The Unseen Landscape: Mapping Native American Sacred Sites for Protection, History, and Identity

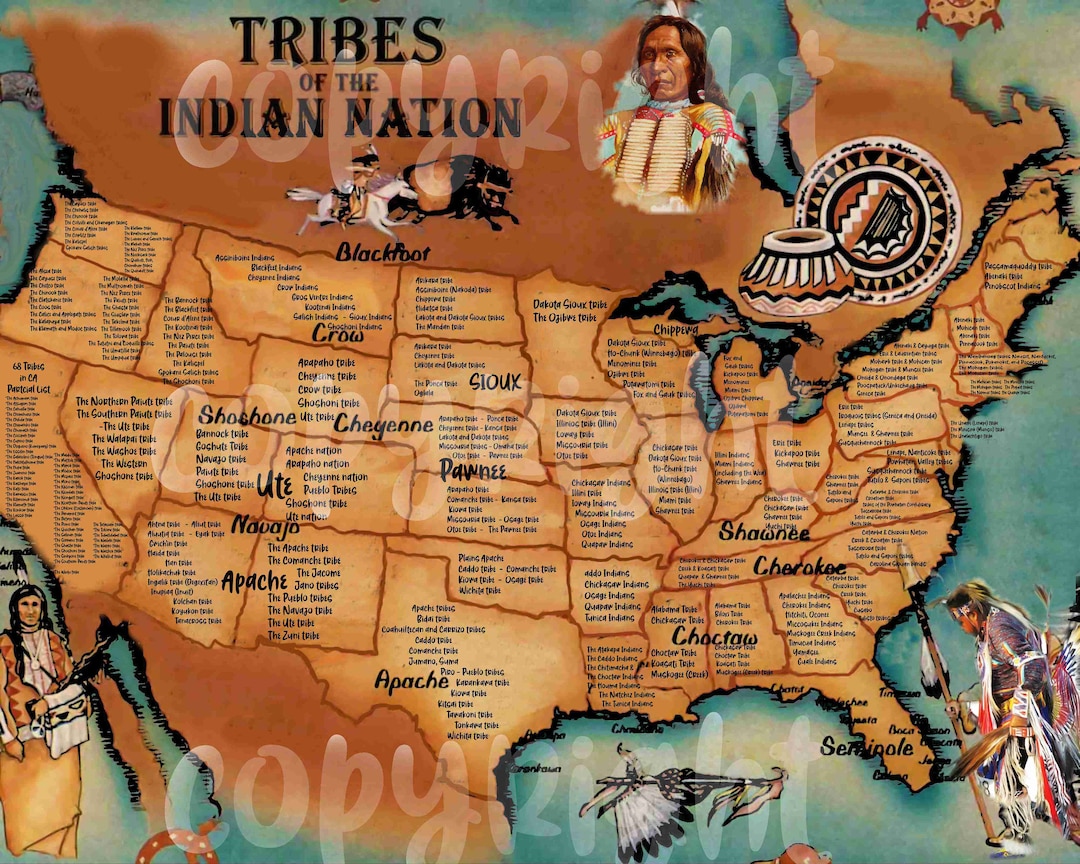

For millennia, the vast and varied landscapes of North America have been more than just terrain to its Indigenous peoples. They are living archives, spiritual anchors, and the very embodiment of identity. Every mountain, river, forest, and desert holds stories, ceremonies, and ancestral memories, marking them as sacred sites. Yet, for centuries, these places have faced existential threats, from colonial appropriation to modern industrial development. A map of Native American sacred site protection is not merely a geographical tool; it is a profound statement of resilience, a historical document, and a vital instrument in the ongoing fight to preserve Indigenous cultures and identities. This article delves into the critical role such a map plays, intertwining the historical context of dispossession with the contemporary struggle for recognition and protection, offering insights for both the conscious traveler and the engaged student of history.

Historical Foundations: A Legacy Etched in Land

To understand the imperative of mapping sacred sites, one must first grasp the depth of connection between Indigenous peoples and their ancestral lands. Before European arrival, Native American societies were inextricably linked to their environment. Sacred sites were integral to daily life, serving as places for ceremonies, vision quests, healing, resource gathering, and the transmission of oral traditions. These were not isolated temples but interconnected nodes within a vast, living spiritual landscape. The relationship was reciprocal: the people cared for the land, and the land sustained the people, both physically and spiritually.

The advent of colonization shattered this equilibrium. European settlers brought with them a worldview that saw land as a commodity to be owned, exploited, and reshaped, rather than a sacred entity to be respected. This fundamental clash of perspectives led to devastating consequences. Forced removal policies, epitomized by the Trail of Tears, severed tribes from their ancestral lands, including countless sacred sites. Treaties, often broken, further diminished Indigenous territories. As the American frontier expanded, sacred sites were routinely desecrated or destroyed by mining, logging, damming, and agricultural development, often without any understanding or regard for their significance. Burial grounds were plowed over, ceremonial grounds became tourist attractions, and mountains considered sacred were dynamited for resources.

