The Living Linguistic Landscape: A Journey Through Native American Language Preservation

The "Map of Native American Language Preservation" is far more than a cartographic representation; it is a vibrant testament to resilience, a guide to ongoing cultural reclamation, and a stark reminder of the enduring power of identity. This map, in its various forms across digital and print platforms, charts the ebb and flow of Indigenous languages across North America, highlighting the communities, institutions, and individuals dedicated to ensuring these ancient tongues speak to future generations. For anyone seeking to understand the deep historical tapestry and vibrant contemporary spirit of Native America, this map offers an indispensable lens, revealing not just where languages are spoken, but where cultures are thriving against formidable odds.

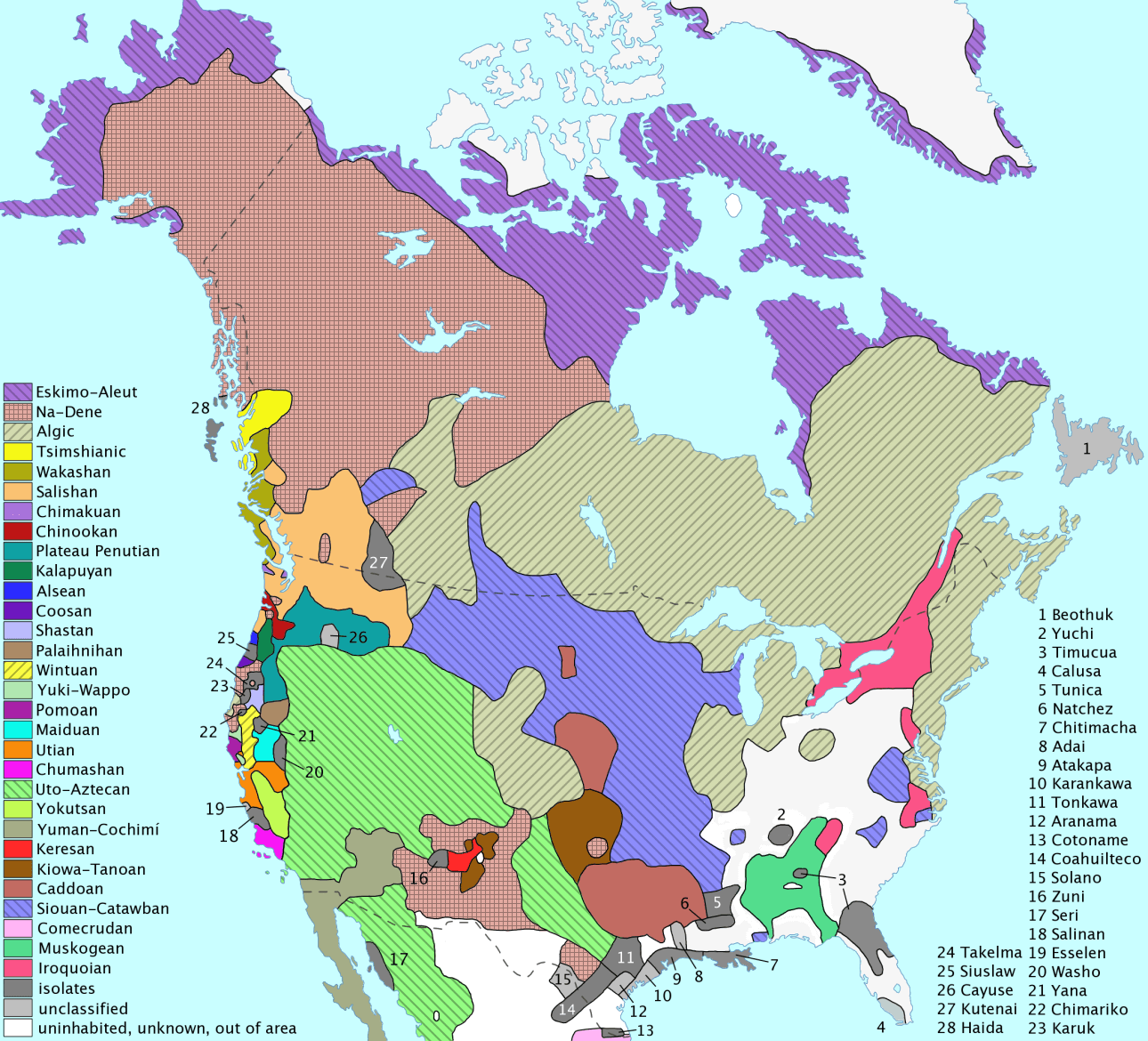

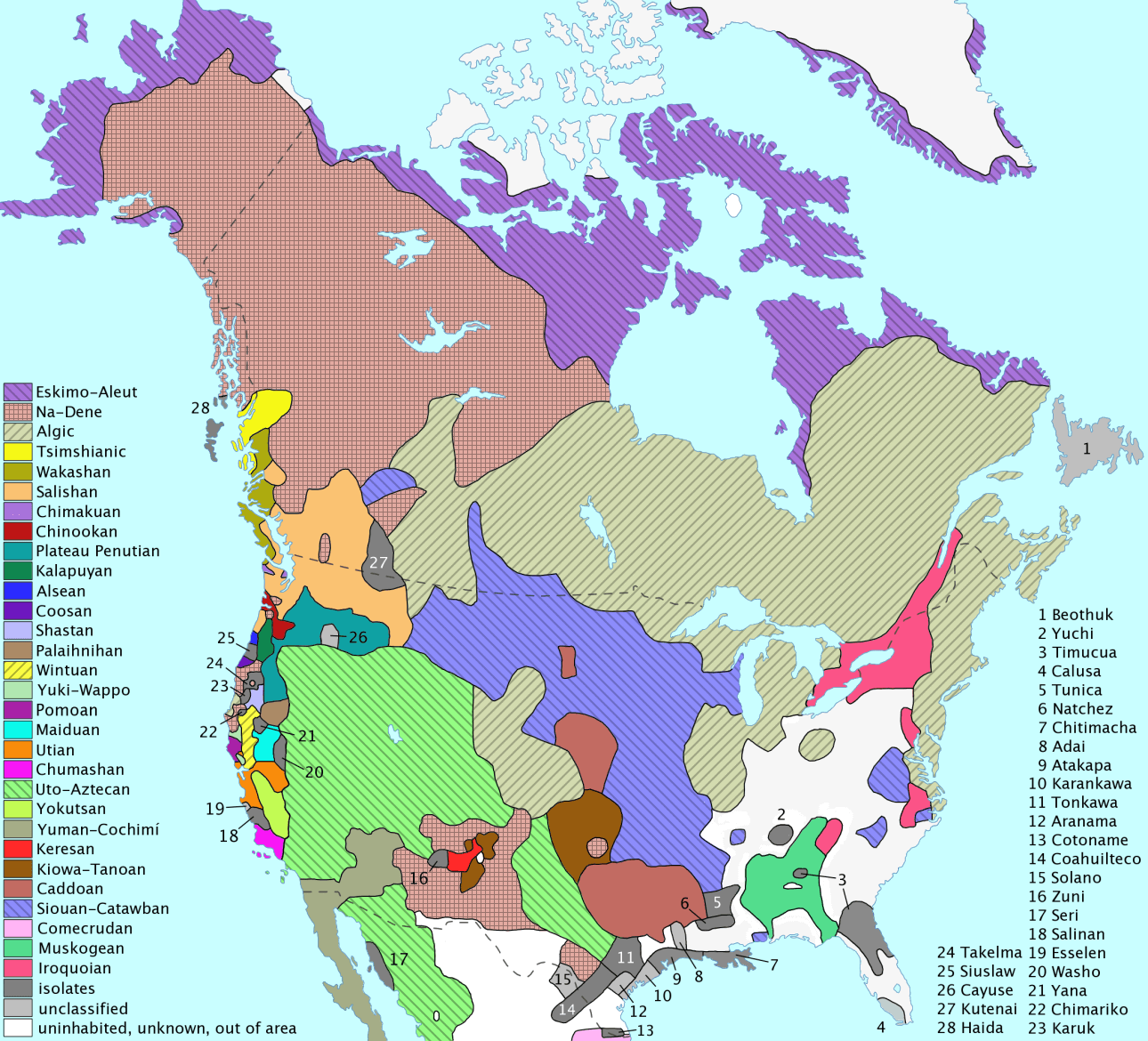

