The Unseen Map: Navigating Native American Land Rights, History, and Identity

Forget the neatly delineated borders on conventional maps. To truly understand the land beneath our feet in North America, we must unlearn and relearn, tracing an unseen map—one etched in centuries of Indigenous history, defined by complex land rights, and vibrant with enduring identity. This is not merely an academic exercise; it’s an essential journey for any traveler or student of history seeking to engage ethically and deeply with the continent’s past and present. This article will unpack the intricate layers of Native American land rights, exploring their historical evolution, profound connection to identity, and the ongoing struggles and triumphs that continue to shape Indigenous nations today.

Before the Borders: A Continent of Nations

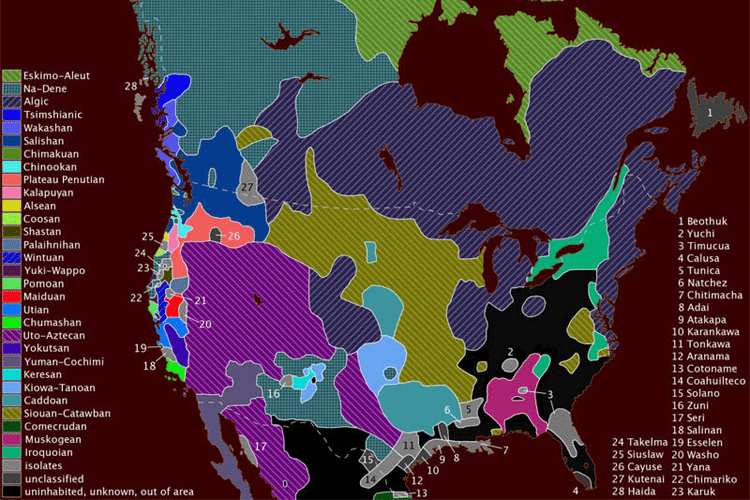

Before European contact, North America was not an empty wilderness but a mosaic of thriving, self-governing Indigenous nations, each with distinct languages, cultures, spiritual beliefs, and sophisticated systems of land stewardship. From the agricultural societies of the Mississippi Valley (like the Cahokia) to the nomadic hunters of the Great Plains (like the Lakota and Cheyenne), the coastal fishing communities of the Pacific Northwest (like the Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw), and the complex confederacies of the Northeast (like the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee), Indigenous peoples managed vast territories. Their understanding of land ownership was often communal, based on usufructuary rights—the right to use and benefit from land and its resources—rather than exclusive individual possession. Boundaries, while understood, were often permeable, reflecting alliances, trade routes, and shared resources. This pre-colonial map, vibrant with diversity and sustainable practices, is the essential starting point for understanding everything that followed.

The Doctrine of Discovery and the Seeds of Dispossession

The arrival of European colonizers marked a catastrophic turning point. Driven by imperial ambitions, religious zeal, and the insidious Doctrine of Discovery—a legal concept originating in the 15th century that asserted Christian nations had a right to claim lands inhabited by non-Christians—the newcomers systematically dispossessed Indigenous peoples. This was not a simple transaction but a brutal process of disease, warfare, forced removal, and broken promises. European powers, and later the United States, claimed sovereignty over vast territories, often ignoring or outright violating the pre-existing rights of Indigenous nations.

The nascent U.S. government, while often acknowledging Native American nations as sovereign entities capable of making treaties, simultaneously pursued policies aimed at land acquisition. Early treaties, theoretically agreements between sovereign nations, were frequently signed under duress, misinterpreted, or outright violated by the U.S. government. These initial land cessions, often exchanged for goods or promises of protection, chipped away at Indigenous territories, setting a dangerous precedent.

Manifest Destiny and the Era of Removal

The 19th century witnessed the full force of American expansionism, fueled by the ideology of Manifest Destiny—the belief that the United States was divinely ordained to expand across the North American continent. This era was particularly devastating for Native American land rights. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced displacement of thousands of Southeastern Indigenous peoples (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole) from their ancestral lands to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). The infamous "Trail of Tears," the forced march of the Cherokee Nation, resulted in the deaths of thousands and stands as a stark symbol of this brutal policy.

Even as some tribes resisted fiercely, like the Seminoles in Florida or the Lakota on the Great Plains, the overwhelming military and demographic power of the U.S. government led to further land loss. Battles like Sand Creek Massacre, Wounded Knee, and the sustained Plains Wars further solidified federal control, pushing tribes onto increasingly smaller, isolated parcels of land: reservations.

The Reservation System: A Paradox of Sovereignty

The reservation system, largely formalized by the mid-19th century, represents a deeply contradictory aspect of U.S. policy. These were not gifts but often the remnants of ancestral lands, ceded under duress, or newly designated territories where tribes were confined. The intent was often dual: to "civilize" Indigenous peoples by forcing them into agrarian lifestyles and to open vast tracts of land for white settlement.