This era of systematic dispossession and cultural assault created a deep trauma that reverberates to this day. It underscored the urgent need for a mechanism to identify, document, and protect these invaluable places, not just for the sake of history, but for the survival of Indigenous identities themselves.

Defining "Sacred Site": More Than Just a Dot on a Map

What exactly constitutes a "sacred site" in the Native American context? The definition extends far beyond the Western concept of a church or temple. It encompasses:

- Spiritual and Ceremonial Grounds: Places where specific rituals, prayers, dances, or vision quests have been performed for generations. These might include medicine wheels, kivas, or specific natural formations.

- Burial Grounds and Ancestral Remains: Areas where ancestors are interred, holding immense spiritual and historical weight. The disturbance of these sites is considered a profound desecration.

- Resource Gathering Areas: Places where specific plants, animals, or minerals vital for traditional medicines, crafts, or sustenance are found. These sites are often managed with traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and are integral to cultural survival.

- Historical and Cultural Markers: Locations of significant historical events, battles, migrations, or the setting for creation stories and oral traditions. These sites are living textbooks of Indigenous history.

- Natural Features: Mountains (like Bear Ears or Devils Tower/Mateo Tepee), rivers, lakes, caves, and rock formations that are imbued with spiritual power or are considered dwelling places for spirits or deities.

Crucially, for many Indigenous peoples, the separation of land from spirituality is an artificial construct. The land is the sacred. It is a relative, a teacher, a source of identity, and a repository of collective memory. To harm the land is to harm the people, and to lose a sacred site is to lose a piece of one’s soul, history, and future.

The Emergence of Protection Efforts: A Long Road to Recognition

The struggle for sacred site protection gained momentum in the latter half of the 20th century. While individual tribal efforts had always existed, broader legislative action was necessary to counter federal and state policies. Key milestones include:

- The American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) of 1978: This landmark legislation was intended to protect and preserve the inherent right of American Indians, Eskimos, Aleuts, and Native Hawaiians to believe, express, and exercise their traditional religions. While a crucial symbolic step, AIRFA often lacked the enforcement mechanisms to effectively protect sacred lands from development or desecration, leaving tribes frequently battling in courts.

- The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990: NAGPRA requires federal agencies and museums to return Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to their lineal descendants or culturally affiliated tribes. While primarily focused on repatriation, it indirectly highlighted the sacredness of burial sites and cultural items, fostering a greater understanding of Indigenous heritage.

- National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), particularly Section 106: This act requires federal agencies to identify and assess the effects of their undertakings on historic properties. Section 106 has become a powerful tool for tribes, as it mandates consultation with Native American tribes regarding sites of traditional religious and cultural significance. It allows tribes to raise concerns and negotiate mitigation measures before federal projects proceed.

Despite these legislative advancements, the fight is ongoing. Many sites remain unprotected, threatened by mining, energy development, tourism, and climate change. The lack of uniform protection, conflicting jurisdictional claims, and the ongoing challenge of educating the public and policymakers about the profound significance of these sites continue to fuel the need for robust advocacy.

The Map as a Tool: Visualization for Advocacy and Education

This brings us to the pivotal role of a map of Native American sacred site protection. Such a map is far more than a simple diagram; it is a dynamic, living document that serves multiple critical functions:

-

Advocacy and Policy Influence: A visual representation of sacred sites, their proximity to proposed development, and their relationship to tribal lands provides compelling evidence for policymakers, corporations, and the public. It transforms abstract concepts into tangible realities, illustrating the scope of potential damage and the scale of Indigenous heritage at risk. Maps can highlight areas of overlapping tribal interests, showing the collective impact of land use decisions.

-

Education and Awareness: For non-Native audiences, such a map serves as an invaluable educational tool. It unveils the "unseen landscape" – the spiritual and historical layers that exist beneath the surface of familiar geographies. It teaches that iconic landmarks like the Grand Canyon or Yellowstone are not just natural wonders but deeply sacred spaces with specific Indigenous names, stories, and protocols. This awareness is crucial for fostering respect and promoting responsible engagement.

-

Internal Tribal Documentation and Preservation: For Native American tribes, mapping their sacred sites is an act of self-determination and cultural preservation. It allows them to document ancestral territories, record traditional place names, and identify areas critical for ceremonial practices. This internal mapping can be vital for educating younger generations about their heritage and strengthening cultural identity. Often, specific locations are kept confidential to prevent desecration, with only generalized maps shared publicly.

-

Legal Battles and Land Claims: In courtrooms and administrative hearings, maps provide essential geographical context. They can demonstrate historical occupation, delineate traditional use areas, and show the extent of cultural landscapes, bolstering legal arguments for land rights, access, and protection.

-

Guiding Respectful Engagement: For the conscious traveler or history enthusiast, a sacred site map can guide respectful interaction. It can indicate areas where visitation is encouraged (often with specific protocols), areas where sensitive sites exist (requiring heightened awareness and respect for privacy), and areas that are strictly off-limits due to their sacred nature or fragility. It promotes a shift from mere tourism to thoughtful pilgrimage or educational engagement.

