>

The Resilient Landscape: Unpacking the 1900 Map of Native American Populations

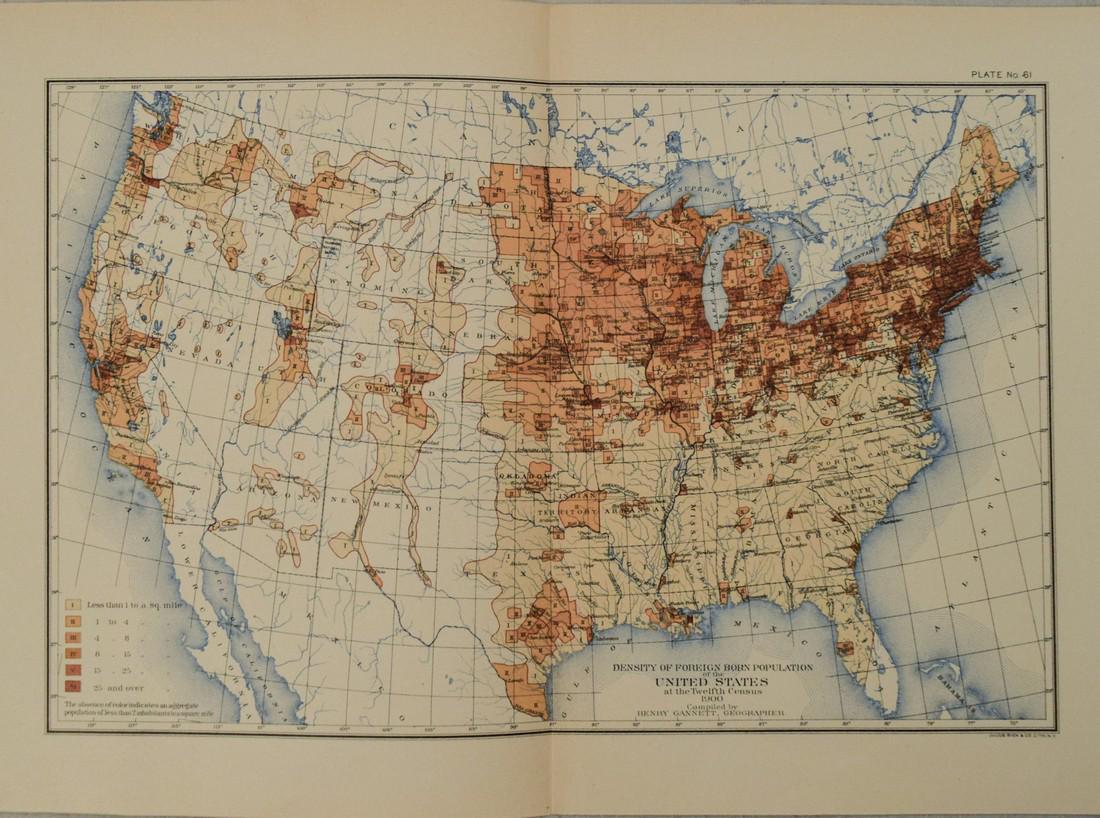

The year 1900 stands as a poignant marker in the history of Native American populations in the United States. A map depicting tribal distributions from this era is not merely a geographical illustration; it is a profound historical document, a testament to immense loss, forced displacement, and astonishing resilience. For anyone seeking to understand the deep roots of American identity, the complexities of its land, and the enduring spirit of its Indigenous peoples, this map serves as an indispensable, albeit heartbreaking, starting point. It’s a snapshot taken long after initial European contact, after centuries of devastating disease, warfare, broken treaties, and genocidal policies, yet it still reveals vibrant cultures persisting against overwhelming odds.

The Context of 1900: A Nation Forged in Displacement

To properly read the 1900 map, one must first grasp the historical landscape upon which it was drawn. By this time, the vast, continent-spanning territories occupied by hundreds of distinct Native nations for millennia had been dramatically reshaped. The relentless westward expansion of the United States, fueled by ideologies of Manifest Destiny and insatiable demand for land and resources, had systematically dispossessed Indigenous peoples.

The 19th century, in particular, was catastrophic. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 led to the forced relocation of Southeastern nations like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole along the infamous "Trail of Tears" to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The Plains Wars, culminating in massacres like Wounded Knee in 1890, effectively crushed armed Native resistance in the West. Simultaneously, federal policies aimed at "civilizing" Native Americans sought to dismantle their communal land ownership, spiritual practices, languages, and traditional governance. The Dawes Act of 1887, for instance, allotted individual parcels of reservation land to tribal members, then sold off millions of acres of "surplus" land to non-Native settlers, fragmenting tribal territories and further eroding their economic and cultural bases.

Thus, the 1900 map does not depict a pre-contact Eden, nor even a landscape where Native nations held substantial independent power. Instead, it illustrates a demographic and geographic reality born of immense suffering, but crucially, also of survival.

