The "Map of Native American land back movement" is not merely a cartographic exercise; it is a profound declaration of sovereignty, a visual testament to historical injustice, and a powerful blueprint for a decolonized future. Far from being a simple drawing, it represents a complex, deeply rooted movement advocating for the return of ancestral lands to Indigenous peoples across North America. For anyone interested in travel, history, or social justice, understanding this map and the movement it embodies is essential to truly grasping the continent’s past, present, and potential future.

The Great Taking: A History of Dispossession

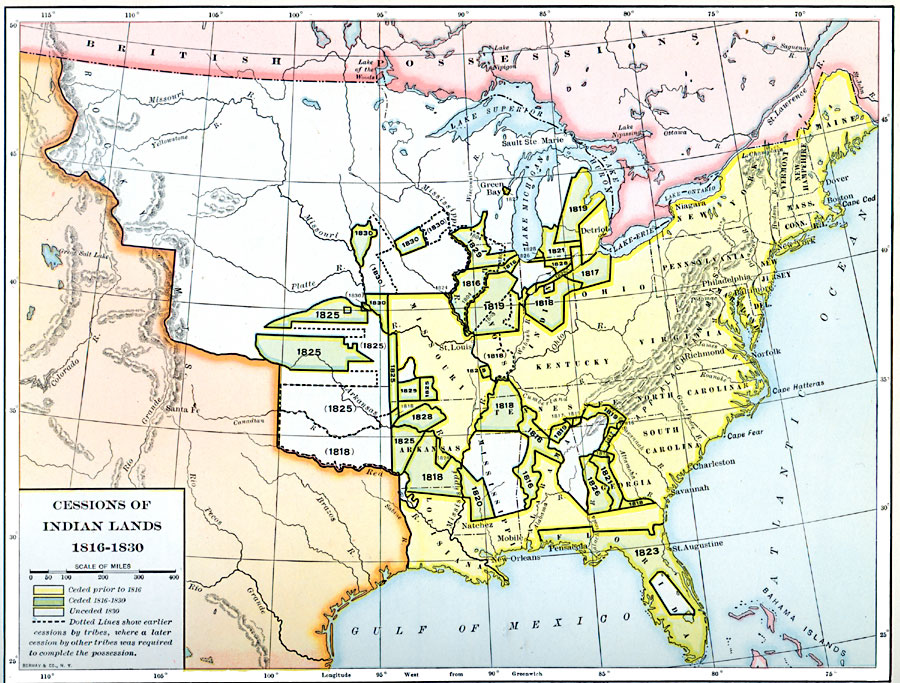

To understand the "land back map," one must first confront the history of land dispossession that defines much of the North American continent. Before European contact, Indigenous nations thrived across vast territories, each with distinct cultures, languages, governance systems, and intricate relationships with their lands. These lands were not merely resources; they were integral to identity, spirituality, economic sustenance, and social structure. The arrival of European settlers, however, initiated a centuries-long process of colonization built upon the Doctrine of Discovery – a legal concept originating in the 15th century that asserted European Christian nations had the right to claim lands inhabited by non-Christians.

This doctrine paved the way for a systematic campaign of land theft, often under the guise of treaties that were routinely broken, misinterpreted, or coerced. The United States, in particular, pursued an aggressive policy of westward expansion, leading to devastating wars, forced removals, and the concentration of Indigenous peoples onto increasingly smaller, often undesirable, reservations. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, for instance, led to the infamous Trail of Tears, forcibly displacing the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations from their ancestral lands in the southeastern United States to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). Millions of acres were seized, cultures were disrupted, and entire ways of life were threatened.

Even the establishment of reservations, initially conceived as permanent homes, proved to be temporary safeguards against further land loss. The Dawes Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act) aimed to break up tribal communal landholdings into individual parcels, with the "surplus" land then sold off to non-Native settlers. This policy resulted in the loss of two-thirds of the remaining Indigenous land base – approximately 90 million acres – between 1887 and 1934. Later, 20th-century policies like "termination" sought to dissolve tribal governments and assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream society, further eroding their land base and sovereignty. This relentless historical trajectory of land loss forms the bedrock upon which the Land Back movement stands, challenging the legitimacy of current land ownership and demanding a reckoning with historical wrongs.

Unveiling the "Land Back Map": A Visual Call to Justice

So, what exactly is the "Map of Native American land back movement"? It is not a single, universally agreed-upon cartographic document but rather a conceptual framework, often materialized through various mapping projects, digital interfaces, and grassroots visualizations. At its core, it is a visual representation of:

- Ancestral Territories: It overlays modern political boundaries (states, counties, national parks) with the original, unceded, or illegally seized territories of hundreds of distinct Indigenous nations. This immediately reveals the vast disparity between current Indigenous landholdings (primarily reservations) and the lands historically occupied and stewarded.

- Challenging Settler Narratives: By highlighting ancestral lands, these maps directly challenge the narrative of terra nullius (empty land) or "discovery" that underpinned colonial expansion. They assert the continuous presence and inherent sovereignty of Indigenous peoples.

- Educational Tool: The maps serve as powerful educational tools, illustrating the scale of land theft and the diversity of Indigenous nations, many of which are often invisible in mainstream education. They show that "America" is built upon Indigenous land, and that every square inch has a Native history.

- Advocacy and Organizing: For the Land Back movement itself, these maps are crucial for organizing, identifying priority areas for reclamation, and educating non-Native allies on the scope of the demands. They make the abstract concept of "stolen land" tangible and geographically specific.