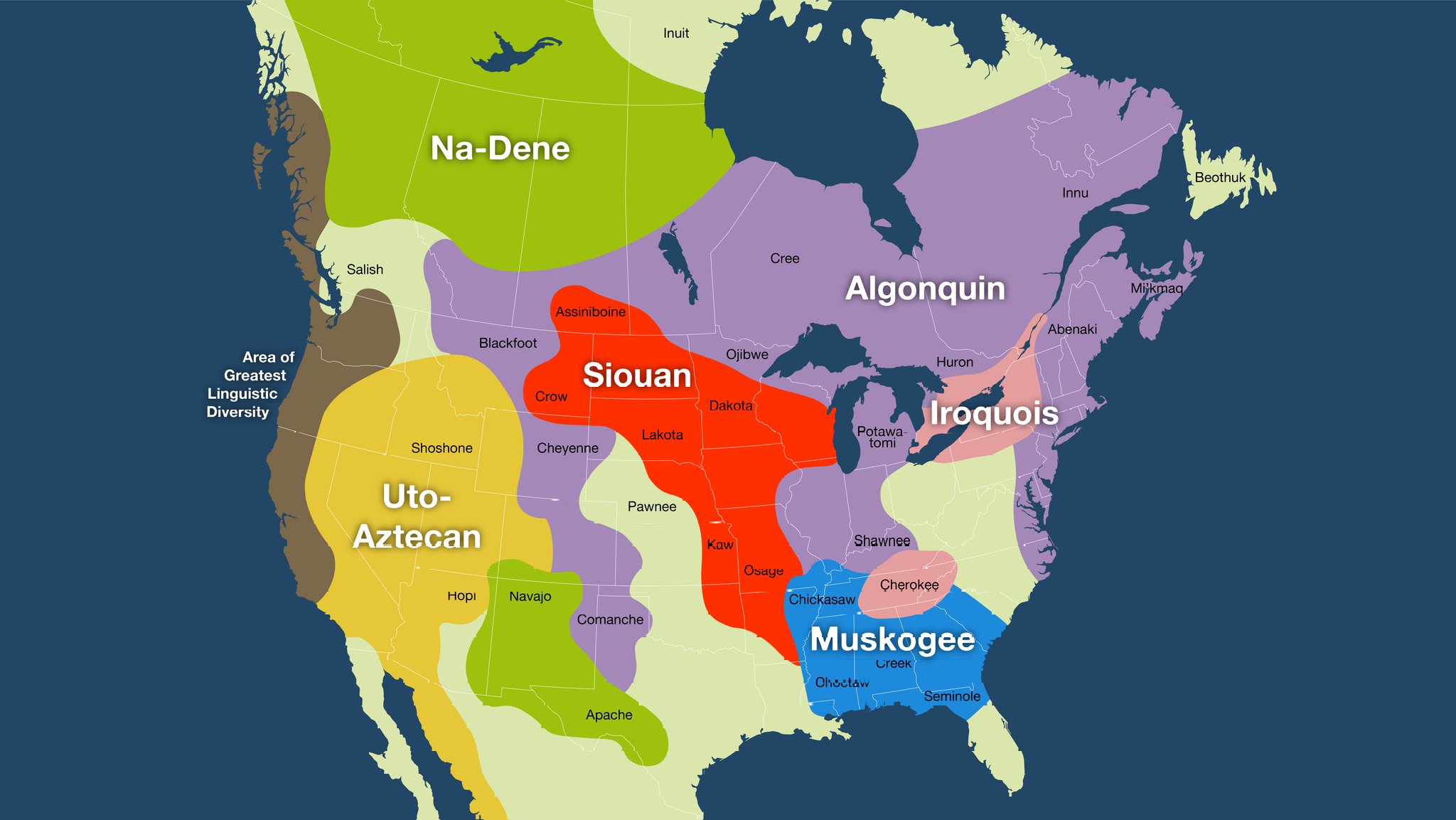

To appreciate the profound significance of this map, one must first grasp the historical context that nearly silenced these languages. Before European contact, North America was a mosaic of linguistic diversity, home to hundreds of distinct language families and thousands of dialects, each embodying unique worldviews, knowledge systems, and connections to the land. From the intricate polysynthetic structures of the Algonquian languages to the tonal complexities of Navajo and the rich oral traditions of the Haudenosaunee, these languages were the very fabric of thriving societies, passed down through millennia of oral tradition.

The arrival of European colonizers marked the beginning of a relentless assault on this linguistic heritage. Initial displacement, disease, and warfare disrupted communities and their language transmission. However, it was the systematic policies enacted by the United States government in the 19th and 20th centuries that proved most devastating. The era of "Manifest Destiny" and the Indian Removal Act were precursors to an assimilationist agenda, culminating in the establishment of Indian boarding schools. These institutions, often run by religious organizations with federal support, pursued the explicit goal of "killing the Indian to save the man." Native children were forcibly removed from their families, forbidden to speak their native languages, punished physically and emotionally for doing so, and stripped of their cultural identities. This policy severed the crucial intergenerational transmission of language, creating "silent generations" who, out of trauma and a desire to protect their children from similar abuse, often did not pass on their mother tongues. By the mid-20th century, many languages were on the brink of extinction, with only a handful of elderly speakers remaining.

