The Enduring Heartbeat: Understanding the Map of Native American Rural Populations

Forget the simplistic images of tipis and buffalo that often dominate popular perception. To truly understand the living, breathing reality of Native America today, one must look at its maps – specifically, the intricate, vibrant, and often heartbreaking cartography of Native American rural populations. This isn’t just a static representation of land; it’s a dynamic testament to resilience, sovereignty, and the profound, enduring connection between identity and place. For travelers seeking deeper meaning and learners hungry for authentic history, this map is your indispensable guide to a story still being written.

The Map as a Living Document: Beyond the Obvious Lines

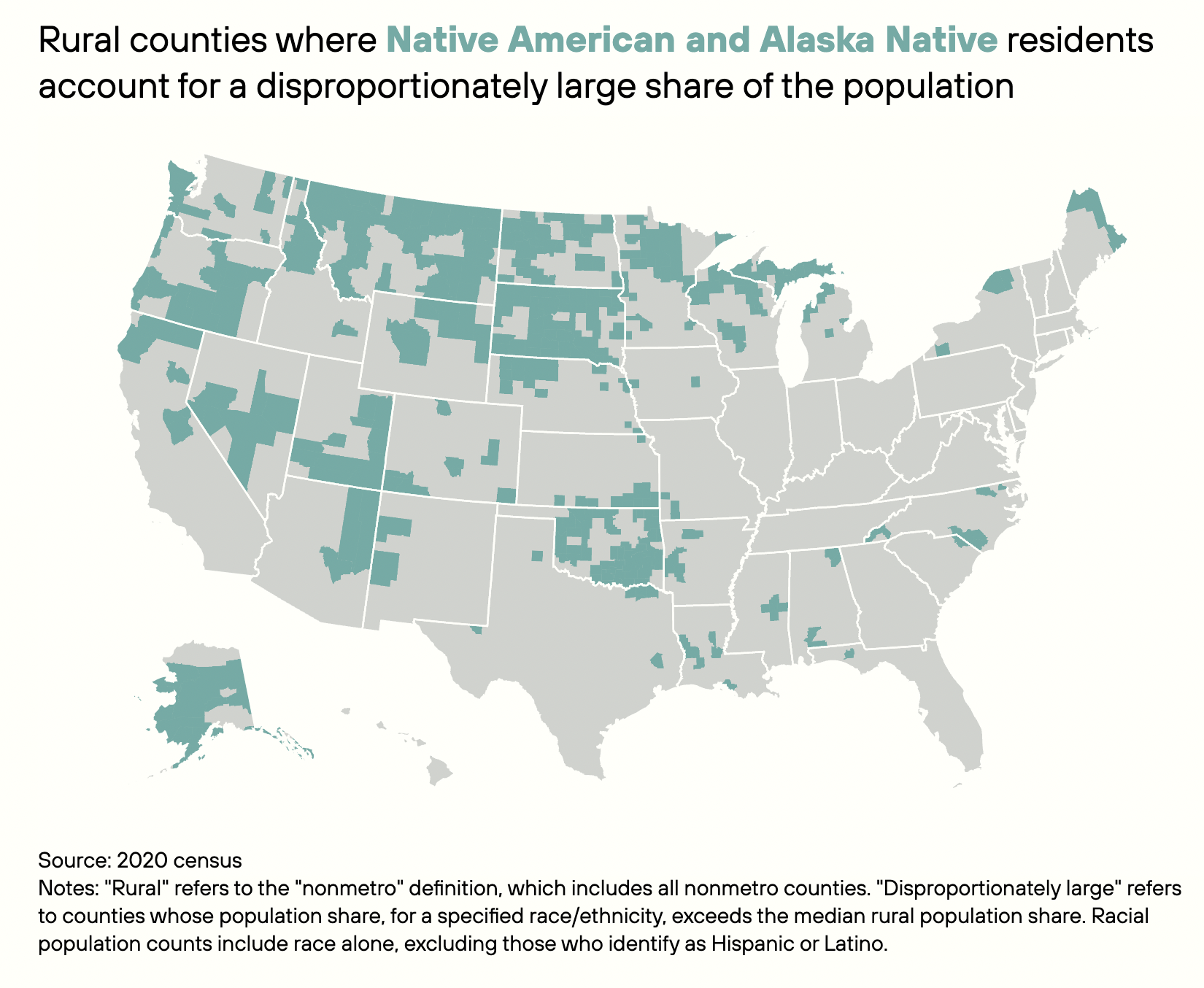

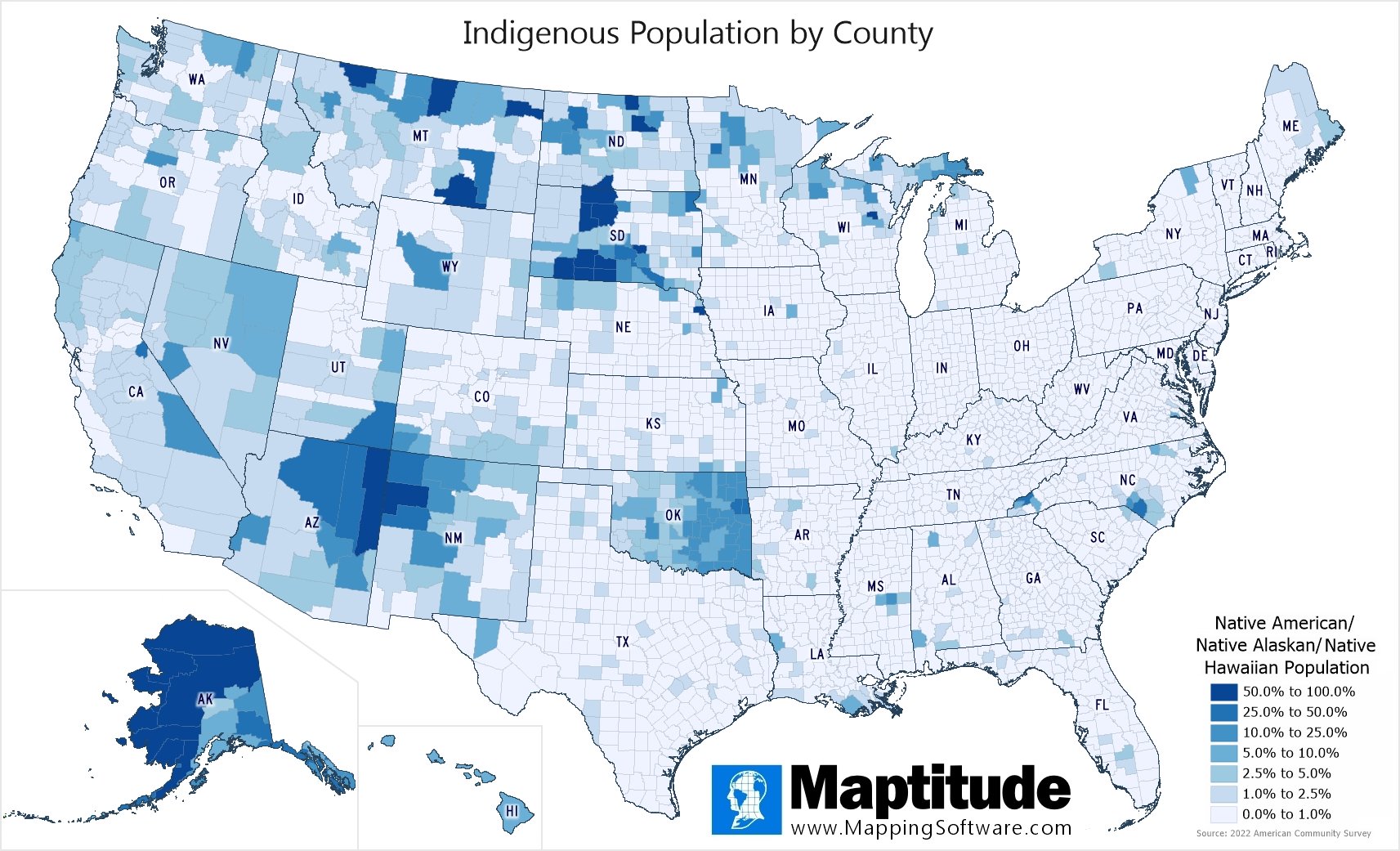

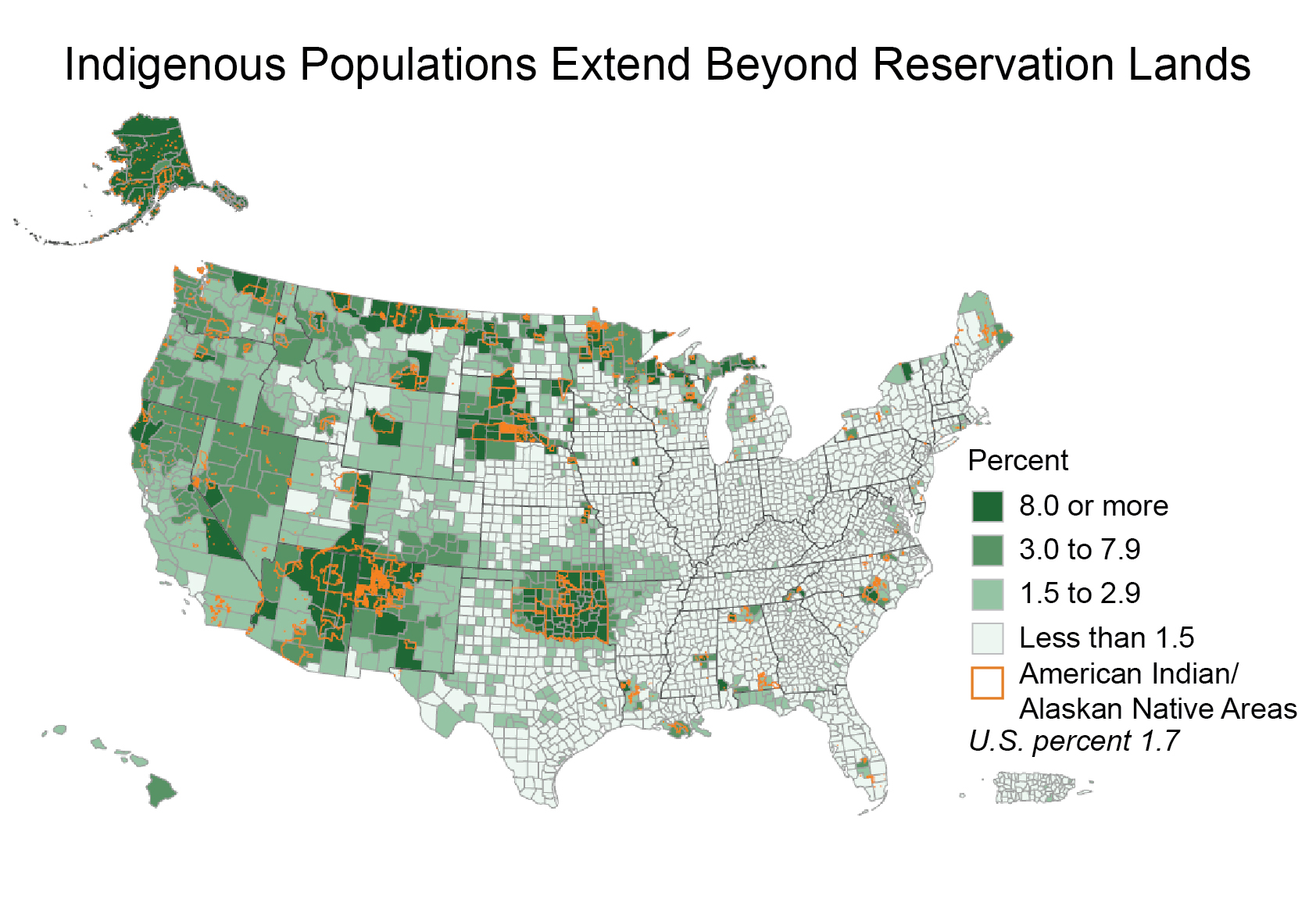

At first glance, a map of Native American rural populations might show a patchwork of federally recognized reservations, trust lands, and off-reservation communities. But these lines, often appearing starkly different from surrounding county boundaries, tell a story far richer than mere geography. They delineate areas where Indigenous nations maintain a cultural and political presence, where tribal governments exercise sovereignty, and where traditional ways of life continue to thrive amidst modern challenges.

