The Living Map: Navigating Native American Oral Traditions as Guides to History, Identity, and Land

Forget the static lines on paper. To truly understand the history, identity, and profound connection to land held by Native American peoples, one must learn to read a different kind of map: the intricate, dynamic, and endlessly rich tapestry of their oral traditions. These aren’t just stories; they are living archives, geographical markers, spiritual blueprints, and ethical guideposts that have shaped cultures for millennia, offering an unparalleled journey into the heart of Indigenous worldviews. For the curious traveler and the dedicated student of history, engaging with these traditions is not merely an academic exercise, but an invitation to perceive the world through a lens far older and deeper than conventional understanding.

The Land as Text: Oral Traditions as Topographical Memory

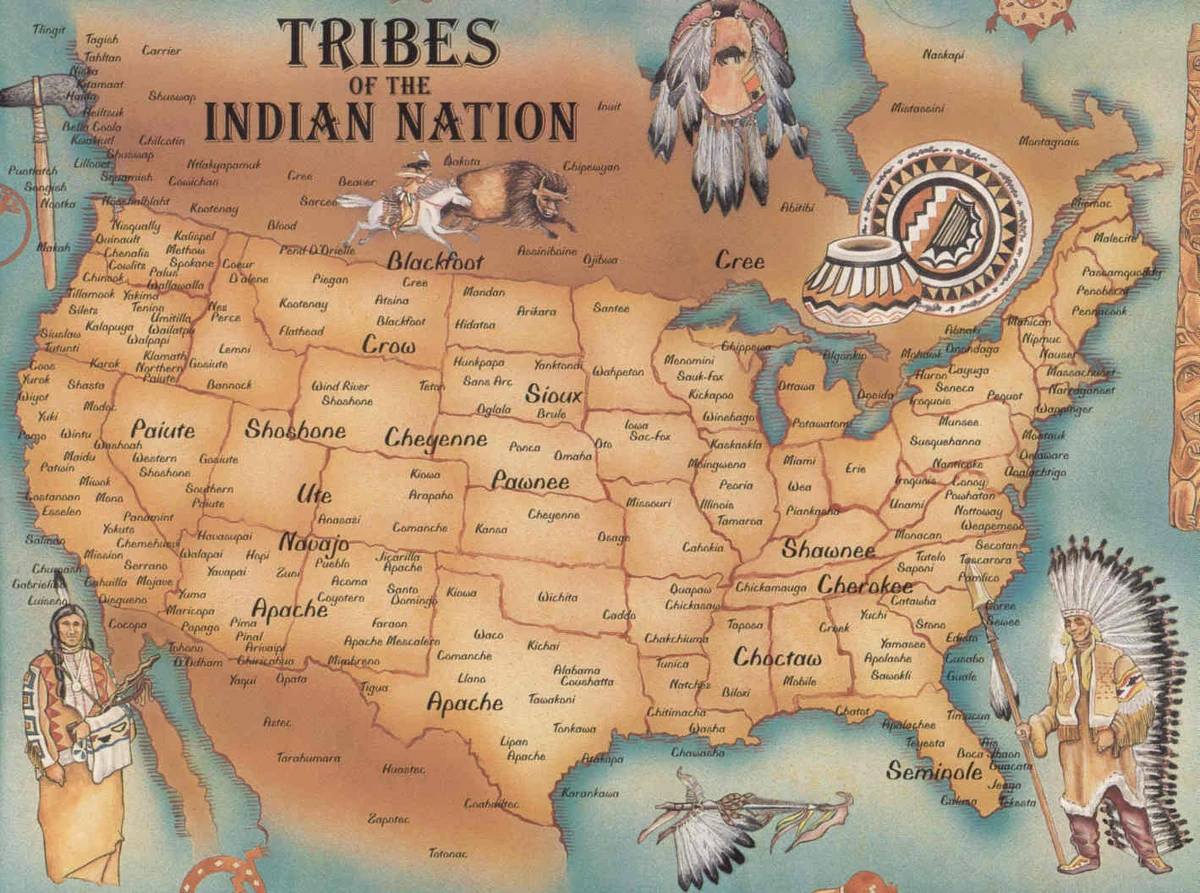

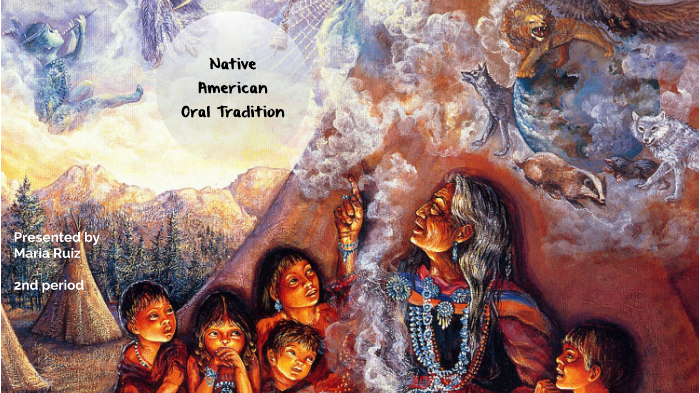

At its core, Native American oral tradition is a sophisticated system of knowledge transmission, meticulously crafted and passed down through generations without the aid of written script. It encompasses a vast array of narratives: creation myths, epic heroes, historical accounts, ceremonial songs, practical ecological knowledge, legal precedents, and moral teachings. Crucially, these traditions are inextricably linked to specific landscapes. A mountain is not just a geological feature; it is the site of a sacred encounter, the resting place of an ancestor, or the location where a specific teaching was revealed. A river bend marks not only a navigational point but also the place where a pivotal battle was fought or a people first emerged.

This deep integration means that the land itself acts as a mnemonic device, a physical manifestation of the collective memory. Walking through ancestral territories, an elder might recount stories tied to every significant landmark, effectively overlaying the physical geography with layers of historical, spiritual, and cultural meaning. This "topographical memory" transforms a simple map of physical features into a complex, multi-dimensional atlas of belonging. It details migration routes, hunting grounds, seasonal camps, sacred sites, and resource locations with an accuracy often underestimated by early European explorers who failed to recognize the sophisticated knowledge systems underpinning these seemingly "unwritten" cultures.

History in the Spoken Word: Unraveling the Past