- Diverse Claims: Crucially, these maps illustrate the diversity of Indigenous claims. Some claims are based on treaty violations, others on unceded territories, and still others on the return of sacred sites or culturally significant areas. The map is not monolithic; it reflects the unique histories and aspirations of hundreds of distinct nations.

Imagine a map where Yellowstone National Park is identified as part of the ancestral territory of the Shoshone, Crow, Bannock, and Blackfeet peoples, or where downtown Los Angeles is recognized as the traditional homeland of the Tongva. These maps force viewers to confront the Indigenous history beneath their feet, prompting questions about who truly belongs to the land and what justice looks like.

More Than Land: Identity, Sovereignty, and Healing

The Land Back movement is not solely about property disputes or lines on a map; it is fundamentally about the revitalization of Indigenous identity, the restoration of sovereignty, and the healing of historical trauma. For Indigenous peoples, land is not merely a commodity; it is a living entity, a source of spiritual power, cultural knowledge, and community well-being.

- Identity and Culture: Traditional languages, ceremonies, stories, and subsistence practices are often inextricably linked to specific landscapes. The loss of land has meant the erosion of these cultural pillars. Land Back seeks to restore the physical spaces necessary for cultural revitalization, allowing Indigenous peoples to practice their traditions freely and transmit them to future generations. Reconnecting with ancestral lands allows for the re-establishment of relationships that define who they are.

- Sovereignty and Self-Determination: True sovereignty means the right to govern oneself and make decisions about one’s future. For many Indigenous nations, the ability to control and manage their ancestral lands is paramount to exercising this self-determination. Land Back is about reclaiming decision-making power over resources, environmental stewardship, economic development, and cultural preservation, independent of colonial governments. It’s about having the authority to determine what happens on one’s own territory.

- Environmental Stewardship: Indigenous peoples have practiced sustainable land management for millennia, developing intricate traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) that prioritizes balance and long-term health. As the world faces a climate crisis, the Land Back movement offers a powerful solution. Returning land to Indigenous stewardship could lead to more effective conservation, climate resilience, and sustainable resource management, benefiting all inhabitants of the continent. Their deep understanding of local ecosystems, passed down through generations, represents an invaluable asset for planetary health.

- Economic Justice: Decades of land dispossession have led to economic marginalization and poverty for many Indigenous communities. Reclaiming land can provide a foundation for sustainable economic development rooted in traditional values, such as eco-tourism, traditional agriculture, sustainable forestry, and renewable energy projects, breaking cycles of dependency.

- Healing and Reconciliation: For many, Land Back is a critical component of reconciliation – acknowledging past injustices and actively working to repair their harms. It represents a step towards collective healing, not just for Indigenous communities, but for the entire society grappling with its colonial past. It is an opportunity to build new relationships based on respect, equity, and mutual benefit.

The Path Forward: Challenges and Opportunities

The "Land Back map" presents a vision, but the path to achieving it is complex and multifaceted. It’s important to clarify what Land Back often entails: it’s not always about immediately displacing non-Native residents from their homes. Instead, it encompasses a spectrum of actions:

- Return of Public Lands: A significant focus is on the return of federal, state, and provincial lands (national parks, forests, military bases) that sit on unceded Indigenous territories. Examples include efforts to return portions of national parks to tribal co-management or full ownership. The recent designation of Bears Ears National Monument, with significant tribal input, is one such step.

- Co-Management Agreements: Partnering with Indigenous nations to co-manage lands and resources, ensuring Indigenous perspectives and traditional ecological knowledge are central to decision-making.

- Reparations and Restitution: Financial compensation or other forms of restitution for past land theft and its ongoing impacts.

- Legal and Legislative Reforms: Challenging existing property laws, enforcing treaty rights, and enacting new legislation that facilitates land return.

- Private Land Buy-Backs and Donations: Grassroots efforts to purchase private lands for return to Indigenous communities, or donations from non-Native landowners.

- Urban Land Initiatives: Reclaiming and revitalizing Indigenous spaces within urban areas for cultural centers, housing, and community gardens.

The challenges are significant: legal hurdles, political resistance, financial constraints, and public education are all ongoing battles. However, the opportunities for a more just, sustainable, and respectful future are immense.

For Travelers and Educators: A Call to Awareness

For those who travel and seek to understand the world, the "Map of Native American land back movement" offers an invaluable lens. When you visit a national park, hike a scenic trail, or explore a historic town, consider whose ancestral lands you are on. Seek out Indigenous-led tourism initiatives, support Indigenous businesses, and learn about the local Indigenous history from Indigenous voices. Engage with the ongoing narratives of sovereignty and resilience.

For educators, incorporating this understanding into curricula is vital. Moving beyond superficial lessons on "first Thanksgiving" or "tipis and canoes," and instead teaching the complex history of Indigenous nations, the impact of colonization, and the ongoing struggles for justice, is crucial. The Land Back map provides a tangible way to make these histories visible and relevant.

In conclusion, the "Map of Native American land back movement" is far more than just geography; it is a powerful symbol of decolonization, a call for justice, and a vision for a future where Indigenous sovereignty, culture, and environmental stewardship are honored and restored. It challenges us all to re-examine our relationship with the land, understand the true cost of history, and actively participate in building a more equitable and sustainable world for all. By engaging with this map, we engage with a profound truth that has long been suppressed: the land remembers, and its original caretakers are calling for its return.