The map detailing Native American schools is far more than a simple cartographic representation; it is a profound historical document, a testament to resilience, and a living narrative of identity. Examining this map, one traces not just geographic locations, but the brutal arc of federal policy, the devastating impact of forced assimilation, and the triumphant resurgence of Indigenous self-determination. It lays bare a complex, often painful, relationship between education, power, and cultural survival, offering an invaluable lens for any traveler seeking a deeper understanding of American history, and for any educator aiming to present a more complete picture of the nation’s past and present.

Before the arrival of European colonizers, Indigenous communities across North America possessed sophisticated, localized, and highly effective educational systems. These systems were deeply integrated into daily life, transmitting cultural knowledge, spiritual beliefs, practical skills, and ethical frameworks from elders to youth. Education was experiential, communal, and directly relevant to the survival and flourishing of the tribe. Children learned through observation, storytelling, ceremony, and direct participation in hunting, gathering, crafting, and governance. There were no "schools" in the Western sense, but rather entire communities functioned as immersive learning environments, fostering strong identities rooted in land, language, and ancestral traditions. This rich tapestry of Indigenous pedagogy, however, was systematically dismantled by the colonizing powers, paving the way for the institutions that would later populate the map.

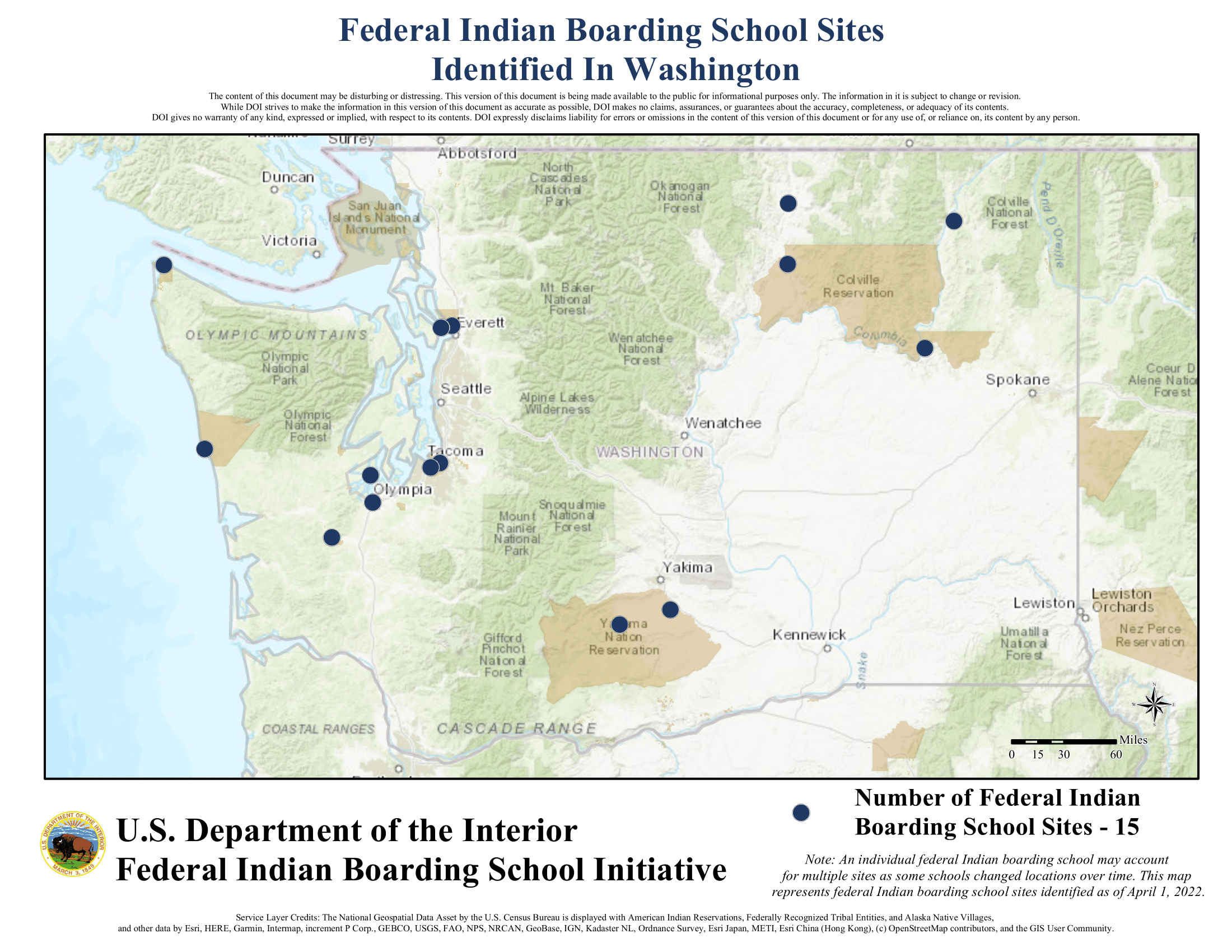

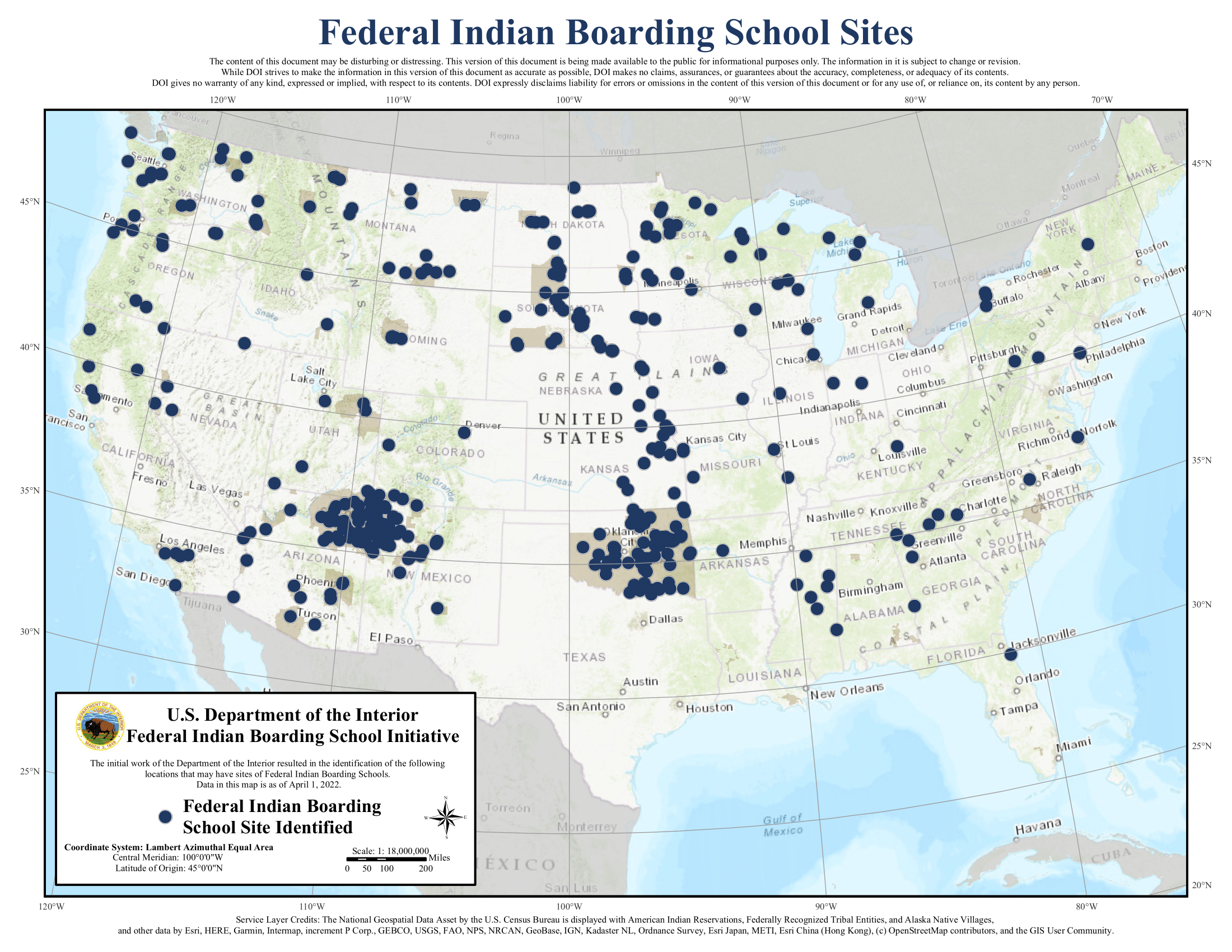

The earliest instances of formal education for Native Americans, often initiated by missionaries, were thinly veiled attempts at conversion and acculturation. But it was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that the map truly began to be etched with institutions designed explicitly to "civilize" and assimilate Indigenous children. This era saw the rise of the notorious Indian boarding school system, a cornerstone of federal policy encapsulated by Captain Richard Henry Pratt’s infamous dictum, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." The map from this period is a stark visual representation of this policy, showing a proliferation of boarding schools often located hundreds, if not thousands, of miles from tribal homelands. Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, founded by Pratt, served as the blueprint, inspiring dozens more across the country, from Chemawa in Oregon to Chilocco in Oklahoma, and countless others in between.