The historical dimension of Native American oral traditions is immense and often provides the only indigenous perspective on millennia of existence. Before European contact, these narratives served as tribal histories, chronicling the movements of peoples, the formation of alliances, the development of technologies, and the evolution of social structures. For instance, many Southwestern tribes possess detailed migration narratives that trace their ancestors’ journeys across vast distances, often corroborated by archaeological findings. The Iroquois Confederacy’s Great Law of Peace, a complex political and social constitution, was memorized and transmitted orally for centuries, outlining democratic principles that predate many Western models.

The arrival of European colonizers introduced a new, often traumatic, chapter into these oral histories. Stories from this period recount first encounters, the devastating impact of disease, the complexities of treaty negotiations, and the brutal realities of land dispossession and forced removal. These narratives often challenge and correct the dominant historical accounts, which frequently minimize Indigenous agency or cast Native peoples as passive victims. They preserve the memory of resistance, resilience, and survival, detailing how communities adapted, fought back, and maintained their cultural integrity in the face of overwhelming pressure. For example, tales of the Trail of Tears among Cherokee, Choctaw, and other Southeastern tribes are not just accounts of suffering but also testaments to the enduring spirit and communal bonds that allowed survivors to rebuild.

Studying these historical narratives offers an invaluable counter-narrative, enriching our understanding of American history by providing the perspectives of those who were here first and whose experiences were often deliberately erased or marginalized. They remind us that history is not a monolithic narrative but a complex interplay of voices and experiences, each shaped by its unique cultural lens.

Identity Forged in Story: Who We Are, Where We Belong

For Native American peoples, oral traditions are fundamental to individual and collective identity. They answer the fundamental questions: Who are we? Where do we come from? What are our responsibilities? Creation stories, for example, do more than just explain the origins of the world; they define a people’s relationship to the cosmos, to the land, and to all living beings. The Navajo (Diné) emergence story, which details their journey through multiple worlds before arriving in the present one, establishes their deep spiritual connection to Dinétah (Navajo land) and underpins their worldview of interconnectedness and balance. Similarly, the stories of animal-human relationships in many Pacific Northwest cultures reinforce kinship with the natural world and dictate protocols for hunting and resource use.