These rural areas are the geographic anchors for hundreds of distinct Native American tribes and nations across the United States. While urban Indigenous populations are significant and growing, the rural map highlights the communities that have maintained the strongest continuous ties to their ancestral lands, often despite centuries of displacement and attempts at assimilation. This isn’t just about land ownership; it’s about land stewardship, a relationship deeply embedded in spiritual, cultural, and political identity.

A Deep Dive into History: Shaping the Modern Map

To comprehend the current map, we must journey through a history of immense complexity and profound impact. The current distribution of Native American rural populations is a direct consequence of this tumultuous past:

1. Pre-Contact: A Continent of Nations: Before European colonization, North America was a mosaic of thousands of distinct Indigenous nations, each with its own language, culture, governance, and vast ancestral territories. The map then would have shown a vibrant, continuous Indigenous presence across the entire continent, with communities intimately connected to specific ecosystems and resources. This pre-existing tapestry of nations is the foundational layer upon which all subsequent history is built.

2. Colonialism and Displacement: The Initial Erosion: European arrival brought disease, warfare, and an insatiable hunger for land. Treaties, often broken or coerced, began to shrink Indigenous territories. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 epitomized this era, forcibly relocating Eastern tribes like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) along the devastating "Trail of Tears." This act created some of the earliest large-scale concentrations of displaced Indigenous populations in designated rural areas, far from their original homelands.

3. The Reservation System: Containment and Control: As the United States expanded westward, the dominant policy shifted to confining Native Americans to "reservations." These were tracts of land "reserved" by tribes, often through treaties, or set aside by executive order, in exchange for vast ancestral territories. The intention was often dual: to open up land for white settlement and to "civilize" and assimilate Indigenous peoples.

- Treaty Reservations: Many tribes secured their reservations through negotiated treaties with the U.S. government. These reservations often represent a fraction of their original lands but are legally significant as they were formally recognized agreements between sovereign nations.

- Executive Order Reservations: Other reservations were established by presidential executive order, often for tribes that had not signed treaties or whose treaty lands had been further diminished. These tended to be more vulnerable to future land grabs.

The creation of reservations dramatically altered the map, concentrating diverse Indigenous groups into specific, often isolated, rural areas. These were not chosen for their fertility or resources but for their perceived remoteness and ease of control.

4. Allotment and Assimilation (Dawes Act, 1887): Further Fragmentation: The Dawes Act was a catastrophic blow to the communal land base of Native nations. It aimed to break up reservations into individual land allotments (typically 160 acres) for tribal members, with the "surplus" land then sold off to non-Native settlers. The stated goal was to encourage individual land ownership and assimilation into American farming society.

The result was devastating: over two-thirds of the remaining reservation land was lost, often the most fertile portions. This policy created the "checkerboard" pattern seen on many reservation maps today, where tribal lands are interspersed with privately owned non-Native parcels. This fragmentation continues to pose significant challenges for tribal governance, resource management, and economic development in rural areas.

5. 20th Century Shifts: From Reorganization to Self-Determination:

- Indian Reorganization Act (IRA, 1934): This act marked a shift away from allotment, halting the sale of "surplus" land and encouraging tribes to re-establish their governments under federal recognition. It allowed for some consolidation of land and laid the groundwork for modern tribal sovereignty, impacting the structure of rural tribal governance.

- Termination Era (1950s-1960s): A brief but damaging period where the U.S. government sought to "terminate" its trust relationship with certain tribes, ending federal services and withdrawing recognition. This resulted in further land loss and economic hardship, pushing many Indigenous people into urban centers.

