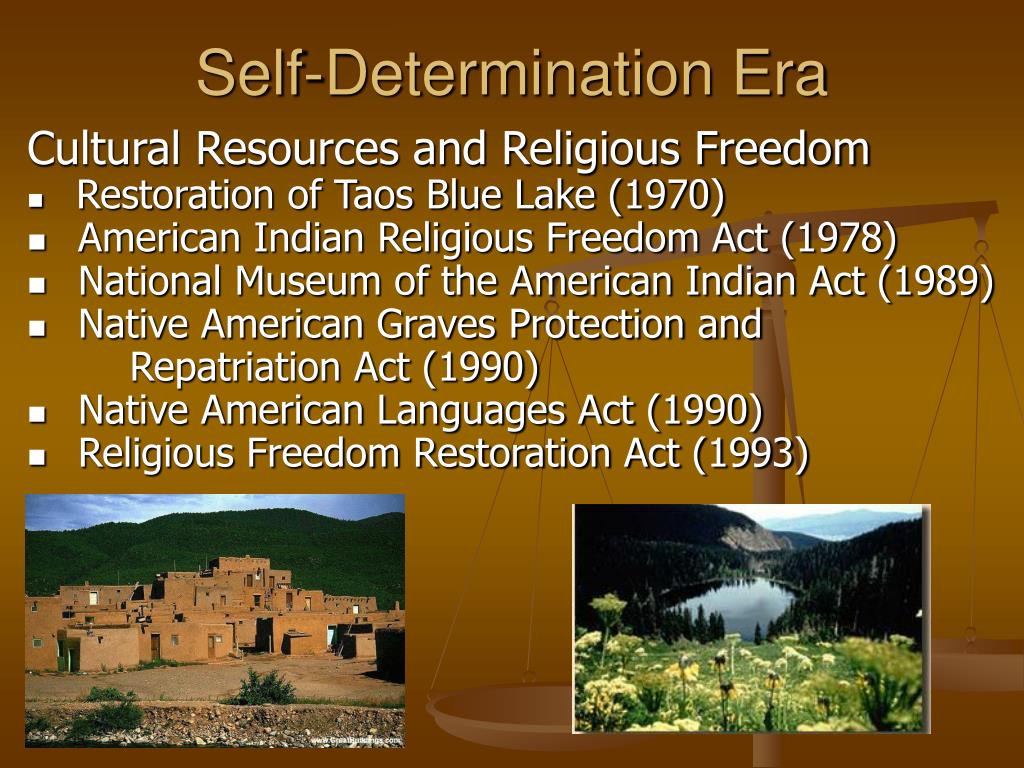

- American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978: This act sought to protect and preserve the inherent right of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and Native Hawaiians to believe, express, and practice their traditional religions.

- Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) of 1988: This act established the regulatory framework for tribal gaming, which has become a significant source of economic development and revenue for many tribes, funding essential services and infrastructure projects on reservations.

- Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990: NAGPRA requires federal agencies and museums to return Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to lineal descendants and culturally affiliated Native American tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations. This act is crucial for cultural healing and identity reclamation.

What the Map Reveals: A Layered Tapestry of Sovereignty and Identity

The "Map of Native American Self-Determination Era" is not a single, static document but rather an evolving conceptual framework that overlays traditional geographic maps with layers of legal, cultural, and historical information. It reveals:

- Federally Recognized Reservations and Trust Lands: These are the most visible components. While often depicted as fixed boundaries, these lands represent sovereign territories where tribal governments exercise jurisdiction. Under self-determination, tribes have greater control over land use, environmental regulations, resource development, and infrastructure. The map shows their geographical distribution, varying sizes, and proximity to non-Native communities, highlighting the checkerboard patterns created by allotment.

- Treaty Rights Areas: Beyond reservation borders, the map illustrates vast areas where tribes retain treaty-guaranteed rights to hunt, fish, gather, and access sacred sites. These "off-reservation" rights are crucial for cultural practices, subsistence, and economic well-being, often leading to complex co-management agreements with state and federal agencies (e.g., fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest, hunting rights in the Great Lakes region). These areas demonstrate that tribal sovereignty extends beyond physical land borders.

- Ceded Lands and Aboriginal Title Claims: The map implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) points to the immense territories historically occupied by tribes before colonization – their aboriginal lands. While most of these lands were taken through force or often fraudulent treaties, the concept of aboriginal title remains a powerful legal and moral claim. Ongoing land back movements and efforts to reclaim or co-manage ancestral lands are central to the self-determination era, even if these lands are not currently "owned" by tribes.

- Tribal Governments and Jurisdictions: The map signifies the presence of distinct governmental structures. Each recognized tribe operates as a sovereign nation with its own constitution or governing documents, judicial systems, law enforcement, and regulatory bodies. The map is a visual representation of this intricate web of inter-governmental relationships between tribes, states, and the federal government.

