>

The Unseen Landscape: Reading the Map of Native American Land Dispossession

Maps are more than mere guides to geography; they are narratives etched in lines and colors, telling stories of power, change, and often, profound loss. For Native Americans, a map of their ancestral lands reveals not just ancient territories but a devastating chronicle of dispossession—a story that is central to understanding the very fabric of the United States. This isn’t just a historical artifact; it’s a living document of resilience, identity, and an ongoing struggle for justice that every traveler and history enthusiast should comprehend.

A Continent of Nations: The Pre-Colonial Tapestry

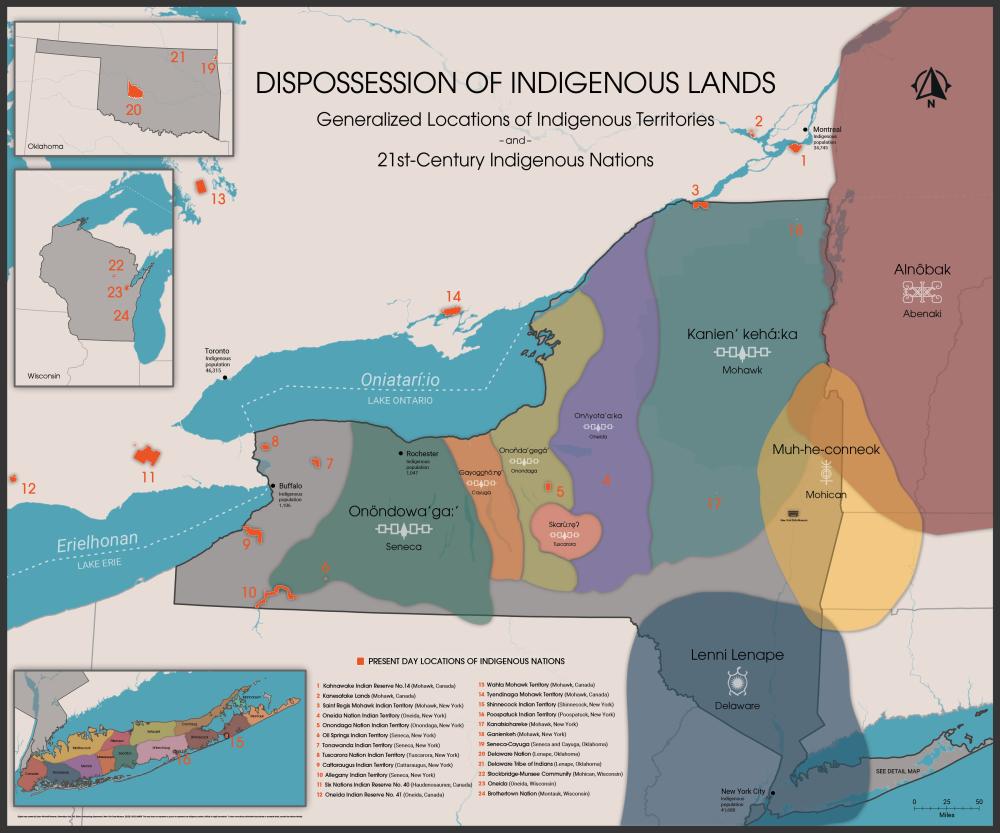

Before the arrival of Europeans, North America was a vibrant, complex mosaic of hundreds of distinct Native nations, each with its own language, culture, governance, and deep spiritual connection to specific lands. From the vast buffalo hunting grounds of the Lakota and Cheyenne on the Great Plains to the intricate agricultural societies of the Haudenosaunee in the Northeast, the fishing villages of the Coast Salish in the Pacific Northwest, and the desert communities of the Diné (Navajo) and Hopi in the Southwest, these lands were not "empty wilderness." They were meticulously managed, intimately understood, and sustained by generations of Indigenous peoples.

A map of pre-colonial America would show fluid, overlapping territories, defined by resource use, cultural ties, and intricate trade networks rather than rigid, colonial-style borders. Rivers, mountains, and forests were not obstacles but integral parts of identity, sacred sites, and pathways for connection. This profound relationship with the land—where identity, spirituality, and survival were inextricably linked—forms the essential backdrop against which the story of dispossession unfolds.

The Tide Turns: Early European Encroachment and the Doctrine of Discovery

The arrival of European colonists—Spanish, French, British, and Dutch—marked the beginning of an epochal shift. Initial interactions were varied, ranging from cautious trade to immediate conflict. However, underlying European expansion was the "Doctrine of Discovery," a legal and religious concept originating in 15th-century papal bulls. This doctrine asserted that Christian European nations had the right to claim land inhabited by non-Christians, effectively denying the inherent sovereignty and land rights of Indigenous peoples.

Early colonial maps began to reflect this new reality, overlaying European claims onto existing Native territories. As settlements grew, particularly along the East Coast, Native nations like the Wampanoag, Powhatan, and Narragansett faced mounting pressure. Treaties were often signed under duress, misunderstood due to language and cultural barriers, or simply violated by colonists hungry for land. Wars, fueled by disease and technological disparity, further decimated Native populations and led to significant land cessions. By the late 18th century, with the birth of the United States, the eastern seaboard was largely under colonial control, pushing many surviving Native communities westward or onto smaller, designated tracts.

Manifest Destiny and the Era of Forced Removal (19th Century)

The 19th century saw the United States rapidly expand its borders, driven by the ideology of "Manifest Destiny"—the belief in America’s divine right to expand across the continent. This expansion came at an unimaginable cost to Native nations.

