The map of Native American reservations is not merely a collection of lines and colors on paper; it is a complex, living testament to centuries of conflict, resilience, and the enduring identity of indigenous peoples in North America. Far from being simple land designations, these territories represent a profound historical narrative of dispossession, survival, and the ongoing struggle for self-determination. For the traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this map is crucial to grasping the true depth of America’s past and present.

The Unceded Lands: A Pre-Reservation Landscape

Before the arrival of European colonists, North America was a mosaic of hundreds of sovereign Indigenous nations, each with its own intricate social structures, languages, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated land management practices. Their territories stretched across the continent, defined by ancestral ties, migratory routes, hunting grounds, sacred sites, and inter-tribal agreements. There was no concept of "unclaimed land"; every acre was stewarded and utilized by a specific group.

The arrival of Europeans shattered this equilibrium. Initially, interactions were often characterized by trade and cautious diplomacy. However, as colonial populations grew and their ambitions for land expanded, a pattern of encroachment, broken treaties, and violent conflict emerged. European powers, and later the nascent United States, often negotiated treaties with Native nations, recognizing their sovereignty while simultaneously pressuring them to cede vast tracts of land. These treaties, however, were frequently violated, reinterpreted, or simply ignored as the westward expansion of settlers gained momentum, fueled by ideologies like "Manifest Destiny."

The Era of Removal and "Containment" (1830s – 1880s)

The early 19th century marked a pivotal shift towards a more aggressive federal policy of "Indian Removal." The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced displacement of Southeastern Native nations – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole – from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This brutal forced migration, famously known as the "Trail of Tears," resulted in the deaths of thousands and exemplifies the federal government’s increasing willingness to disregard treaty obligations and human rights in the pursuit of land for white settlement.