Within these often-diminished boundaries, a complex form of "domestic dependent nation" status emerged, where tribes retained a degree of inherent sovereignty, yet remained under the ultimate plenary power of the federal government. This meant that while tribal governments could administer their own affairs, manage resources, and enforce laws within their reservations, their ultimate authority was subject to federal oversight and legislation.

This era also saw the implementation of the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887, a disastrous policy designed to break up communal tribal lands into individual allotments. The stated goal was to integrate Native Americans into mainstream society by turning them into individual farmers. In reality, it led to the loss of two-thirds of the remaining tribal land base—nearly 90 million acres—as "surplus" lands were sold off to non-Native settlers, and many Indigenous allottees were defrauded or unable to maintain their parcels. This policy severely fractured tribal communities and undermined traditional land tenure systems, further eroding the Native American land base.

Reclaiming Identity and Sovereignty: The 20th Century and Beyond

The early 20th century continued the trend of forced assimilation, with policies like mandatory boarding schools aiming to strip Indigenous children of their language, culture, and identity. However, the tide began to turn with the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, which, while still a federal initiative, reversed the Dawes Act’s allotment policy and encouraged tribes to adopt written constitutions and establish self-governance. While imperfect and often imposing foreign governance structures, the IRA marked a shift towards recognizing tribal sovereignty.

Yet, this was followed by another devastating policy: Termination. From the 1940s to the 1960s, the U.S. government sought to "terminate" its trust relationship with specific tribes, effectively ending their federal recognition, abolishing reservations, and dissolving treaty obligations. This policy was catastrophic for the affected tribes, leading to immense poverty and loss of services. Fortunately, the termination era was largely repudiated by the 1970s.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and 70s galvanized Native American activism. Organizations like the American Indian Movement (AIM) brought national attention to treaty violations, land claims, and issues of self-determination. Events like the occupation of Alcatraz (1969-71) and Wounded Knee (1973) highlighted the ongoing struggles for justice and sovereignty.

This period ushered in the "Self-Determination Era," marked by the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This landmark legislation empowered tribes to take control of federal programs and services designed for their communities, shifting away from direct federal administration. It enabled the resurgence of tribal governments, the development of tribal economies (including gaming, natural resource management, and tourism), and a renewed focus on cultural preservation and language revitalization.