Such a map might not only show the locations of known sacred sites (often anonymized or generalized for protection) but also overlay information about:

- Tribal territories and historical boundaries.

- Threats like mining leases, oil and gas exploration, logging permits.

- Protected areas like National Parks or Wilderness Areas, and how tribal access and management often conflict with federal mandates.

- Areas of ongoing land back movements or successful protection campaigns.

Identity and Belonging: Land as the Core of Native Self

At its heart, the effort to map and protect sacred sites is a profound assertion of Indigenous identity. For many Native Americans, identity is not merely a social construct but is intrinsically tied to the land, their language, and their ceremonies.

- Cultural Resilience: Protecting sacred sites is a direct act of preserving culture. When a site is protected, the ceremonies associated with it can continue, the stories can be told in their proper context, and traditional ecological knowledge can be practiced. This ensures the vitality of cultural practices for future generations.

- Sovereignty and Self-Determination: The ability of a tribe to protect its sacred sites is a fundamental expression of its sovereignty. It asserts the right of Indigenous nations to govern themselves and manage their heritage according to their own values and laws, independent of external impositions.

- Intergenerational Connection: Sacred sites are bridges between generations. They are where ancestors lived, worshipped, and were buried, and where future generations will learn and connect. Their loss is a break in the chain of memory and identity.

- Spiritual Well-being: The health of the land is directly linked to the spiritual health of the people. Desecration of sacred sites causes deep spiritual harm and distress, impacting the collective well-being of the community. Protecting them is an act of healing.

- "We Are the Land": This powerful Indigenous philosophical concept encapsulates the inseparability of people and place. Identity is not just from the land but is the land. Therefore, a map of sacred sites is, in essence, a map of Indigenous identity and a declaration of continued existence.

Challenges and Ongoing Struggles

Despite advancements, the challenges in sacred site protection remain formidable:

- Confidentiality vs. Protection: A persistent dilemma is whether to publicly reveal the exact locations of sacred sites. While mapping aids advocacy, it can also expose sites to vandalism, theft, or inappropriate tourism. Many tribes prefer to keep specific details confidential, sharing only generalized information or working through trusted intermediaries.

- Conflicting Interests: The drive for economic development (mining, logging, energy extraction, tourism) frequently clashes with cultural preservation. Corporations often prioritize profit, and governments prioritize resource extraction, leading to intense battles over land use.

- Jurisdictional Complexity: The patchwork of federal, state, tribal, and private land ownership creates a complex legal and administrative landscape, making comprehensive protection difficult.

- Lack of Enforcement: Even with protective laws, enforcement can be weak, and penalties for desecration often insufficient to deter powerful interests.

- Appropriation and Misinterpretation: The spiritual significance of some sites is sometimes appropriated by New Age movements or misunderstood by tourists, leading to disrespectful behavior or commercial exploitation.

- Climate Change: A new and growing threat, as changing environmental conditions impact traditional ecological systems and alter the very landscapes that are considered sacred.

The Role of the Traveler and Educator

For anyone interested in history, culture, and responsible travel, understanding the significance of Native American sacred sites is paramount.

- Educate Yourself: Learn about the Indigenous history of the lands you inhabit and visit. Understand which tribes are the traditional custodians of the area.

- Respect Protocols: If visiting a site that is open to the public, adhere strictly to any posted rules or tribal requests. Some sites may require a guide, a permit, or have specific restrictions on photography, noise, or behavior.

- Listen to Native Voices: Prioritize and amplify the perspectives of Indigenous peoples regarding their sacred sites. Support their efforts to protect these places.

- Avoid Appropriation: Do not engage in activities that mimic or appropriate Indigenous spiritual practices without direct invitation and guidance from tribal members.

- Advocate for Protection: Support legislation and initiatives that empower tribes to protect their sacred lands. Educate others about the importance of these sites.

- Practice Land Acknowledgment: Acknowledge the traditional Indigenous inhabitants of the land you are on, recognizing their enduring connection and sovereignty.

Conclusion: A Living Map, A Continuing Journey

A map of Native American sacred site protection is far more than an academic exercise; it is a testament to the enduring spirit and profound connection to land that defines Indigenous peoples. It is a tool of empowerment, a historical record, and a call to action. Each line, boundary, and marker on such a map tells a story of survival, resistance, and the unwavering determination to preserve a heritage deeply rooted in the North American continent.

These maps are not static; they are living documents that reflect ongoing struggles and triumphs. They remind us that the landscapes we traverse are not empty spaces but are imbued with layers of meaning, history, and sacredness. For the conscious traveler and engaged global citizen, understanding this "unseen landscape" is an invitation to deeper respect, responsible engagement, and a commitment to supporting the Indigenous peoples who continue to protect these irreplaceable cultural treasures. The land speaks, and it is our collective responsibility to listen.