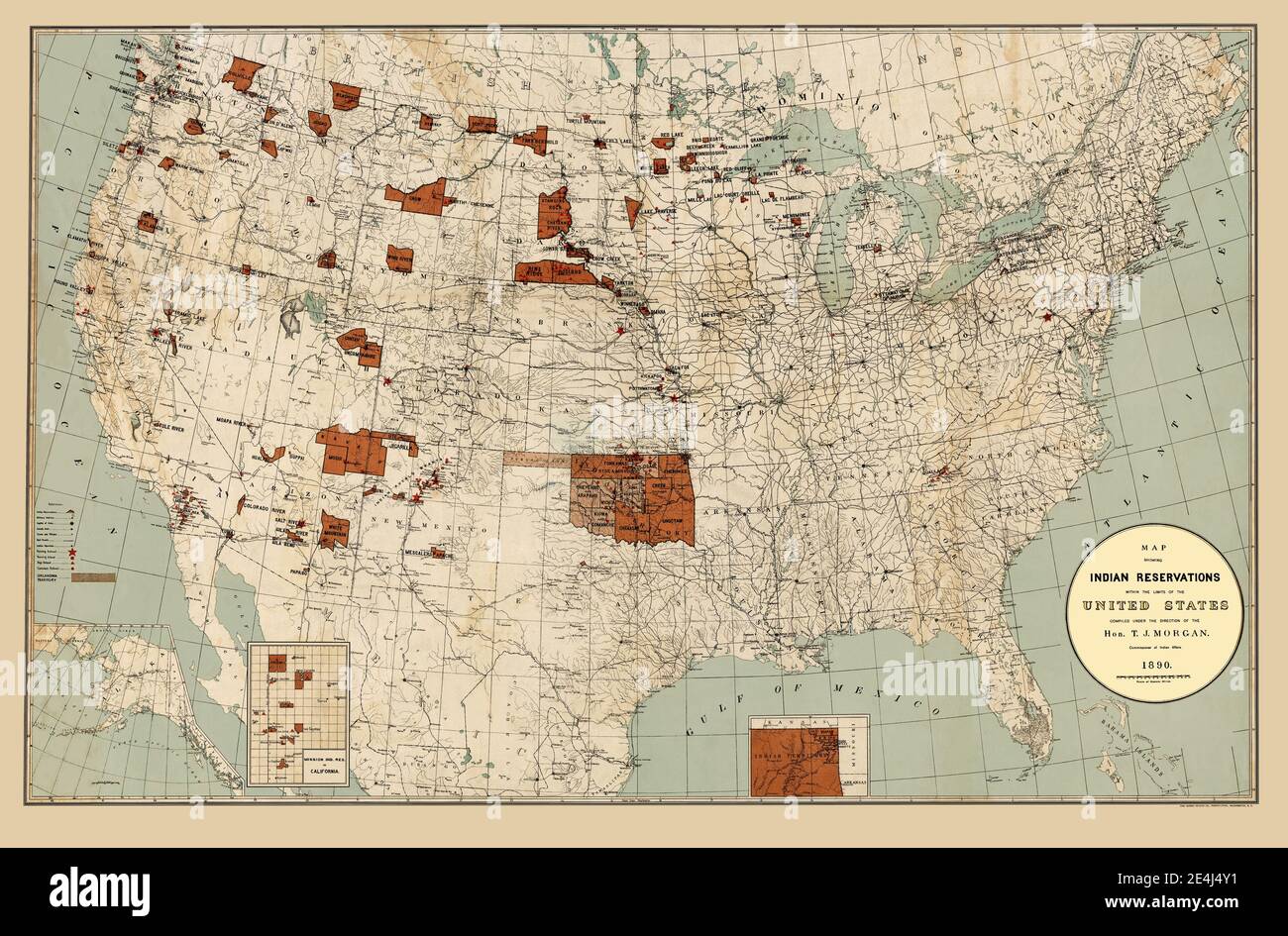

As the United States expanded westward, the concept of "reservations" began to solidify as a primary tool of federal Indian policy. Rather than simply removing tribes, the idea evolved to "contain" them within designated areas. The stated goals were often presented as benevolent: to "civilize" Native peoples, convert them to Christianity, and teach them European agricultural methods. In reality, the primary motivations were to clear valuable lands for settlers, protect westward migration routes, and control Native populations deemed a threat or an impediment to progress.

These early reservations were often established through a combination of treaties (often coerced or signed under duress), executive orders, or congressional acts. The lands "reserved" were typically a fraction of the tribes’ original territories, often undesirable, resource-poor, or located far from their traditional homelands and sacred sites. The federal government, through the newly established Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1824, took on a paternalistic role, managing virtually every aspect of reservation life, from resource allocation to education. This created a system of dependency and eroded tribal self-governance.

Allotment and the Assault on Communal Land (1887 – 1934)

The late 19th century saw another devastating policy shift aimed at further dismantling tribal structures and accelerating assimilation: the General Allotment Act of 1887, also known as the Dawes Act. This act, driven by the belief that private property ownership was essential for "civilization," authorized the President to survey Native American tribal land and divide it into individual allotments for Native American families.

The impact of the Dawes Act was catastrophic. It dissolved communal tribal land ownership, a cornerstone of many Indigenous cultures, and replaced it with an alien concept of individual parcels. Each head of household was typically allotted 160 acres, with smaller allotments for others. The "surplus" land – millions of acres remaining after allotments were made – was then declared "excess" by the federal government and sold off to non-Native settlers and corporations. This single act resulted in the loss of approximately two-thirds of the remaining Native American land base, reducing it from 138 million acres in 1887 to just 48 million acres by 1934.