These narratives transmit ethical frameworks, moral values, and social norms. They teach respect for elders, the importance of reciprocity, the concept of communal responsibility, and the sacredness of all life. Through parables, cautionary tales, and heroic sagas, young people learn the expectations of their community and their place within the larger web of relationships. A person’s identity is often deeply tied to their clan, their lineage, and the stories associated with their family and tribe. To know one’s stories is to know one’s self, one’s people, and one’s place in the world.

The loss of these traditions, therefore, represents not just a cultural void but an existential threat. Colonization often targeted these very systems of knowledge, through forced assimilation, language suppression, and the removal of children to boarding schools. The intent was to sever the connection between people, their stories, and their land, thereby eroding their identity. The ongoing efforts to revitalize Indigenous languages and oral traditions are, therefore, acts of profound cultural and personal reclamation, rebuilding the foundations of identity that were deliberately undermined.

The Sacred Geography: Spiritual Dimensions of the Map

Beyond history and identity, Native American oral traditions map a spiritual geography. Many landscapes are imbued with sacred power, marked by specific ceremonies, prayers, and offerings. These sites – mountains, lakes, caves, springs, specific rock formations – are not merely places but living entities, often connected to powerful beings, spirits, or ancestral figures. Oral narratives explain the significance of these places, detailing the rituals to be performed there, the proper behavior, and the blessings or challenges associated with them.

For example, the Black Hills (Paha Sapa) are central to the Lakota people’s spiritual identity, featuring prominently in their creation stories and sacred ceremonies. Stories describe the origins of their people and their spiritual journey through this land. The forced removal of the Lakota from the Black Hills and the ongoing struggle for its return is not just a political or economic issue; it is a profound spiritual wound, as it disconnects them from their sacred geography and the living map of their spiritual heritage.

Understanding this sacred dimension is critical for anyone engaging with Native American cultures. It highlights why land disputes are rarely just about resources or property; they are often about the preservation of a spiritual lifeline, the continuation of ceremonies, and the maintenance of a relationship with a living, sacred landscape as described and honored through oral traditions.

Engaging with the Living Map: A Traveler’s Guide to Respectful Learning

For those interested in history, culture, and travel, approaching Native American oral traditions requires respect, humility, and a willingness to listen. Here’s how one can responsibly engage with these living maps:

- Seek Authentic Voices: Prioritize learning directly from Indigenous communities, cultural centers, tribal museums, and educational programs led by Native people. Avoid sources that generalize or appropriate.

- Understand Diversity: Native American cultures are incredibly diverse, with over 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. alone, each with unique languages, traditions, and stories. Resist the urge to lump them all together.

- Respect Intellectual Property: Many stories are sacred, ceremonial, or belong to specific families or clans. They are not for public consumption or casual retelling. Learn to appreciate the fact that not all knowledge is meant for everyone.

- Visit Cultural Sites Respectfully: If you visit tribal lands or sites of cultural significance, adhere strictly to local rules and guidelines. These places are often sacred and deserve reverence.

- Support Indigenous Initiatives: Purchase authentic Native art and crafts, support tribal businesses, and donate to organizations dedicated to Indigenous language and cultural revitalization. This helps communities continue to preserve and transmit their traditions.

- Challenge Stereotypes: Educate yourself and others about the rich, complex, and contemporary realities of Native American life, moving beyond outdated and harmful stereotypes.

In conclusion, the map of Native American oral traditions is a vibrant, dynamic, and indispensable guide to understanding the Indigenous experience. It is a testament to the enduring power of story to preserve history, shape identity, and maintain an unbreakable connection to the land. For the curious mind, engaging with these traditions offers not just knowledge, but a profound shift in perspective – a journey into a world where the land breathes with ancient narratives, and every story is a step on a living map of human experience. To learn these stories, to listen with an open heart, is to truly begin to see the world as Indigenous peoples have seen it for millennia: a sacred, interconnected, and endlessly storied place.