The Map of Native American Peace Treaties is not merely a collection of lines and colors charting historical land claims; it is a profound and often poignant narrative etched across the North American continent. This cartographic representation is a complex tapestry of diplomacy, broken promises, cultural resilience, and the enduring struggle for sovereignty. For the history enthusiast and the conscientious traveler, understanding this map offers an unparalleled window into the identity and legacy of Indigenous peoples, revealing a history far richer and more nuanced than standard textbooks often portray.

The Sacred Weight of Treaties: An Indigenous Perspective

To comprehend the "Map of Native American Peace Treaties," one must first grasp the indigenous understanding of a treaty. For Native nations, treaties were sacred pacts, often forged through elaborate ceremonies, binding future generations, and viewed as nation-to-nation agreements between sovereign entities. They were not merely legal documents but foundational statements of relationship, reciprocity, and mutual respect, often involving the exchange of wampum belts or other symbolic items to signify their enduring nature. Land, in particular, was not a commodity to be "owned" in the European sense but a living entity, an ancestral inheritance to be stewarded, connected to spiritual identity and the very survival of the people.

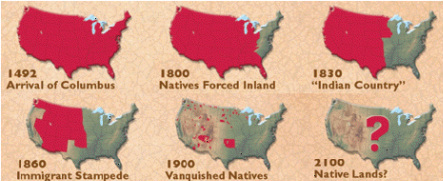

The United States, conversely, generally viewed treaties as expedient tools for land acquisition, temporary measures to manage the "Indian problem," or legalistic instruments that could be unilaterally reinterpreted or abrogated when convenient. This fundamental divergence in understanding set the stage for centuries of conflict and betrayal, visibly documented on the map as vast ancestral lands progressively shrink into confined reservations.

Early Encounters and the Seeds of Dispossession

The earliest treaties reflected the initial balance of power, where European colonists often relied on Native alliances for survival and trade. Nations like the Iroquois Confederacy, the Cherokee, and the Creek held significant sway, negotiating with the British, French, and later the nascent United States as equals. These early maps depict sprawling tribal territories, vibrant with distinct cultures, languages, and governance structures. Treaties from this era, such as the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1768) with the Iroquois or the Treaty of Hopewell (1785) with the Cherokee, attempted to establish boundaries and regulate trade.

However, even in these early agreements, the seeds of future dispossession were sown. European concepts of land ownership, often based on written deeds and surveys, clashed with indigenous communal land use and spiritual connection. The very act of "ceding" land, understood by Europeans as outright ownership transfer, was often interpreted by Native signatories as granting shared use rights or hunting access, not a permanent relinquishment of sovereignty.

The Age of Manifest Destiny and the Cartographic Betrayal

The 19th century ushered in an era of aggressive westward expansion, driven by the ideology of Manifest Destiny – the belief in America’s divine right to expand across the continent. This period saw a dramatic escalation in treaty-making, often under duress, and an equally dramatic erosion of Native lands. The map of peace treaties from this era transforms into a stark visual record of systemic land theft.

Key examples stand out:

- The Indian Removal Act (1830): This infamous act, despite its initial framing as voluntary removal, led to the forced relocation of the "Five Civilized Tribes" (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The maps detailing these removals show vast, fertile lands in Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida being cleared for white settlement, replaced by much smaller, arbitrarily drawn parcels far to the west. The "Trail of Tears," the devastating forced march of the Cherokee, became a symbol of this era’s brutality.

- The Fort Laramie Treaties (1851, 1868): These treaties with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and other Plains tribes initially promised vast territories, including the sacred Black Hills, as "unceded Indian territory." The 1868 treaty, signed after Red Cloud’s War, was meant to create a "Great Sioux Reservation" in perpetuity. However, the discovery of gold in the Black Hills quickly led to its violation. Prospectors swarmed in, the U.S. government failed to enforce its own treaty, and eventually, the land was seized. The visual progression on the map shows the immense Sioux territory shrinking drastically, then being further fragmented by subsequent acts like the Dawes Act.

- Treaties in the Pacific Northwest: Tribes like the Nez Perce, Chinook, and Salish entered into numerous treaties, often with Governor Isaac Stevens, ceding millions of acres. These treaties, too, were frequently violated as settlers encroached on promised lands, leading to conflicts like the Nez Perce War (1877) and Chief Joseph’s famous surrender.

On these maps, one can visually trace the violent shrinkage of tribal territories. A vast, intricate network of indigenous nations, each with its own defined and respected boundaries, gives way to a patchwork of isolated, much smaller reservations. The lines on the map cease to represent mutual agreement and instead become markers of conquest and containment. The map, therefore, becomes a cartographic betrayal, illustrating not peace, but the calculated dismantling of sovereign nations.

