The Resurgence Map: Navigating the Living Languages of Native America

Imagine a map, not of borders or battlefields, but of vibrant, pulsing dots. Each dot represents a beacon of hope, a community-led effort to reclaim and revitalize an ancestral tongue. This isn’t just a geographical illustration; it’s a dynamic snapshot of resilience, identity, and the profound power of language. The "Map of Native American Language Immersion Schools" is more than a guide to educational institutions; it’s a testament to survival, a visual narrative of cultural sovereignty reasserting itself across a continent. For the discerning traveler and history enthusiast, understanding this map offers an unparalleled window into the ongoing journey of Native American peoples.

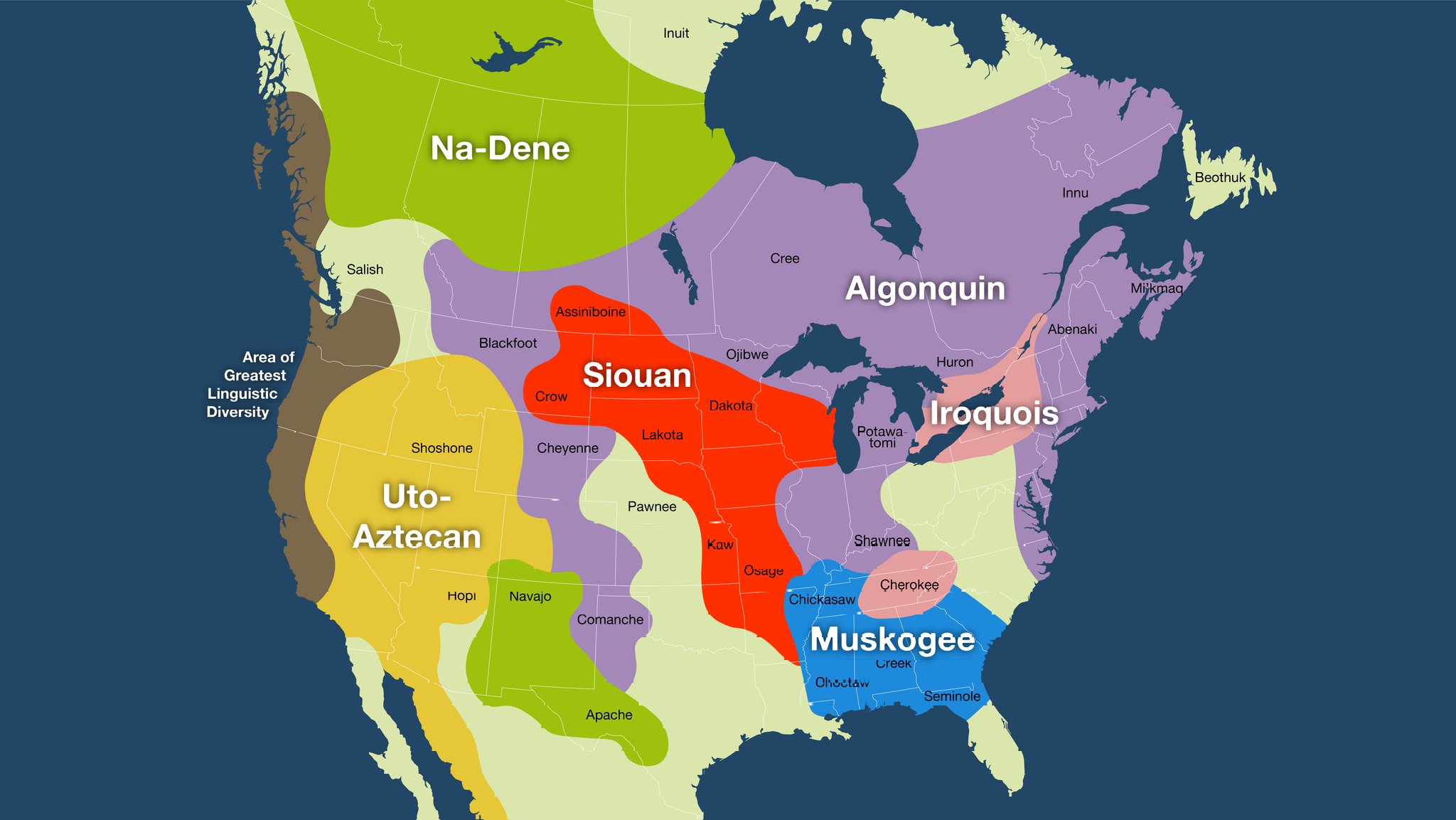

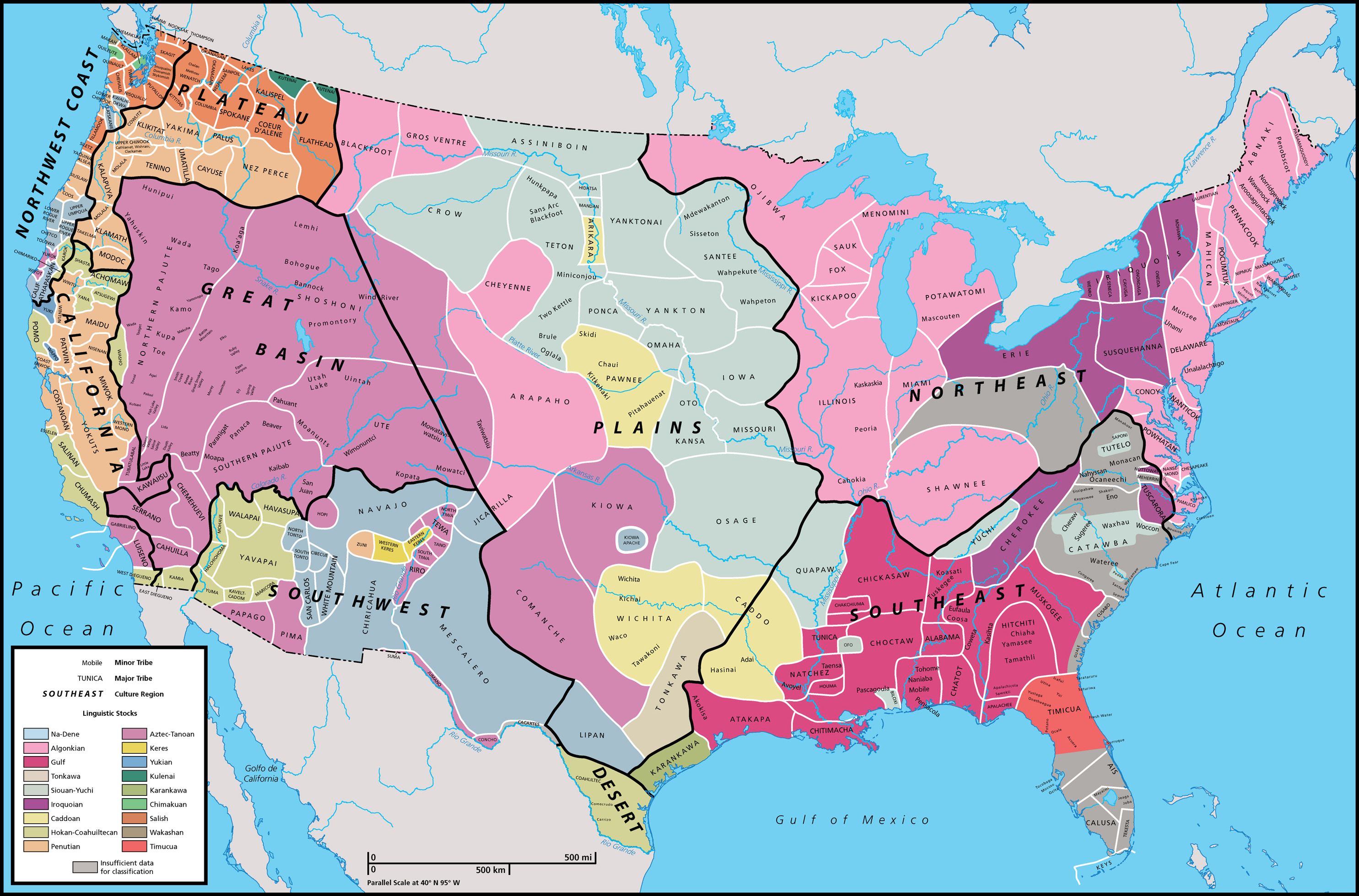

This map, in its various iterations from tribal organizations, academic institutions, and cultural preservation groups, delineates the locations of schools and programs where Indigenous languages are the primary medium of instruction. From the vast Navajo Nation in the Southwest, where children learn Diné Bizaad (Navajo language) from kindergarten through high school, to the Ojibwe immersion schools nestled in the Great Lakes region, fostering Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe language) fluency, these dots represent critical hubs. They are found across diverse landscapes: the Plains, the Pacific Northwest, the Northeast woodlands, and the Southeastern river valleys, each marking a place where children and adults are immersed daily in the sounds, structures, and worldviews of their ancestors.

The significance of these schools cannot be overstated, especially when viewed through the lens of history. Before European contact, North America was a linguistic tapestry of unparalleled complexity. Hundreds of distinct languages, belonging to dozens of language families, flourished, each a complete system of thought, philosophy, and practical knowledge. These languages weren’t merely tools for communication; they were the very fabric of identity, intimately tied to land, ceremony, social structure, and individual well-being. From the intricate tonal systems of some Southwestern languages to the polysynthetic nature of many Pacific Northwest tongues, each offered a unique way of experiencing and understanding the world.