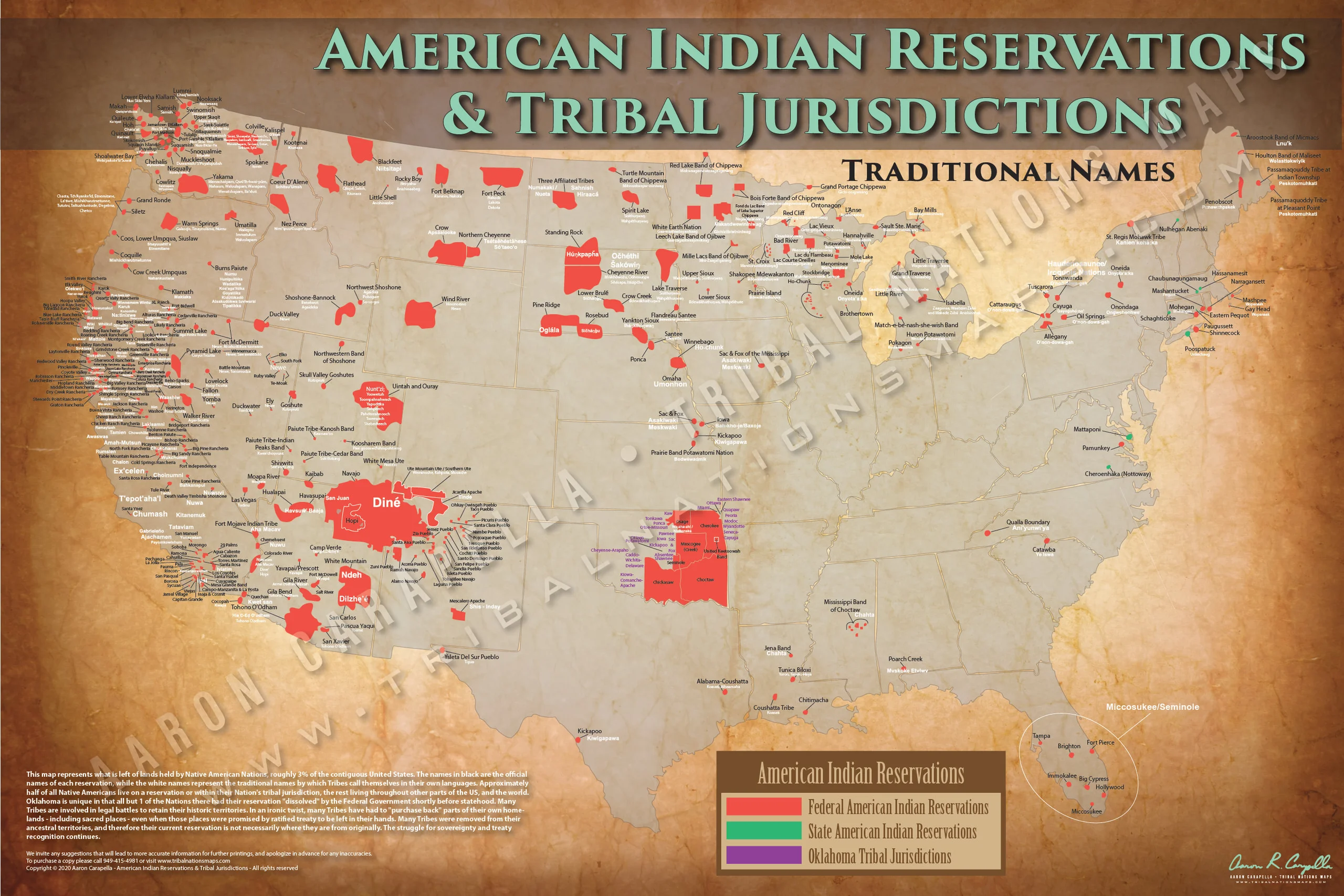

The Dawes Act also created the infamous "checkerboard" pattern of land ownership seen on many reservations today, where tribal lands are interspersed with privately owned non-Native lands. This fragmentation continues to complicate land management, economic development, and the exercise of tribal sovereignty.

Concurrent with allotment, the federal government aggressively pursued a policy of forced assimilation through Indian boarding schools. Native children were forcibly removed from their families, often hundreds or thousands of miles away, forbidden to speak their native languages, practice their spiritual traditions, or wear their traditional clothing. The infamous motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," encapsulated the brutal intent: to eradicate Indigenous cultures and identities.

A Patchwork of Resilience: The Modern Map

The map of Native American reservations today is a complex, often fragmented, and profoundly symbolic landscape. There are over 326 federally recognized Indian reservations in the United States, varying enormously in size, population, and resources. Some, like the Navajo Nation, are vast, spanning parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah, larger than several U.S. states. Others are tiny, encompassing only a few hundred acres.

This geographic distribution reflects the historical processes that shaped them:

- Original Treaty Lands: Some reservations retain a portion of their ancestral lands, albeit greatly reduced.

- Relocated Lands: Many tribes were moved far from their original territories, often to less desirable lands.

- Allotment-Reduced Lands: The Dawes Act severely fragmented many reservations, leading to the checkerboard pattern of tribal, individual Native, and non-Native ownership.