Identity Forged in Treaty History: Resilience and Self-Determination

Despite the profound injustices, the Map of Native American Peace Treaties is also a testament to incredible resilience and the enduring power of identity. For contemporary Native American nations, these historical treaties are not just relics of the past; they are living documents that form the foundation of their modern sovereignty, their legal claims, and their cultural identity.

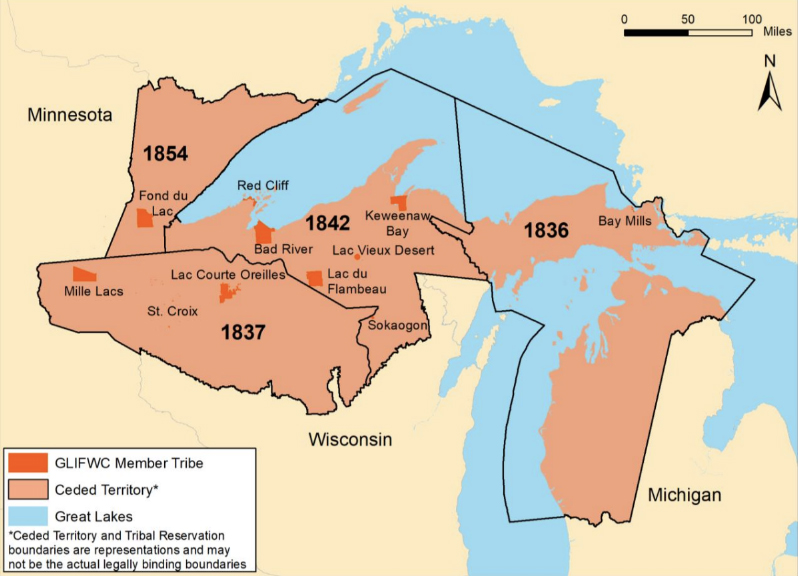

- Legal Basis for Sovereignty: Many tribes today base their governmental structures, their jurisdiction over reservation lands, and their ability to negotiate with federal and state governments directly on the rights and powers guaranteed (or implied) in these historical treaties. Legal battles over land, water rights, hunting and fishing rights, and taxation often hinge on the interpretation of these centuries-old agreements.

- Cultural Survival: The fight to retain ancestral lands, even when unsuccessful, galvanized tribal identity. Languages, ceremonies, oral histories, and spiritual connections to specific places were preserved and adapted, often in secret, despite immense pressure for assimilation. The map, showing the boundaries of modern reservations, also marks the spaces where these cultures have survived, thrived, and are experiencing revitalization.

- Self-Determination: The ongoing movement for self-determination among Native American tribes is deeply rooted in the concept of nationhood recognized (even if imperfectly) by these treaties. It’s a continuous assertion of the right to govern themselves, manage their own resources, and determine their own future, a right that was never truly relinquished.

Beyond the Map: Traveling with Historical Awareness

For the discerning traveler and history educator, the Map of Native American Peace Treaties offers an invaluable framework for understanding the United States. It transforms abstract historical facts into tangible realities.

- Visiting Tribal Lands: When you travel across the U.S., you are almost always on land that was once part of a treaty. Visiting tribal museums, cultural centers, and national parks that are co-managed with Native communities provides an opportunity to engage directly with this history. Learning about the specific treaties that shaped the land you’re standing on deepens your understanding of the landscape and its original inhabitants.

- Supporting Native Economies: Many reservations and tribal enterprises welcome visitors. By supporting Native-owned businesses, artists, and cultural events, travelers can contribute directly to the economic and cultural flourishing of these communities, often directly impacted by the historical injustices depicted on the treaty map.

- Acknowledging Land: A growing practice is "land acknowledgment"—verbally recognizing the traditional Indigenous inhabitants of the land on which one stands. This simple act, informed by an understanding of treaty maps, fosters respect and creates a space for deeper reflection on the layers of history.

- Understanding Ongoing Issues: The legacy of these treaties, and their violations, continues to impact issues such as environmental justice, resource management, and social equity in Native communities today. A traveler who understands the historical context can better appreciate the ongoing struggles and triumphs.

Conclusion: A Living Document of Legacy and Resilience

The Map of Native American Peace Treaties is more than a historical artifact; it is a living document that encapsulates centuries of negotiation, betrayal, and unyielding resilience. It is a visual testament to the immense power dynamics at play during the formation of the United States, the tragic consequences of colonial expansion, and the enduring spirit of Indigenous peoples.

For those seeking to understand the true history of North America, this map serves as an essential guide. It invites us to look beyond simplistic narratives, to acknowledge the complex identities forged in the crucible of treaty-making and treaty-breaking, and to recognize the profound and ongoing contributions of Native American nations. As travelers, educators, and global citizens, our journey into understanding this map is a journey into respecting sovereignty, honoring history, and recognizing the vibrant, continuous presence of the first peoples of this land. It is a call to learn, to listen, and to engage with a past that continues to shape our present and future.