- Economic Development Zones: Thanks to ISDEAA and IGRA, many tribes have developed robust economies, from gaming and tourism to energy production and agriculture. These economic ventures are often located on or adjacent to reservation lands, providing jobs, services, and self-sufficiency that were unimaginable during earlier eras of federal control. The map shows these hubs of economic activity, demonstrating a shift from dependence to self-reliance.

- Cultural Revitalization Zones: While not always marked with distinct lines, the map implicitly highlights areas of intense cultural revitalization. Language immersion schools, cultural centers, traditional arts programs, and spiritual ceremonies are thriving on reservations and in urban Native communities. These efforts are direct outcomes of self-determination, as tribes regain control over their educational systems and cultural institutions, rebuilding identities systematically targeted for destruction.

- Environmental Stewardship and Resource Management: Many tribes are at the forefront of environmental protection, applying traditional ecological knowledge to manage their lands and resources. The map shows tribal parks, conservation areas, and regions where tribes are asserting their rights to clean water, air, and healthy ecosystems, often in opposition to corporate interests. This reflects a deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land that is being reasserted through self-governance.

Historical Significance and Identity: Reclaiming the Narrative

The self-determination map is profoundly significant because it illustrates a fundamental shift in power and narrative. It moves away from the colonial idea of Native Americans as vanishing peoples or wards of the state, instead affirming their status as enduring, sovereign nations.

- Reaffirmation of Sovereignty: The map visually underscores that tribal nations are not merely ethnic groups but distinct political entities with inherent rights to govern themselves. This is central to Native American identity, which is deeply rooted in nationhood, shared history, and cultural continuity.

- Cultural Resurgence: With greater control over their own affairs, tribes have been able to reverse decades of forced assimilation. Language revitalization, the practice of traditional ceremonies, the revival of ancestral arts, and the repatriation of sacred objects have breathed new life into Indigenous cultures, strengthening individual and collective identities.

- Economic Empowerment: The ability to generate and control their own revenues has allowed tribes to invest in their communities, providing housing, healthcare, education, and infrastructure that were historically neglected by the federal government. This economic sovereignty is directly tied to the ability to preserve cultural identity and improve quality of life.

- Legal and Political Agency: The self-determination era has seen tribes become powerful advocates for their own rights in federal courts and legislative bodies. This legal and political agency is a crucial component of their identity as resilient and self-governing peoples.

- Land and Identity: For Native Americans, land is not just property; it is fundamental to identity, spirituality, and cultural survival. The map’s depiction of reservations, treaty areas, and ancestral lands visually reinforces this inextricable link, highlighting the ongoing struggle and triumph of maintaining connection to place.

For the Traveler and Educator: A Guide to Respectful Engagement

For travelers and educators, the Map of Native American Self-Determination Era is an indispensable guide. It compels us to look beyond state lines and recognize the complex tapestry of Indigenous nations that coexist within the United States.

- Challenging Stereotypes: Understanding this map helps dismantle outdated and harmful stereotypes of Native Americans as relics of the past. It reveals vibrant, contemporary societies engaged in nation-building, cultural innovation, and economic development.

- Informed Travel: When planning a trip, consult tribal maps and resources. Recognize that visiting a reservation is akin to visiting a foreign nation – respect local laws, customs, and protocols. Support tribal businesses, artists, and cultural centers directly. Seek out opportunities to learn from tribal members about their history, culture, and current challenges.

- Responsible Tourism: Engage in ethical tourism that benefits tribal communities. Avoid exploiting cultural practices or sacred sites. Always ask for permission before photographing individuals or participating in ceremonies.

- Educational Imperative: For educators, this map provides a powerful tool for teaching accurate, nuanced, and respectful Native American history. It moves beyond the "first Thanksgiving" narrative to encompass the full sweep of Indigenous resilience, sovereignty, and ongoing contributions to American society. It encourages critical thinking about federal policy, treaty obligations, and the ongoing struggle for justice.

- Acknowledging Contemporary Issues: The map also serves as a reminder of ongoing challenges, such as land disputes, environmental justice issues, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis, and the fight for full recognition and funding of treaty obligations.

In conclusion, the Map of Native American Self-Determination Era is more than just geography; it is a profound narrative etched onto the land. It represents the triumph of Indigenous resilience over centuries of oppression, the strategic reassertion of inherent sovereignty, and the vibrant, ongoing evolution of diverse cultural identities. For anyone seeking a deeper understanding of America’s past, present, and future, this map is not merely a guide but a call to acknowledge, respect, and engage with the enduring nations that continue to shape this continent.