These schools were instruments of cultural genocide. Children, some as young as five, were forcibly removed from their families, often against the desperate pleas of their parents. Upon arrival, their traditional clothing was replaced with uniforms, their long hair was cut, and their Indigenous names were replaced with Anglo-American ones. The map’s dots represent not just buildings, but sites where languages were forbidden, and children were punished, sometimes severely, for speaking their native tongues. Spiritual practices were suppressed, traditional family bonds were severed, and a Euro-American curriculum, often focusing on manual labor for boys and domestic skills for girls, replaced Indigenous ways of knowing. The intent was clear: to erase their Indigenous identity and mold them into compliant, low-wage laborers for the dominant society.

The map, therefore, is also a ledger of trauma. The dots mark locations where children suffered physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. They signify places where disease, rampant due to overcrowding and poor sanitation, claimed countless young lives, often buried in unmarked graves on school grounds. For generations, these schools instilled deep-seated shame in Native Americans about their heritage, disrupted family structures, and created a profound sense of alienation that reverberates through communities to this day. The geographical distance between the schools and reservations underscored the policy of severing ties to land, culture, and community. The map visually demonstrates the federal government’s concerted effort to scatter and atomize Native populations, making cultural cohesion and resistance more difficult.

Despite this systematic assault, the map also implicitly tells a story of incredible resilience. While the boarding school era aimed to eradicate Indigenous cultures, it paradoxically also forged new forms of Native identity and solidarity. Students from different tribes, forced together, sometimes found common ground in their shared experiences of oppression, fostering a pan-Indian consciousness. They adapted, resisted in subtle and overt ways, and carried fragments of their traditions forward, often in secret. The enduring strength of Native American languages, ceremonies, and worldviews, despite decades of suppression, is a testament to this indomitable spirit.

The mid-20th century marked a gradual, though often slow and difficult, shift in federal Indian policy, moving away from forced assimilation towards self-determination. This pivotal change began to redraw the map of Native American education. The 1960s and 70s saw a growing movement for tribal control over education, culminating in landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This act allowed tribes to contract with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to operate their own schools and programs, recognizing their right to determine their own educational futures.

This shift dramatically altered the map, leading to the emergence and proliferation of Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs). Unlike the boarding schools, which were imposed from the outside, TCUs were born from within Native communities, reflecting their specific needs, values, and aspirations. The dots on the map representing TCUs are typically located on or near reservations, emphasizing their deep connection to the communities they serve. From Navajo Technical University to Salish Kootenai College, there are now over 30 TCUs across the United States, each a beacon of Indigenous empowerment.

These modern institutions represent a profound reclamation of education. Their curricula are uniquely designed to blend rigorous academic standards with Indigenous knowledge systems, language revitalization efforts, and cultural preservation. Students at TCUs not only pursue degrees in conventional fields like nursing, business, or engineering but also engage in studies specific to their tribal heritage, such as Native American languages, traditional ecological knowledge, tribal governance, and Indigenous arts. The map of TCUs, therefore, illustrates a vibrant network of institutions dedicated to strengthening tribal sovereignty, fostering economic development within Native communities, and ensuring the continuity of Indigenous cultures for future generations. They are crucial for addressing the generational trauma inflicted by the boarding school era, providing a culturally relevant and supportive learning environment that affirms Native identity rather than suppressing it.

For a traveler or an educator, viewing a map of Native American schools becomes an immersive historical journey. It is a visual representation of policy shifts, ideological battles, and the human cost of cultural subjugation. The contrast between the scattered, often remote locations of the assimilationist boarding schools and the community-integrated sites of TCUs tells a powerful story of oppression, survival, and resurgence. It highlights the profound shift from an education designed to eradicate identity to one dedicated to its revitalization and flourishing. The map compels us to ask critical questions: Whose history is being told? What are the consequences of educational policies on identity? And how can education be a tool for healing, empowerment, and cultural continuity?

Understanding this map is essential for comprehending the ongoing struggles and triumphs of Native American communities. It underscores the critical role of education in shaping and affirming identity. From the forced re-education of the past to the self-determined cultural affirmation of today, the journey of Indigenous education is one of relentless perseverance. Contemporary challenges remain, including chronic underfunding for TCUs and K-12 tribal schools, and the continued work of addressing the intergenerational trauma stemming from the boarding school era. Yet, the map’s current configuration, dotted with vibrant TCUs and tribal schools, signifies a future where Indigenous languages are revitalized, traditional knowledge is revered, and Native youth are empowered to define their own identities on their own terms.

The map of Native American schools is not a static artifact; it is a dynamic, evolving canvas. It invites us to move beyond superficial narratives and engage with the rich, complex history of Indigenous peoples. It challenges us to acknowledge the dark chapters of the past while celebrating the extraordinary resilience and ongoing cultural revitalization that defines Native America today. For anyone interested in American history, cultural identity, or the transformative power of education, this map serves as an indispensable guide, urging a deeper exploration into the stories of survival, adaptation, and unwavering cultural pride that continue to shape the Indigenous nations of this continent.