However, the arrival of European colonists heralded a period of catastrophic linguistic decline. The forces were multifaceted: disease, warfare, forced removal, and the deliberate policies of cultural erasure. The 19th and 20th centuries, in particular, witnessed a systematic assault on Indigenous languages, primarily through the devastating institution of Indian boarding schools. These federally mandated and often church-run institutions, operating under the brutal motto "Kill the Indian, Save the Man," actively punished children for speaking their native languages. Tongues were washed with soap, mouths were beaten, and a deep, intergenerational trauma was inflicted, teaching children that their language was shameful, backward, and dangerous. Parents, wanting their children to survive and succeed in a rapidly changing world, often made the agonizing decision to stop speaking their language at home, inadvertently contributing to the decline.

By the mid-20th century, many Native American languages teetered on the brink of extinction. Some had only a handful of fluent elder speakers remaining, and the chain of intergenerational transmission had been severely broken. The urgency was palpable: without immediate and drastic intervention, centuries of unique human knowledge, encapsulated within these languages, would be lost forever.

The tide began to turn with the Civil Rights Movement and, crucially, the era of Indian Self-Determination in the 1970s. With landmark legislation like the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, tribes began to regain control over their own affairs, including education. This empowered communities to challenge the legacy of forced assimilation and embark on a mission of cultural and linguistic reclamation. It was a grassroots movement, driven by the elders who remembered the beauty and power of their languages, and by a new generation determined to heal the wounds of the past.

The concept of language immersion emerged as a powerful solution. Recognizing that second-language acquisition in adults is challenging, and that true fluency requires complete immersion, communities began to establish schools where the ancestral language was not just taught as a subject but was the language of instruction for all subjects – math, science, history, and art. These schools aim to create "new first-language speakers," children who grow up thinking, dreaming, and living in their Indigenous tongue, much as their ancestors did.

The methodology is often rigorous. Teachers, many of whom are themselves products of revitalization efforts or are elder fluent speakers, employ strategies designed to fully immerse students. Classrooms are often adorned with culturally relevant materials, and lessons are integrated with traditional stories, songs, and practices. For example, a math lesson might involve counting traditional crafts or measuring materials for a longhouse. A science lesson might explore traditional ecological knowledge embedded in the language, understanding plant cycles or animal behaviors through an Indigenous lens. The goal is not merely to teach words but to transmit a complete cultural worldview.

The map, therefore, is not just plotting schools; it’s charting the revival of entire worldviews. Each dot represents a place where children are learning that their identity is strong, their history is rich, and their language is a source of immense pride. For the Lakota children in South Dakota learning Lakȟóta, the language is inextricably linked to the sacred Black Hills, to the buffalo, and to the philosophical tenets of Mitákuye Oyásʼiŋ ("All My Relations"). For the Hawaiian youth learning ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi, the language opens up a profound understanding of mālama ʻāina (care for the land) and the complex navigational knowledge of their ancestors.

The impact of these immersion schools extends far beyond linguistic fluency. They are powerful engines of identity formation. Children who grow up speaking their ancestral language often exhibit higher self-esteem, a stronger sense of cultural belonging, and better academic performance across subjects. They are connected to their elders in a way that monolingual English speakers cannot be, bridging generational gaps and fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer. This connection to heritage has been shown to have positive impacts on mental health, reducing rates of depression and suicide in communities where language revitalization is strong.

Furthermore, language revitalization is a fundamental act of sovereignty. By reclaiming their languages, Native American nations are asserting their right to self-determination, to define themselves on their own terms, and to transmit their unique cultural heritage to future generations. It is a powerful rejection of colonial assimilation and a reaffirmation of Indigenous nationhood. These schools are not just teaching language; they are cultivating future leaders, thinkers, and cultural bearers who are grounded in their ancestral traditions while navigating the modern world.

For the traveler interested in history and cultural education, this map offers a profound lesson. It encourages a shift from viewing Native American cultures as relics of the past to understanding them as vibrant, living entities actively shaping their future. While direct visitation to immersion schools might not always be appropriate due to the intimate nature of the learning environment, supporting organizations dedicated to language preservation is invaluable. Learning about the specific languages of the lands you visit, seeking out cultural centers, museums, and events where Indigenous languages are spoken or celebrated, and purchasing authentic Indigenous arts and crafts from fluent speakers, are all ways to engage respectfully and meaningfully.

The map serves as a reminder that history is not static; it is a living process. The resilience embedded in each dot tells a story of overcoming immense adversity, of communities refusing to let their heritage fade. It’s a story of love for culture, respect for elders, and an unwavering commitment to the future. These Native American language immersion schools are not just educational institutions; they are sacred spaces where the whispers of ancestors are brought back to life, where the deepest meanings of identity are forged, and where the rich tapestry of Indigenous North America continues to weave itself, vibrant and strong, for generations to come. To understand this map is to understand a crucial, hopeful chapter in the ongoing narrative of Indigenous peoples.