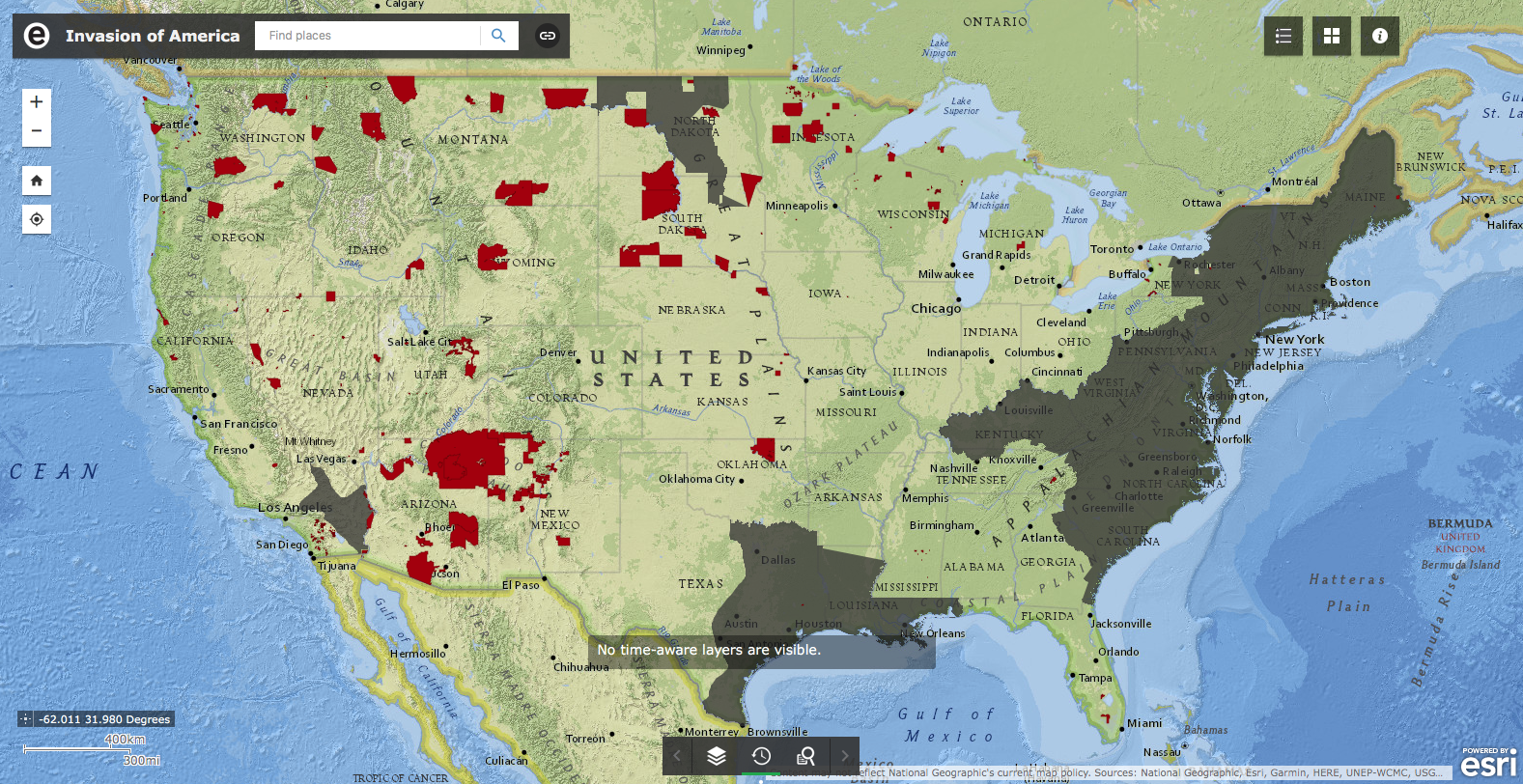

The Modern Map: A Patchwork of Rights and Realities

Today, the map of Native American land rights is a complex, dynamic patchwork. There are over 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States, each with a unique government-to-government relationship with the U.S. federal government. These tribes collectively manage over 56 million acres of land, primarily held in trust by the federal government for the benefit of the tribes and their members. This trust status means the federal government has a fiduciary responsibility to protect tribal lands and resources.

However, "Indian Country" is not monolithic. It includes:

- Reservations: Lands set aside for tribes, often with complex jurisdictional issues involving tribal, state, and federal law.

- Trust Lands: Lands held in trust by the U.S. government for individual Native Americans or tribes, which may or may not be part of a formal reservation.

- Allotments: Individual parcels of land originally distributed under the Dawes Act, often resulting in "checkerboarding" of ownership, where tribal, individual Native, and non-Native lands are interspersed, creating administrative and legal challenges.

- Ancestral Lands: Territories historically occupied by tribes, much of which is no longer under tribal control but remains culturally and spiritually significant.

- Sacred Sites: Places of profound spiritual importance, often located outside current reservation boundaries, where tribes continue to advocate for protection and access (e.g., Bears Ears National Monument, Black Hills).

Ongoing legal battles frequently involve water rights, mineral rights, land claims, and jurisdictional disputes. Tribes continually assert their inherent sovereignty, seeking to strengthen their self-governance, protect their natural resources, and preserve their cultural heritage against external pressures.

Identity Beyond Borders: Land, Culture, and Future

For Native Americans, the connection to land transcends mere ownership; it is foundational to identity, spirituality, and cultural survival. The land is not just soil and resources; it is a repository of history, the burial ground of ancestors, the source of traditional foods and medicines, and the classroom for future generations. Language, ceremonies, traditional stories, and kinship systems are all deeply interwoven with specific landscapes.

Despite centuries of dispossession and forced assimilation, Native American identity has proven remarkably resilient. Today, Indigenous nations are vibrant, diverse, and forward-looking. They are leading efforts in environmental protection, sustainable development, cultural revitalization, and advocating for social justice on both national and international stages. Their identity is not a relic of the past but a living, evolving force, rooted in ancestral knowledge and adapting to contemporary challenges.

For the Traveler and Learner: Ethical Engagement

For those exploring the landscapes of North America, understanding this complex map of Native American land rights, history, and identity is not just respectful; it’s essential for a deeper, more meaningful experience.

- Acknowledge the Land: Before visiting any area, learn about the Indigenous peoples who are the original stewards of that land. Many organizations and institutions now offer land acknowledgments as a practice of respect.

- Educate Yourself: Move beyond stereotypes. Seek out authentic Indigenous voices—books, documentaries, podcasts, and online resources from tribal nations themselves.

- Visit with Respect: If you visit a reservation or tribal cultural center, do so with an open mind and a respectful attitude. Understand that you are a guest on sovereign land. Learn about local customs, ask for permission before photographing people or ceremonies, and respect sacred sites.

- Support Tribal Economies: Whenever possible, support Indigenous-owned businesses, artists, and tourism initiatives. This directly benefits tribal communities and fosters self-determination.

- Understand Ongoing Issues: Recognize that the struggles for land rights, sovereignty, and justice are not relegated to the past. They are ongoing. Engage with current events and learn about contemporary Indigenous activism.

Conclusion

The map of Native American land rights is a living document, constantly being redrawn through legal battles, political advocacy, and cultural revitalization. It is a testament to both profound injustice and extraordinary resilience. By understanding its intricate contours, we not only honor the past and present of Indigenous peoples but also gain a more complete, truthful, and nuanced understanding of the continent we inhabit. This unseen map is not just about land; it’s about justice, sovereignty, and the enduring spirit of nations who continue to call this land home.