The map of language preservation, therefore, tells a story of resistance and resurgence born from this crucible. It illustrates the profound shift from a period of forced suppression to one of active revitalization, largely driven by Native communities themselves. The turning point arrived with the Civil Rights era and the subsequent push for Indian Self-Determination in the 1970s, which saw the passage of landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This act empowered tribes to manage their own affairs, including education and cultural programs. Crucially, the Native American Languages Act (NALA) of 1990 and its subsequent reauthorization in 1992 officially reversed previous destructive policies, declaring that it is the policy of the United States to "preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedom of Native Americans to use, practice, and develop Native American languages." These acts provided a crucial legal and moral framework, along with some federal funding, to support language revitalization efforts.

Central to this map’s narrative is the understanding that language is not merely a tool for communication; it is the very soul of identity. For Indigenous peoples, language embodies worldview, cultural values, spiritual beliefs, traditional ecological knowledge, humor, kinship systems, and specific ways of relating to the land and to each other. When a language is lost, an entire way of knowing and being is diminished. The intricacies of a language often contain concepts that cannot be directly translated into English, offering unique insights into human existence. For example, many Indigenous languages do not have a separate word for "nature," as humans are understood to be an inherent part of the natural world, not separate from it. Losing these linguistic nuances means losing these profound philosophical understandings.

The map highlights various innovative and dedicated mechanisms of preservation. Immersion schools, modeled after the successful Hawaiian language revitalization movement, are considered the gold standard. Here, children learn all subjects exclusively in their ancestral language, fostering fluency from an early age. The map points to communities like the Wampanoag in Massachusetts, who, despite having no fluent speakers for over a century, have brought their language, Wôpanâak, back to life through intense dedication, linguistic analysis of historical documents, and the tireless efforts of figures like Jessie Little Doe Baird. Similarly, the Myaamia (Miami) Nation of Oklahoma has achieved remarkable success in revitalizing their language, which had also fallen silent, through a collaborative effort with Miami University in Ohio.

Beyond immersion schools, the map documents a diverse array of programs:

- Language Camps: Bringing together elders and youth for intensive learning in cultural settings.

- Apprenticeship Programs: Pairing fluent elders with dedicated learners for one-on-one, intensive language transfer.

- Digital Resources: The creation of online dictionaries, language learning apps, social media groups, and YouTube channels, making languages accessible to a wider audience, especially younger generations.

- Community Classes: Regular gatherings where elders teach basic phrases, songs, and stories.

- Curriculum Development: Creating culturally relevant learning materials for all age groups.

- Documentation Projects: Recording and archiving the voices of the last fluent speakers, creating invaluable resources for future learners.

- Teacher Training Programs: Developing certified language instructors to sustain revitalization efforts.

The challenges in these efforts are immense. Many languages have only a handful of elderly first-language speakers, making the race against time a constant pressure. Funding remains a perpetual struggle, and the pervasive dominance of English in media, education, and daily life presents a formidable barrier. Intergenerational trauma also plays a role, as some survivors of boarding schools still carry the pain associated with speaking their language. Yet, the map pulses with stories of triumph: children speaking languages their grandparents never had the chance to learn, new songs being composed, ceremonies being conducted entirely in ancestral tongues, and a renewed sense of pride and cultural identity blossoming across tribal nations.

For the conscious traveler and history enthusiast, the map of Native American language preservation offers an invitation to engage respectfully and meaningfully. It encourages visitors to move beyond superficial understandings and delve into the living cultures that shape this continent. When traveling through areas marked on the map, consider:

- Visiting Tribal Cultural Centers and Museums: Many offer language exhibits, classes, or demonstrations.

- Learning a Few Words: A simple "hello" or "thank you" in the local Indigenous language, respectfully learned, can open doors and demonstrate genuine interest.

- Supporting Indigenous Businesses: Many entrepreneurs use their native languages in their branding or products, directly supporting cultural revitalization.

- Understanding Place Names: Researching the original Indigenous names for natural features and towns can reveal deep historical and cultural connections to the land.

- Attending Public Cultural Events: Powwows, festivals, and cultural gatherings often feature songs, stories, and speeches in native languages.

The Map of Native American Language Preservation is not a static historical document; it is a dynamic, evolving record of a profound cultural movement. It visually represents the fierce dedication of Indigenous peoples to reclaim what was nearly lost, to heal historical wounds, and to ensure that their languages, which carry the wisdom of millennia, continue to enrich the world. It serves as a powerful reminder that these languages are not relics of the past but vibrant, living expressions of identity, sovereignty, and an enduring connection to the land and spirit of Native America. To observe this map is to witness a profound act of self-determination, an ongoing story of survival, and a hopeful blueprint for the future of Indigenous cultures.