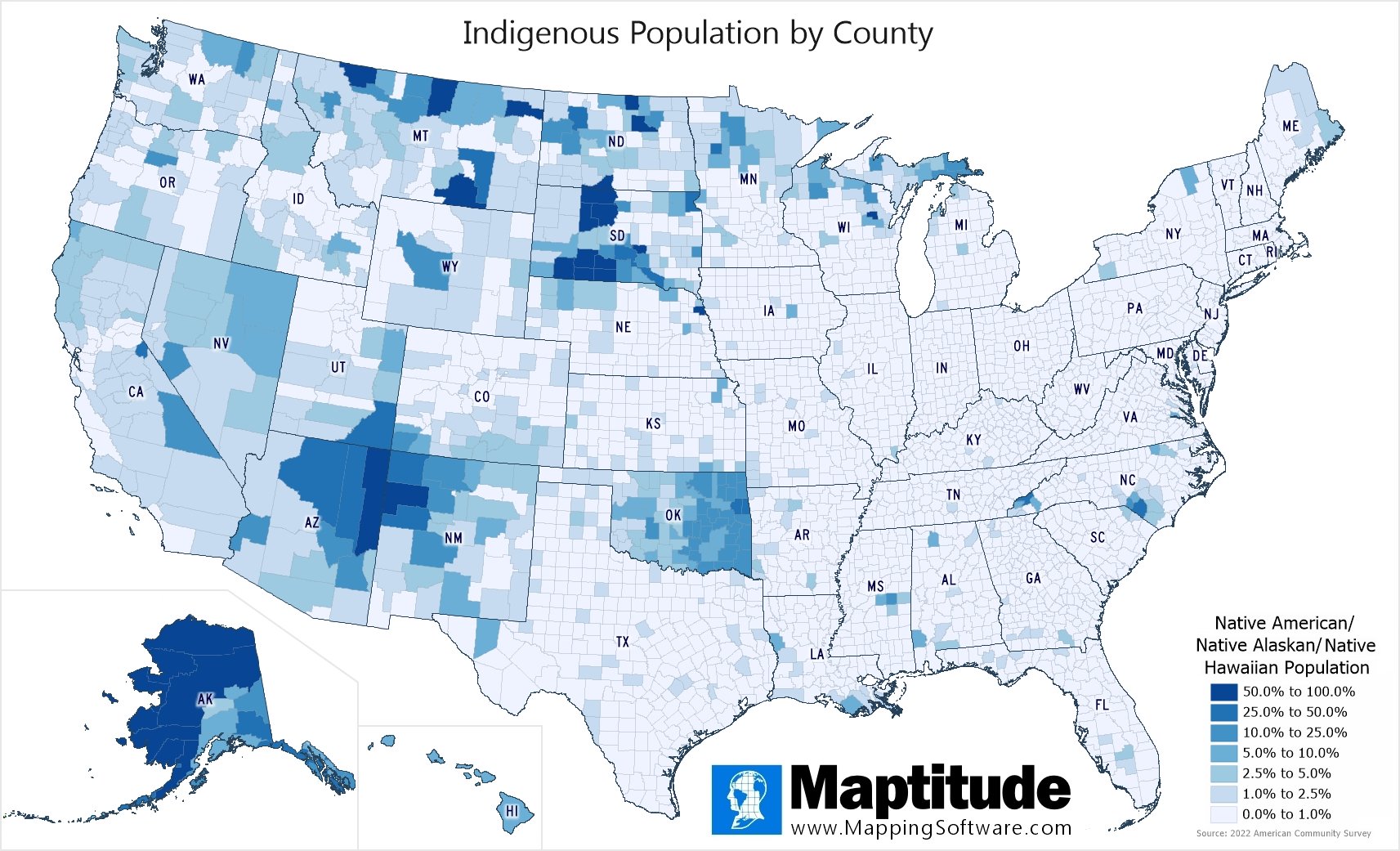

Reading the Map: Pockets of Persistence and Forced Concentrations

Examining the 1900 map, several key patterns emerge. The most striking feature is the heavy concentration of Native American populations in what was then Indian Territory, soon to become Oklahoma. This area, once promised as a permanent homeland for removed tribes, had become a crucible of diverse Indigenous cultures, many forcibly relocated from distant ancestral lands. Here, nations like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole lived alongside Plains tribes who were also pushed into the territory.

Beyond Oklahoma, significant Native populations persisted in the American Southwest, particularly among the Navajo (Diné), Apache, Pueblo peoples, and Tohono O’odham, largely due to their historical resilience, remote homelands, and often successful adaptation strategies. In the Northern Plains, the Lakota, Dakota, and other Sioux nations, along with the Crow and Cheyenne, maintained a presence on their greatly reduced reservations. The Pacific Northwest, despite significant incursions, also showed pockets of thriving Indigenous communities, from the Coast Salish to the Nez Perce.