The Indian Removal Act (1830): This landmark legislation, championed by President Andrew Jackson, authorized the forced removal of Native American tribes from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to territories west of the Mississippi River. Tribes like the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole, many of whom had adopted elements of American culture, developed writing systems, and established constitutional governments, were forcibly uprooted. The most infamous consequence was the "Trail of Tears," where thousands of Cherokee perished from disease, starvation, and exposure during their forced march in the winter of 1838-39. This act dramatically redrew the map, shrinking once-vast Native territories into smaller, often undesirable "Indian Territory."

The Treaty System (and its failures): Throughout the 19th century, the U.S. government engaged in hundreds of treaties with Native nations, ostensibly to define boundaries and ensure peace. However, these treaties were routinely broken, reinterpreted, or signed under duress, often with unrepresentative leaders. Each broken treaty meant more land ceded, more communities displaced, and a further erosion of Native sovereignty. A map charting these treaties would show a relentless westward march of U.S. claims, systematically shrinking Native landholdings.

The Plains Wars: As settlers pushed onto the Great Plains, conflict erupted with powerful nomadic tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Comanche, whose way of life was inextricably linked to the buffalo and vast hunting grounds. The U.S. military engaged in brutal campaigns, culminating in massacres like Wounded Knee (1890). The decimation of the buffalo herds, a deliberate tactic, further undermined Native self-sufficiency and forced tribes onto reservations.

The Reservation System and Assimilation Policies

By the late 19th century, the era of widespread removals gave way to the policy of "concentration" on reservations. Reservations were tracts of land, often marginal and far smaller than original territories, set aside for specific tribes. While sometimes framed as protective measures, they were largely designed to contain, control, and "civilize" Native peoples.

The Dawes Act (General Allotment Act of 1887): This was perhaps the most devastating piece of legislation in terms of land loss within the reservation system. The Dawes Act aimed to break up communally held tribal lands into individual allotments (typically 160 acres) for Native families. The "surplus" land—often millions of acres—was then declared open for sale to non-Native settlers. This policy was a direct assault on Native communal land ownership, a cornerstone of many tribal identities and economies. It resulted in the loss of two-thirds of the remaining Native American land base between 1887 and 1934, further fragmenting tribal communities and eroding their self-sufficiency. A map of reservations after the Dawes Act would show them riddled with non-Native ownership, creating a "checkerboard" pattern of jurisdiction and ownership challenges that persist today.

Boarding Schools: Concurrent with land dispossession were aggressive assimilation policies, most notably the forced enrollment of Native children in off-reservation boarding schools. The motto "Kill the Indian, Save the Man" encapsulated the goal: to strip children of their language, culture, spiritual practices, and connection to their families and land. This cultural genocide, though not directly about land, aimed to sever the intergenerational transmission of identity that was deeply tied to place and tradition.

The 20th Century and Beyond: Resistance, Resilience, and Reclamation

The mid-20th century brought some policy shifts. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 ended the Dawes Act’s allotment policy and encouraged tribal self-governance. However, this was followed by the disastrous Termination Policy (1950s-1960s), which aimed to dissolve tribes as legal entities, leading to further land loss and economic hardship for many.

The Self-Determination Era, beginning in the 1970s, marked a significant turning point. Native nations began to assert their sovereignty more forcefully, taking control of their own education, healthcare, and economic development. Legal battles for treaty rights, land claims, and water rights became increasingly common.

Today’s map of Native American lands shows a fragmented landscape: approximately 326 federally recognized reservations and trust lands, representing a mere 2.3% of the U.S. landmass. These lands are often geographically isolated, economically challenged, but are also vibrant centers of cultural revitalization and self-governance. Many tribes are actively engaged in land acquisition, environmental protection, and cultural preservation efforts, often referred to as the "Land Back" movement. This includes efforts to restore sacred sites, protect ancestral burial grounds, and re-establish traditional land management practices.

History and Identity: The Enduring Legacy

The map of Native American land dispossession is more than a historical record; it is a profound narrative of identity. For Native peoples, land is not merely property; it is a source of spiritual power, cultural knowledge, language, and ancestral memory. The forced removal from these lands, the destruction of ecosystems, and the suppression of traditional practices have inflicted intergenerational trauma, impacting health, economy, and social well-being.

Yet, this map also tells a story of extraordinary resilience. Despite centuries of systemic attempts to erase their cultures and seize their lands, Native nations have survived. Their identities, though deeply scarred by dispossession, remain vibrant, dynamic, and inextricably linked to their ancestral territories, even those they no longer physically control. Language revitalization programs, ceremonial practices, traditional arts, and political advocacy are all expressions of this enduring connection to land and identity.

Conclusion: Why This Map Matters Today

For travelers and those seeking a deeper understanding of American history, engaging with the map of Native American land dispossession is essential. It challenges the romanticized narratives of westward expansion and reveals the often-unacknowledged foundations of modern American wealth and power.

Understanding this map means:

- Recognizing the true cost of colonization: It helps us acknowledge the immense suffering and loss endured by Indigenous peoples.

- Appreciating Native resilience: It highlights the incredible strength, adaptability, and determination of Native nations to maintain their cultures and identities.

- Supporting Native sovereignty: It underscores the ongoing importance of respecting tribal governments and their rights to self-determination.

- Informing responsible tourism: It encourages visitors to approach Native lands and communities with respect, to seek out Indigenous-led tours, support Native businesses, and learn about the local tribal history of the places they visit.

The "Map of Native American Land Dispossession" is not a static relic of the past. It is a dynamic, living testament to a complex history that continues to shape the present. By truly seeing and understanding this map, we can begin to walk a more informed, empathetic, and ultimately, more just path forward.