- Self-Determination Era (1970s-Present): This era ushered in a new policy of tribal self-governance and self-sufficiency. Tribes gained greater control over their land, resources, and programs. While this didn’t significantly expand the land base, it empowered tribal governments to manage and develop their existing rural territories according to their own priorities, strengthening their presence on the map.

Today, the map reflects this layered history: reservations, trust lands, individually allotted lands, and parcels owned by non-Natives, all coexisting within defined tribal boundaries. Each line, each boundary, tells a story of survival, loss, and tenacious cultural endurance.

Identity Woven into the Land: The Rural Experience

For Native American rural populations, identity is inextricably linked to the land they inhabit. This connection is multifaceted and forms the very bedrock of their existence:

1. Cultural Preservation and Continuity: Rural reservations and communities are often the primary bastions of traditional culture. Here, ancestral languages are spoken, sacred ceremonies are performed, oral histories are passed down through generations, and traditional ecological knowledge is maintained. The land itself is a living library, holding the stories, spiritual sites, and resources essential for cultural practice. A deep connection to specific places, landmarks, and ecosystems is fundamental to many tribal identities.

2. Sovereignty and Self-Governance: These rural territories are the physical embodiment of tribal sovereignty. Within their boundaries, tribal governments operate with inherent authority, establishing their own laws, judicial systems, and economic development initiatives. This self-governance is not merely a political concept; it’s a cultural imperative, allowing communities to shape their own destinies and protect their distinct ways of life on their own terms. The map shows where this self-determination is actively exercised.

3. Community and Kinship: Rural Native communities are characterized by strong kinship ties and a deep sense of collective identity. Extended families often live in close proximity, fostering robust social networks and mutual support systems. This communal structure is vital for cultural transmission, elder care, and the resilience needed to face ongoing challenges. The isolation that can come with rural life for other populations is often mitigated by these strong community bonds within Native nations.

4. Spiritual Connection to Place: For many Native nations, the land is not merely property but a sacred entity, a living relative. Mountains, rivers, forests, and specific sites hold profound spiritual significance, acting as places of prayer, healing, and cultural memory. This spiritual bond informs land management practices, environmental activism, and the very worldview of the people. The map, therefore, is also a spiritual atlas.

5. Challenges and Resilience: While the rural context offers profound advantages for cultural continuity, it also presents unique challenges. Many rural Native communities grapple with limited access to essential services like healthcare, broadband internet, and quality education. Economic development can be hindered by isolation, lack of infrastructure, and the legacy of resource extraction. Environmental justice issues, such as contamination from mining or industrial projects on or near tribal lands, disproportionately affect these populations.

Despite these hurdles, the resilience of Native American rural populations is extraordinary. They are actively engaged in revitalizing languages, asserting water rights, pursuing sustainable economic development, and protecting their lands and resources for future generations. The map is a testament to this ongoing struggle and triumph.

Why This Matters for Travelers and Learners

Understanding the map of Native American rural populations is crucial for anyone seeking a deeper, more respectful engagement with Indigenous cultures.

- Move Beyond Stereotypes: It dismantles the myth of a monolithic "Native American" identity, revealing the rich diversity of nations, each with its own history and relationship to its land.

- Appreciate Sovereignty: It highlights the living reality of tribal sovereignty, reminding us that these are not merely historical sites but contemporary nations with inherent rights and governance structures.

- Encourage Responsible Engagement: For travelers, it fosters a deeper appreciation for the sacredness of land and the importance of respecting tribal protocols, supporting Native-owned businesses, and seeking out educational experiences guided by Indigenous voices. It encourages visits that go beyond superficial tourism to genuine cultural exchange.

- Recognize Ongoing Relevance: It emphasizes that Native American history is not relegated to the past but is a vibrant, ongoing story shaping the present and future of the continent.

The map of Native American rural populations is far more than a geographical diagram. It is a vibrant tapestry woven from centuries of history, resilience, and an unwavering connection to the land. It’s a call to look closer, listen deeper, and understand that the heartbeat of Native America continues to echo powerfully across its ancestral and sovereign territories, inviting us all to learn, respect, and engage with its enduring story.