- Terminated Tribes: Some tribes were "terminated" by federal policy in the mid-20th century, losing their federal recognition and land base, only for some to be restored later.

Despite the historical injustices and the often-poor quality of the land, reservations have become powerful symbols of survival and cultural continuity. They are the geographic anchors for tribal nations, providing a base for the exercise of inherent sovereignty, the preservation of culture, and the pursuit of self-determination.

Identity Forged in Adversity

The reservation system, intended to erase Native American identity, inadvertently became a crucible for its preservation and resurgence. While the policies of assimilation inflicted immense trauma, they failed to extinguish the spirit, languages, and traditions of Indigenous peoples.

On reservations today, one finds vibrant cultures that have adapted, endured, and thrived. Efforts to revitalize endangered languages, practice traditional ceremonies, and pass on ancestral knowledge are robust. Art, music, dance, and storytelling remain powerful expressions of identity and connection to heritage. These cultural practices are not relics of the past but living, evolving traditions that define contemporary Native American life.

Tribal identity, forged through shared history, common struggles, and a deep connection to the land, remains incredibly strong. It is an identity rooted in community, kinship, and a unique spiritual relationship with the environment that often stands in stark contrast to mainstream American values.

Sovereignty and Self-Determination: A New Era

From the mid-20th century onwards, a new era of Native American self-determination began to emerge. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 (though not without its own complexities) ended the allotment policy and encouraged tribes to establish their own constitutional governments. Later, the civil rights movement and growing awareness of Native American issues led to policies that emphasized tribal self-governance and economic development.

Today, federally recognized tribes on reservations are sovereign nations within the borders of the United States. This means they have the inherent right to govern themselves, establish their own laws, operate their own courts, manage their own resources, and determine their own membership. While this sovereignty is not absolute and is subject to the plenary power of Congress, it is a fundamental aspect of their existence.

This renewed emphasis on self-determination has led to significant advancements in economic development on many reservations. Industries like gaming (casinos), tourism, energy development, and natural resource management provide jobs and revenue, allowing tribes to fund essential services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. This economic empowerment is crucial for building stronger, more independent communities.

However, reservations continue to face significant challenges. Historical trauma, underfunding of federal programs, inadequate infrastructure, limited access to healthcare and education, and environmental injustices are pervasive. Despite these obstacles, the resilience and determination of Native peoples to thrive on their ancestral and reserved lands remain unwavering.

Navigating the Landscape: A Traveler’s Guide to Understanding

For the respectful traveler, understanding the map of Native American reservations offers an unparalleled opportunity for historical education and cultural immersion. These are not merely historical sites but living, breathing communities with their own governments, economies, and cultural practices.

When visiting a reservation, it is essential to:

- Do Your Research: Understand the specific tribe’s history, culture, and current initiatives. Many tribes have official websites that provide valuable information.

- Seek Permission and Respect Protocols: Always check if areas are open to the public. Some sites are sacred and not accessible. If attending a public event like a powwow, learn about appropriate etiquette. Photography may be restricted.

- Support Tribal Businesses: Purchase authentic arts and crafts directly from tribal members or tribal-owned shops. Eat at local restaurants. Stay at tribal-owned hotels. Your economic support directly benefits the community.

- Visit Tribal Museums and Cultural Centers: These are invaluable resources for learning directly from the source. They offer perspectives and narratives often absent from mainstream historical accounts.

- Be Mindful of Privacy: Reservations are home to families and communities. Respect private property and individuals’ privacy.

- Recognize Sovereignty: Understand that you are entering another nation. Be aware of and respect tribal laws and regulations, which may differ from state or federal laws.

- Listen and Learn: Approach your visit with an open mind and a willingness to learn. Engage respectfully with tribal members if given the opportunity.

The map of Native American reservations tells a story that is both heartbreaking and inspiring. It is a story of profound loss – of land, life, and cultural practices – but also a powerful narrative of resilience, adaptation, and the enduring strength of identity. By engaging with this history and respectfully experiencing contemporary Native American cultures, travelers can gain a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the true tapestry of North America, moving beyond simplistic narratives to embrace the rich, complex, and vital presence of its first peoples.