Conversely, vast swathes of the eastern and central United States, once densely populated by diverse Native nations, appear largely devoid of distinct tribal territories on the 1900 map. This absence is a stark visual reminder of the genocidal impact of disease, warfare, and forced removal that had largely decimated or displaced these populations by the turn of the century. What the map delineates are largely reservations – lands set aside, often forcibly, by treaty or executive order, representing a fraction of original territories, and frequently fragmented or checkerboarded by non-Native settlement due to policies like the Dawes Act. These were not gifts, but remnants, often remote and resource-poor, where Native peoples were confined.

Identity Amidst Adversity: Resilience and Cultural Survival

Despite the dire circumstances depicted by the map, 1900 was not an end, but a pivot point for Native identity. Even confined to reservations, often under the direct supervision of federal agents, Native peoples continued to practice their cultures, speak their languages, and maintain their spiritual beliefs, often in secret or through adaptations.

The boarding school system, aggressively implemented during this period, aimed to "kill the Indian to save the man" by removing Native children from their families, forbidding their languages, and suppressing their cultural practices. Yet, even in these oppressive institutions, children found ways to resist, share their traditions, and maintain a sense of shared identity. Traditional governance structures, though often undermined by federal appointment of "chiefs" or tribal councils, persisted in various forms. Ceremonial dances, oral histories, art, and community networks continued to bind people together, ensuring that identity was not erased but adapted and preserved.

The map, while showing geographical confinement, implicitly speaks to the enduring strength of these identities. Each outlined territory represents a distinct nation, a unique language, a particular worldview, and a collective memory that refused to be extinguished.

The Map as a Legacy of Conflict and Policy

The geographical patterns on the 1900 map are direct consequences of specific U.S. government policies and historical conflicts:

- Indian Removal Act (1830s): The concentration in Oklahoma is the most direct outcome of this policy, which forcibly moved numerous Southeastern tribes across the Mississippi River.

- Plains Wars (1850s-1890s): The creation of large, though diminished, reservations for nations like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho in the Dakotas and Montana resulted from their military defeat and subsequent confinement.

- Dawes Act (General Allotment Act of 1887): This policy, aimed at breaking up communal land ownership and encouraging individual farming, led to the loss of over 90 million acres of Native land by 1934. While the map shows tribal areas, it doesn’t depict the internal fragmentation and loss of "surplus" lands that were already underway by 1900, which further eroded tribal sovereignty and economic self-sufficiency.

- Conquest of the Southwest: The presence of strong Navajo, Apache, and Pueblo communities reflects a different history of resistance and adaptation in a rugged terrain that proved harder for American settlers to fully dominate, though these tribes also suffered immense losses and forced relocation onto reservations.

The map, therefore, is a stark visual representation of a century of land dispossession, treaty violations, and cultural assault. It shows the cumulative effect of policies designed to assimilate or eliminate Native American populations.

Beyond the Lines: What the Map Doesn’t Show

While powerful, the 1900 map also has limitations. It primarily depicts federally recognized tribal lands and concentrations, but misses several crucial aspects of Native American life at the time:

- Urban Indians: Many Native people had already moved to urban centers, either voluntarily or due to economic necessity, often losing direct connection to reservation lands but not necessarily their identity.

- Mixed Heritage: The complexities of identity, intermarriage, and people living off-reservation, who might not be easily categorized by a map of tribal territories.

- Cultural Practices: The map cannot convey the rich tapestry of daily life, the vibrancy of ceremonies, the intricate social structures, or the ongoing oral traditions that thrived within these communities.

- Internal Diversity: It lumps many distinct nations within broad regional outlines; it doesn’t show the hundreds of languages, unique governance systems, or specific cultural nuances within a given area.

- Ongoing Struggles: The map is a static image, but the fight for rights, land, and cultural preservation was, and is, an ongoing dynamic process.

The Map’s Relevance Today: Understanding the Present

For today’s traveler or student of history, the 1900 map is not a relic of a bygone era; it is a vital lens through which to understand contemporary Native American issues. The geographical boundaries and population concentrations depicted laid the groundwork for many of the land claims, sovereignty disputes, socio-economic disparities, and cultural revitalization efforts that continue today.

The map reminds us that tribal nations are not historical footnotes but living, evolving communities with deep roots in this land. Understanding the context of 1900 helps explain why certain tribes are located where they are, why some struggle with poverty while others have found routes to economic development, and why the fight for self-determination and cultural preservation remains so critical.

When we travel through the American landscape, whether it’s the vast plains of South Dakota, the mesas of Arizona, or the forests of Oklahoma, the 1900 map encourages us to look beyond the modern highways and towns. It invites us to see the layers of history, to acknowledge the enduring presence and profound contributions of Native peoples, and to appreciate the incredible resilience that allowed their cultures and identities to persist against unimaginable pressures. It’s a call to responsible tourism, respectful engagement, and a deeper understanding of America’s complex and ongoing story.

>